- September 18, 2024

- By Sala Levin ’10

Twenty-two-year-old A hated that they’d had to start wearing a bra earlier than classmates and desperately wanted to be flat-chested. As a teen, while watching a show on weight loss, they saw a man wrap himself in plastic wrap to sweat off a few pounds—and thought, “What if I shrink-wrapped my chest?” The flaw in this plan quickly became apparent: They couldn’t breathe.

This anecdote came from a participant in a research project by Sarah Peitzmeier ’10 at the University of Michigan, where she was an assistant professor of health behavior and biological sciences. She and her collaborators tracked 25 people who bind their chests for three months, collecting daily data on their mental health, side effects of the practice and quality of life.

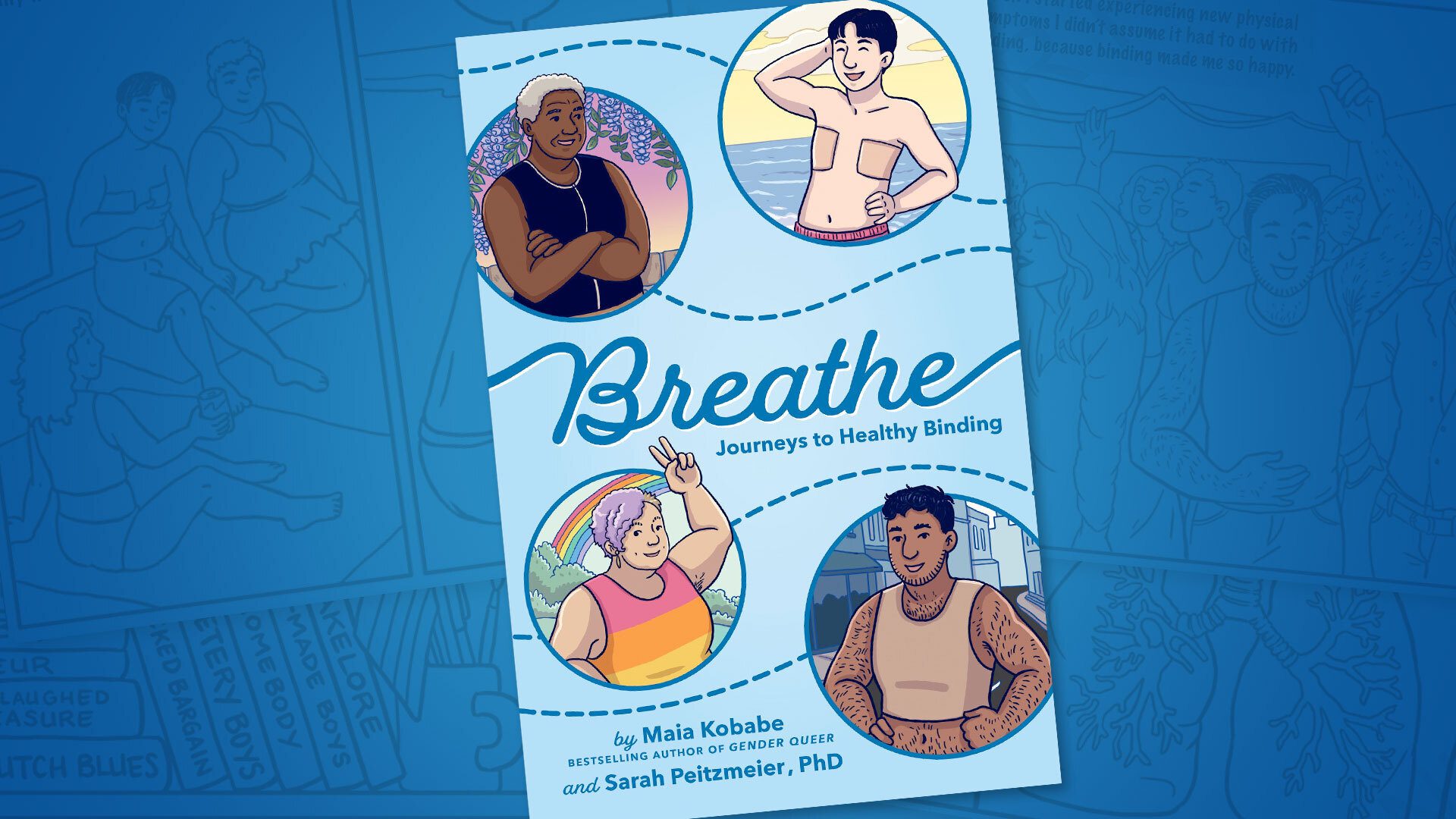

The result is “Breathe: Journeys to Healthy Binding,” a graphic novel that explores why people bind and how to do it safely. Released by Penguin Random House in May, the comic book is a frank examination of this “really life-changing, and sometimes lifesaving, practice for folks in the trans community,” said Peitzmeier, who joined the University of Maryland in August as an assistant professor of behavioral and community health.

“Chest binding” refers to any intentional flattening of breasts, and its history is long and varied. In imperial China, upper-class women would wear a garment known as a dudou to conceal their breasts’ curves, and in America in the 1920s, some women compressed their chests to achieve the boyish body popularized by flappers.

Today, chest binding is most common among people with breasts who want to defeminize their appearance. After publishing about the practice in academic journals, Peitzmeier found herself getting emails from trans teenagers, their parents and their teachers who wanted to learn from her work but lacked access to her research. She thought, “What’s the point of doing this work if the communities who could benefit from it, can’t?” So she began writing “Breathe” alongside Kobabe, author of the graphic memoir “Gender Queer,” which has topped the American Library Association’s list of “challenged books” for three years in a row. (Peitzmeier said response to “Breathe” has so far been positive, but she expects the books to be banned in some places.)

Here are four things Peitzmeier says people should know about chest binding.

- Binding can be a lifeline. “People report reductions in depression, anxiety, even suicidality from being able to bind, because it makes such a difference in how they’re able to present themselves to the world,” she said. Especially in the 26 states that now restrict medical treatment for young people who want to transition, binding may be the only way for adolescents to safely affirm their gender, she added.

- Chest binding is a simple way to experiment with gender presentation. The practice is an easy access point for people of any age who are questioning their gender identity, said Peitzmeier. “It’s often an early step people take to affirm their gender and see if that is a positive change in their life.”

Binding doesn’t make any permanent changes to the body and is fairly affordable: Many commercially made garments for binding are available for less than $60, as well as tape made specifically for the practice; people also often create DIY versions by layering sports bras or tight camisoles.

- Elastic bandages aren’t a safe binding option. They can compress the wearer’s chest too tightly, said Peitzmeier, potentially leading to lung or rib issues. “If you’re binding too tightly, you can get really out of breath. People can get dizzy and faint.” In rare cases, people wearing elastic bandages have experienced rib fractures, she said. Plus, if you’re wearing a too-tight binder in public and start feeling lightheaded, finding a nearby spot to discreetly remove the binder can be a challenge.

A binder wearer who is regularly experiencing pain might want to consider going up a size or taking one day off a week from the practice. “Pay attention to those signals your body is sending you and try something different,” said Peitzmeier.

- If your child approaches you wanting to learn more about chest binding, take it as a sign of trust. “First of all, kudos to you, because your child felt safe to talk with you about what’s going on in their life,” she said. Listening to your child and understanding what they hope to achieve by chest binding is key to a successful outcome. “Read up on your research to help guide your child, maintain an open dialogue, and if there are any negative side effects coming up, talk to their doctor.”

Topics

ResearchUnits

School of Public Health