- March 05, 2025

- By Karen Shih ’09

Maybe you’ve always wanted to add a buff Pikachu to your action figure collection. Or to piece together a topographically accurate 2-foot-wide globe. Or to replicate your canine companion—sized to fit in the palm of your hand.

It’s all possible at the Advanced Fabrication Lab, the flagship facility of Terrapin Works, a unit of the A. James Clark School of Engineering that provides design, education and manufacturing services to the University of Maryland community and beyond. Inside the lab on the second floor of A. James Clark Hall, you’re surrounded by the constant whirring and clicking of dozens of 3D printers and other complicated machinery, bins of colorful plastic scraps and plenty of student workers who are eager to help.

Operations Manager Evan Hutzell ’20 is one of six full-time employees and about 90 student workers, who range from entry-level technicians to machine specialists. Cranking out about 2,200 projects per year, mostly for Clark School faculty, staff and students, Terrapin Works serves a client base that’s fairly evenly split between students and researchers, while about 10% come from off campus.

“It’s amazing the amount of technology we have access to here. A lot of it is insanely expensive, and you never get to see it anywhere else. It’s mind-boggling,” said Adam Brodsky ’26, a fire protection engineering major who serves as a technical supervisor. “It's just really exciting to be able to take an idea and just make it an actual thing.”

Hutzell and Brodsky explain how they create mini versions of campus’ most iconic statues, how plastic is just one of the many materials they can 3D-print and some of the most unusual projects they’ve worked on.

Scanning and Designing

It’s not quite “Honey, I

Shrunk the Kids,” but the collection of 4-inch-tall Frederick

Douglasses, bronze Testudos (5,000 of them given to incoming freshmen

last year) and even a Greg Heffley (star of Jeff Kinney ’96’s “Wimpy

Kid” books) offer a glimpse at what UMD could look like in miniature. To

make these, the Terrapin Works team starts with a scan.

There’s an in-lab arm for smaller items, and a portable one that can be taken out to use in the field. “People love to scan people,” said Brodsky (many a fellow student worker has been immortalized this way), as well as animals like crabs and dogs.

Most projects, however, start with a design created CAD software, like SolidWorks or Fusion360. Customers may find an existing design online, create one of their own (like students assigned to build the lightest bridge that can hold the most weight) or seek out the help of Terrapin Works’ design manager, Lauren Rathman.

A Material World

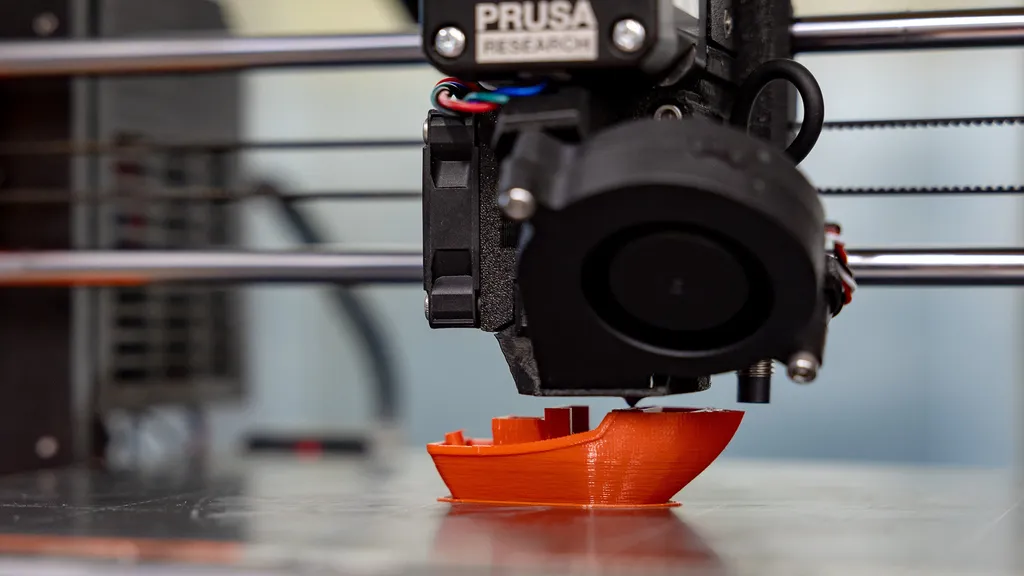

Plastic: About half of all Terrapin Works orders go through the “Fab Farm” (for “fabrication”), which features 22 printers.

“This is the cheapest, easiest type of printing,” said Hutzell. “These are the types that people have at home. If you don’t need super high-definition, you’re probably going to go here.”

The machines use spools of plastic filament in an array of colors, which they push through a heated nozzle to develop layers, eventually forming the object. Different filaments have different densities, so users can choose whether they need a lighter or heavier creation. This type of printing tends to leave rough edges and evident layers.

For clients with more stringent requirements, such as the Terps Racing team,

several other filament printers can incorporate stronger materials such

as Kevlar and carbon fiber. The AFL also has a powder-based inkjet

machine that can print colorful, chemical- and heat-resistant objects.

Resin: The faint glow emanating from the orange machines is a UV light, which cures the photopolymer resin for “more high-precision printing, if you want a really smooth surface,” said Brodsky. A more expensive material than plastic, resin can also be more rigid or flexible, depending on the customer’s needs.

Metal: These 3D printers use metal powder, combined with a binder, then go into an oven to finalize the creation of objects of materials like aluminum, titanium and stainless steel.

“Working with metal is much more complex,” said Brodsky. “You have to wear an entire suit with a respirator mask.”

Metal powder is expensive, so the AFL team batches orders to ensure they’re using the materials most efficiently, leading to longer wait times. In addition, objects can warp in the oven, so they don’t always turn out exactly as planned. These limitations mean they don’t currently get many metal orders—they have some chainmail on display and have had “good success” with rings—but Hutzell and his team are working to address these challenges.

Laser cutting: While most of the AFL’s gadgets build something up, one of them does the opposite, by cutting things out. The huge subtracted manufacturing machines can cut everything from plywood to steel and acrylic (some materials, like PVC, can’t be cut because they give off dangerous gasses like chlorine).

Engraving is also popular, said Brodsky. “For the Frederick Douglass statues, we made little bases and then engraved the whole logo.”

Failures and Favorites

Other than weaponry, like a taser glove the team once had to stop one user from making, there are few limits on what people can create through Terrapin Works.

“Somewhere around here, there’s an octopus with the Rock’s head on it,” said Brodsky. Hutzell himself got his start as a student worker because he wanted to make mini figurines for a Dungeons and Dragons campaign.

With customers bringing in their own designs, some, like the “giant blocky flip-flops” one guy wanted to print, were just that: a flop. “They were super uncomfortable,” said Brodsky.

On the flip side, Brodsky loved working with an art history professor who was recreating an ancient loom. He helped scan and design a mold that the faculty member used to form dimensionally accurate clay weights.

Other favorites include a laser-cut puzzle kit of the parts of an oyster for a Chesapeake Bay-focused organization and a reed-making device for a professor in the School of Music, all brought to life by Design Manager Lauren Rathmann with assistance from Naveen Anil.

Between customer orders, the team is always experimenting with the machines to see how they can improve and what new services they can offer. “It’s really exciting when you see a customer’s face light up” when they get their creation, said Brodsky.

This is part of a series that looks behind the scenes at “what it takes” to keep the University of Maryland humming and create a vibrant campus experience. Got an idea for a future installment? Email kshih@umd.edu.