- April 14, 2025

- By John Tucker

Glaucoma is a progressive, irreversible disease—the second-leading cause of blindness worldwide. It affects about 3 million Americans, yet half don’t know they have it until they start losing their sight.

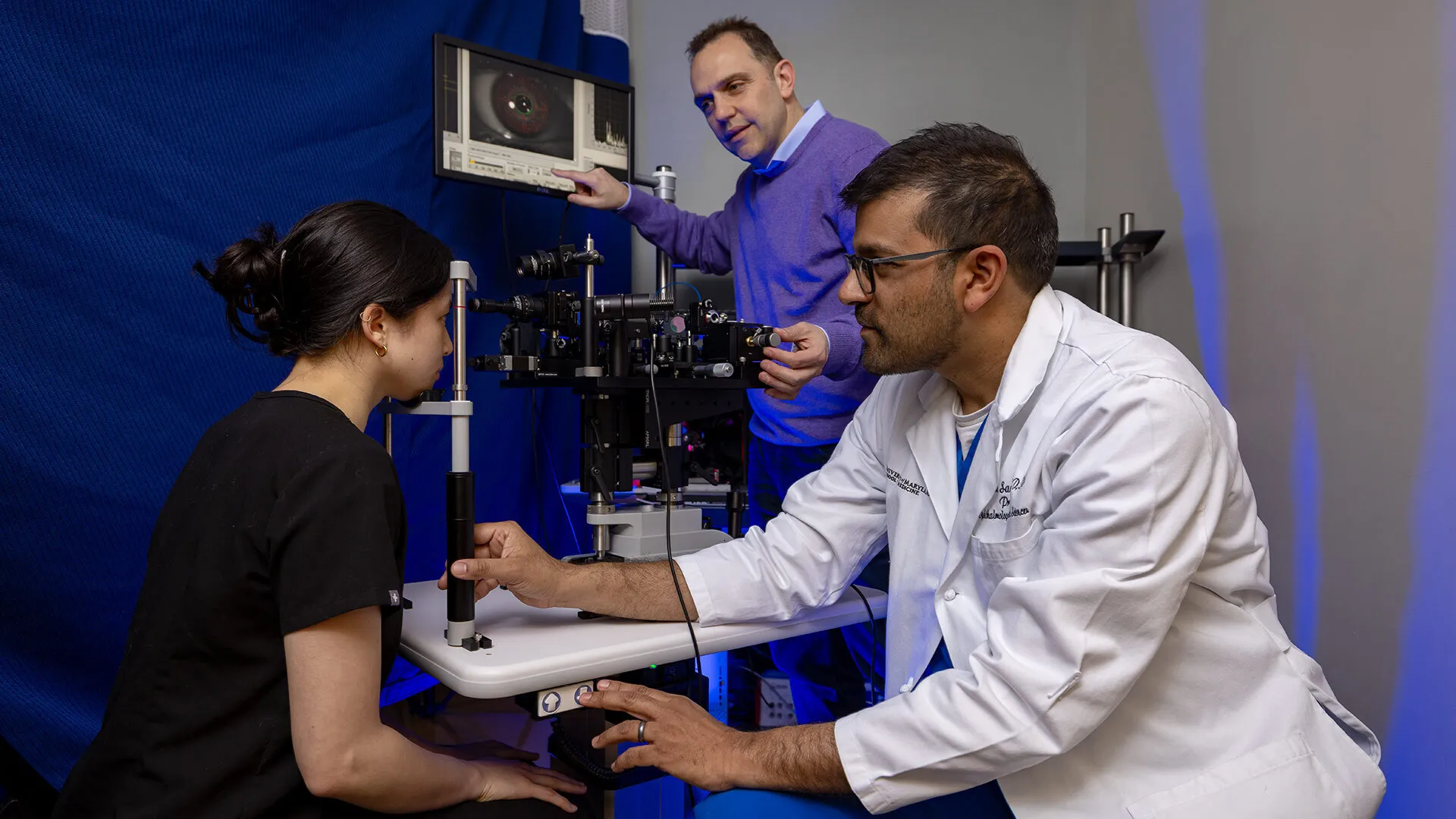

Giuliano Scarcelli, a University of Maryland associate professor of bioengineering, has spent his 20-year career building novel microscopes that detect early stages of corneal disease, helping patients ward off the need for surgery or even transplant. Now he is using his technology to explore the causes of glaucoma, hoping to spur development of new treatments. This month he is debuting his newest microscope, which will be tested with patients being treated at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM).

Scarcelli is one of two inaugural co-directors of the new Edward & Jennifer St. John Center for Translational Engineering and Medicine, an initiative fostering face-to-face partnerships among researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB), which houses UMSOM, and the A. James Clark School of Engineering at the University of Maryland, College Park (UMCP). The center, announced in January, is funded with a $10 million gift from the St. Johns and the Edward St. John Foundation, along with a $12.75 million grant from the University of Maryland Strategic Partnership: MPowering the State.

Scarcelli’s microscopes rely on Brillouin microscopy, a light-scattering technique that measures the stiffness of tissues and cells without touching the body—in this case the eye. The device can detect the tiniest natural vibrations within an eye’s tissue, providing information about its mechanical properties.

Unlike corneal disease, which manifests in the front of the eye, glaucoma patients suffer damage to the optic nerve, which is the nerve that connects each eye to the brain. Though elevated pressure is a common driver, the range of causes isn’t known. Unveiled last month, Scarcelli’s newest microscope is designed to determine eye stiffness, which might be a contributing factor.

“It’s expected that the pressure readings in a glaucoma patient are highly affected by how soft their cornea is,” Scarcelli said, likening an eye to an air balloon: If it’s softer in one area, it’s easier to push on it, regardless of its internal pressure.

Dr. Osamah J. Saeedi, an expert in the disease and professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at UMSOM—who joins Scarcelli as co-director of the St. John Center for Translational Engineering and Medicine—is betting that the new microscope can successfully be applied to his patients, some of whom don’t exhibit high eye pressure at all.

“For glaucoma, there’s been a real need to determine the basic biomechanics of the eye,” he said. “We want to find a way to do it noninvasively, and with Giuliano’s technique there is vast potential.”

Supported by a National Institutes of Health grant, Saeedi aims to identify once-elusive biomarkers of glaucoma among his patients, identify risks and develop personalized treatments by exploring mechanical variations within the eye.

Scarcelli built his first microscopes in 2006 as a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Medical School, supplying them to Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital to identify corneal diseases at early stages, before joining the UMD faculty in 2015.

Until recently, measuring an eye’s biomechanics has required applying force on the cornea, which inherently biases the measurement. Scarcelli’s contactless device eliminates this issue.

This summer, Scarcelli will take on a different kind of challenge: using Brillouin microscopy in Baltimore to measure biomechanics beyond the eye, an endeavor he outlined in a paper published last year in Nature Reviews. In his new lab at UMB, he will attempt to measure the stiffness of everything from blood to cancer cells to better understand the disease’s progression. The lab will be staffed with several postdoctoral fellows and doctoral students.

The Center for Translational Engineering and Medicine occupies the entire fourth floor of 4MLK, a new state-of-the-art facility in the University of Maryland BioPark. From his post, Scarcelli is already in discussions with other UMSOM eye doctors about developing new microscopes for more diseases like retinal failure.

“We need to meet face to face with clinicians to drive the technology forward,” Scarcelli said. “Exploratory projects and preliminary data are born this way.”

Topics

Research