- March 29, 2022

- By Karen Shih ’09

Covered head to toe in sticky sensors, with wall-mounted cameras trained on me from every corner of the room, I was tempted for a moment to whisper a creepy, “My preciousss.” But nobody would confuse me with Andy Serkis playing Gollum on the set of “The Lord of the Rings.”

My bright-red 1980s-style headband and gym-based surroundings in the School of Public Health Building basement brought me back to reality: I was there for science, not cinema, as a participant in a University of Maryland research study—one of 2,000 involving human subjects currently taking place on campus.

We’ve all seen the posters across campus, tacked up in a bathroom stall or on a bulletin board, recruiting volunteers to do something as simple as take an online survey or join a focus group—or as involved as get your brain scanned in an fMRI machine. Despite being a UMD student, then employee for a decade, I’d never taken the plunge. But as fate would have it, I came across a flier looking for a woman in her third trimester to take part in a walking study, just as I entered my 29th week of pregnancy and had started to develop a noticeable waddle.

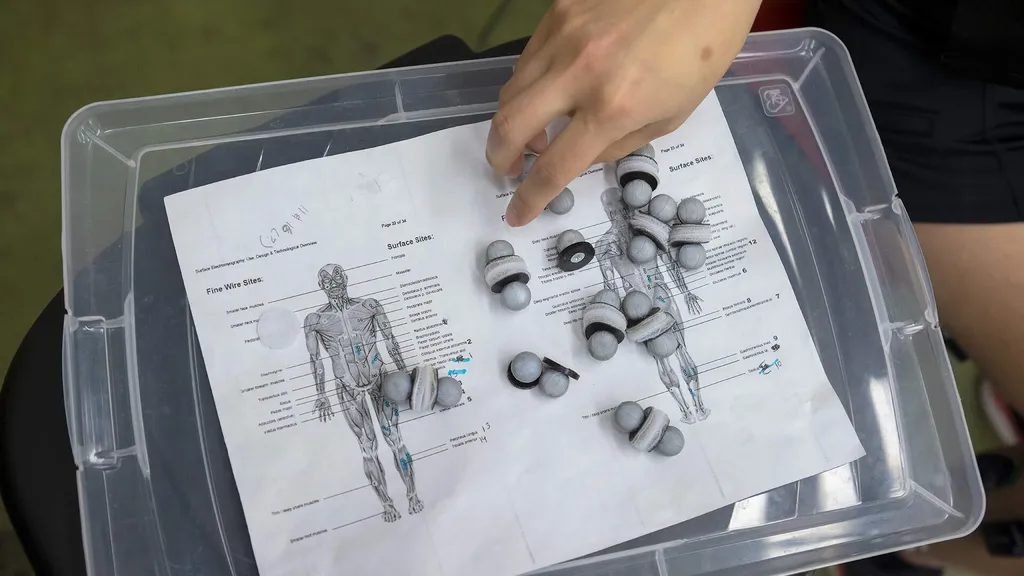

That’s how I ended up hooked up to heart and oxygen monitors and sensors tracking my muscle and joint movements, and taking laps around a track for kinesiology doctoral student Elizabeth Bell over the week of spring break.

“I’m interested in sex-specific factors, like pregnancy, and how they contribute to health disparities,” said Bell, a member of the Neuromechanics Research Core team. Women are at disproportionate risk of knee osteoarthritis later in life, and her study focuses on how gait changes during pregnancy could increase wear and tear on knee cartilage.

Computer modeling and walking simulations have traditionally been male-dominated areas in biomechanics, but thanks to her background in mechanical engineering, Bell is unusually suited to break the mold. She previously worked for Vicon Motion Capture, the company that makes the tracking cameras and creates realistic-looking movements for creatures in movies and video games.

When she became pregnant at the start of her doctoral program, she saw an opportunity to fill a major research gap on the movements of pregnant women.

“Pregnancy is an integral part of the human lifespan, and understanding how pregnancy affects the body may give us insight into how we evolved and where we’re at now,” she said.

Finding pregnant women willing to come to campus during a pandemic was a major challenge, however. Bell first needed to clear the hurdle of the Division of Research’s Institutional Review Board, which has to approve all studies involving human subjects at UMD. Focusing on safety, the IRB considers everything from recruitment fliers to equipment sanitization, and authorizes appropriate incentives, such as cash, extra credit or even pizza for a focus group.

Then, Bell had to find the women in a very specific window of their pregnancy. She advertised on the UMD parents’ listserv and called local doulas (who coach women throughout pregnancy and birth) for recommendations to get the 10 subjects she needed.

“It’s always challenging to recruit, and COVID made it even harder, because people don’t want to have one-on-one contact with you in this era,” she said.

Bell built in additional safety protocols: extensive equipment cleaning because of COVID, the requirement of a doctor’s note clearing each subject for moderate exercise, and modification of traditional ankle, knee and hip strength tests to accommodate the limitations of pregnant women.

It took her three years from her initial IRB approval in March 2019 to collect all of her data—due in large part to pandemic delays—and she sometimes looks back wistfully at the simpler days of her master’s research, when she recruited 28 students into the lab in one month to do push-ups for a study.

Still, no matter the challenges, it’s the human element of research that motivates her as she seeks to “connect research to real outcomes,” she said, from improving prosthetics for amputee patients at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to potentially designing walking adaptations for pregnant women.

As I finished walking and sat down to remove the sensors, Bell swiftly plucked them off with the practice of a mom—“Just treat it like a Band-Aid!” We swapped stories about toddler tantrums, the absurdities of preschool hours and the differences between first and second pregnancies.

“I do really enjoy collecting data and talking to people about their personal experiences,” said Bell. Combining qualitative conversations with quantitative measurements “is necessary to study human movement problems because you need to account for how a person moves and also how they are feeling about the movements.”

IRB by the Numbers

1,921 active studies as of March 15; the most common are survey or focus groups

Top five schools for human subject research:

- College of Behavioral and Social Sciences (especially the Department of Psychology)

- College of Education

- School of Public Health

- College of Arts and Humanities (especially the Department of Communications)

- Robert H. Smith School of Business

Topics

ResearchUnits

School of Public Health