- May 14, 2019

- By Matthew E. Wright

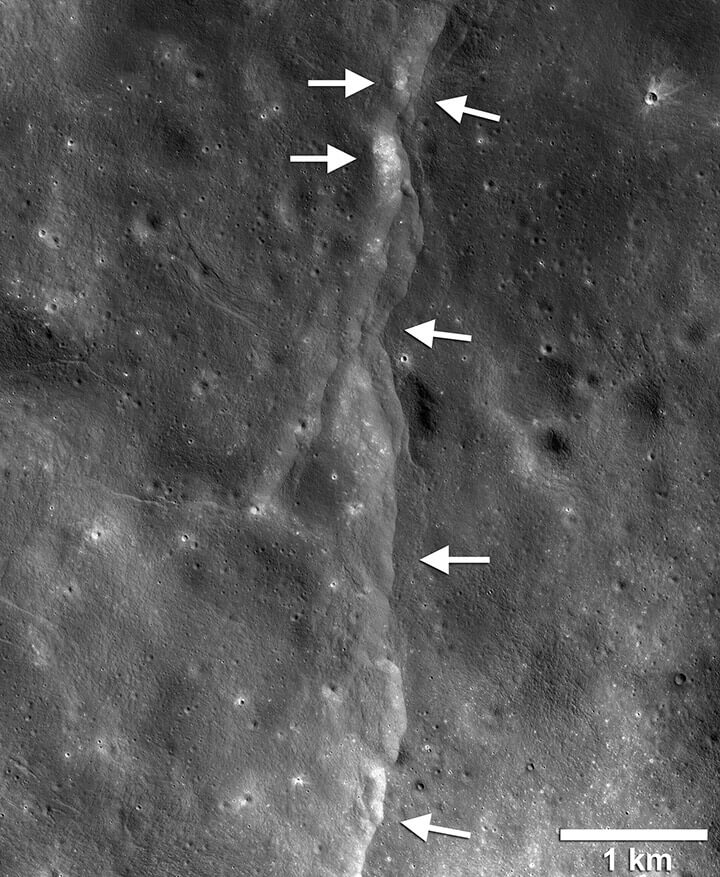

A 2010 analysis of imagery from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) found that the moon shriveled like a raisin as its interior cooled, leaving thousands of cliffs called thrust faults on the moon’s surface sometime within the past 50 million years.

A new analysis suggests that the shrinkage continues, and is actively producing moonquakes along these thrust faults. A team of researchers including Nicholas Schmerr, assistant professor of geology, designed a new algorithm to re-analyze seismic data from instruments placed by NASA’s Apollo missions in the 1960s and ’70s. A paper describing the work, co-authored by Schmerr, was published yesterday in Nature Geoscience.

“We found that a number of the quakes recorded in the Apollo data happened very close to the faults seen in the LRO imagery,” Schmerr said, noting that the LRO imagery also shows physical evidence of geologically recent fault movement, such as landslides and tumbled boulders. “It’s quite likely that the faults are still active today. You don’t often get to see active tectonics anywhere but Earth.”

Their analysis provided more accurate epicenter location data for 28 moonquakes recorded from 1969 to 1977 that on Earth would have ranged in magnitude from about 2 to 5.

The team then superimposed this location data onto the LRO imagery of the thrust faults. Based on the quakes’ proximity to the thrust faults, the researchers found that at least eight of the quakes likely resulted from true tectonic activity—the movement of crustal plates—along the thrust faults, rather than from asteroid impacts or rumblings deep within the moon’s interior.

Schmerr led the effort to produce “shake maps” derived from models that predict where the strongest shaking should occur, given the size of the thrust faults.

The researchers also found that six of the eight quakes happened when the moon was at or near its apogee, the point in its orbit that is farthest from Earth and additional tidal stress from Earth’s gravity makes slippage along the thrust faults more likely.

“We think it’s very likely that these eight quakes were produced by faults slipping as stress built up when the lunar crust was compressed by global contraction and tidal forces, indicating that the Apollo seismometers recorded the shrinking moon and the moon is still tectonically active,” said Thomas Watters, lead author of the research paper and senior scientist in the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Co-authors from NASA Marshall Spaceflight Center, Wheaton College, the University of British Columbia and the Planetary Science Institute also contributed to the research.

The LRO has imaged more than 3,500 fault scarps on the moon since it began operation in 2009. Some of these images show fresh tracks from boulder falls, suggesting that quakes sent the boulders rolling. Such tracks would be erased relatively quickly by a constant rain of micrometeoroid impacts.

With nearly a decade of LRO imagery already available and more on the way in the coming years, the team would like to compare pictures of specific fault regions from different times to look for fresh evidence of recent moonquakes.

“For me, these findings emphasize that we need to go back to the moon,” Schmerr said. “We learned a lot from the Apollo missions, but they really only scratched the surface. With a larger network of modern seismometers, we could make huge strides in our understanding of the moon’s geology.”