- May 01, 2020

- By Samantha Watters

When a trip to the grocery store can induce an elevated heart rate, it’s more important than ever to buy food that we’ll actually eat before it goes bad.

But even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the lack of regulation, standardization and general understanding of date labeling on food products—more than 50 variations in the United States alone, including “best by” and “use by” date—leads to billions of dollars in food waste annually in the nation.

In a new article in Food Control, researchers across the University of Maryland’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources argue that interdisciplinary collaboration is necessary to combat this problem.

“The labeling is the manufacturer's best estimation based on taste or whatever else, and it is not scientifically proven,” said Debasmita Patra, assistant research professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Technology and lead author on the paper. “But our future intention is to scientifically prove what is the best way to label foods. As a consumer and as a mom, a ‘best by’ date might raise food safety concerns, but date labeling and food safety are not connected to each other right now, which is a wide source of confusion. And when billions of dollars are just going to the trash because of this, it’s not a small thing.”

“The labeling is the manufacturer's best estimation based on taste or whatever else, and it is not scientifically proven,” said Debasmita Patra, assistant research professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Technology and lead author on the paper. “But our future intention is to scientifically prove what is the best way to label foods. As a consumer and as a mom, a ‘best by’ date might raise food safety concerns, but date labeling and food safety are not connected to each other right now, which is a wide source of confusion. And when billions of dollars are just going to the trash because of this, it’s not a small thing.”

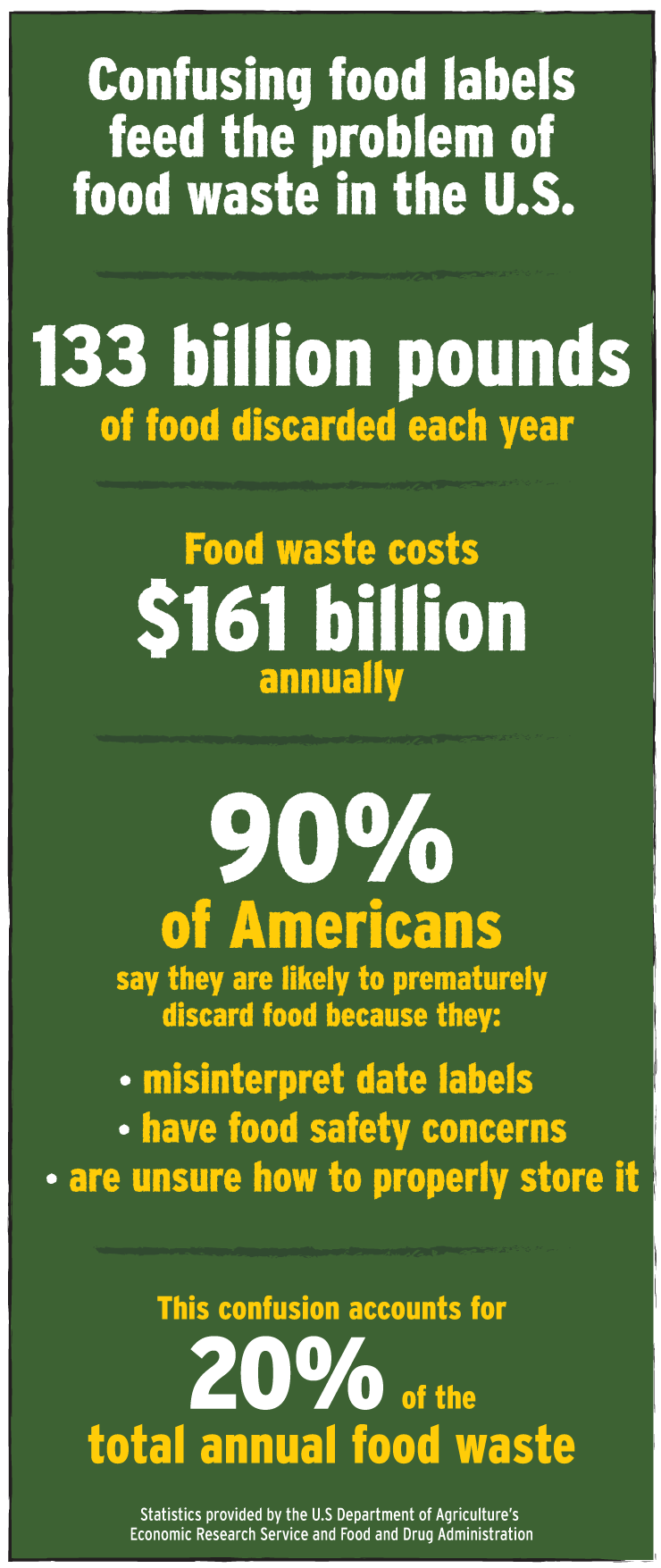

Americans discard or waste about 133 billion pounds of food each year, representing $161 billion and a 31% loss of food at the retail and consumer levels, according to the United States Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service. A whopping 90% of Americans say they are likely to prematurely discard food because they misinterpret date labels, food safety concerns or uncertainty on how to properly store the product, the Food and Drug Administration has found. This confusion accounts for 20% of the total annual food waste in the United States, representing more than 26 billion pounds per year and over $32 billion in food waste.

“Recognition of food waste due to confusion over date labeling is growing, but few studies have summarized the status of the research on this topic,” said Paul Leisnham, associate professor in Environmental Science and Technology and co-author.

He and Patra, along with Abani Pradhan, associate professor in the Department of Nutrition and Food Science, and his postdoctoral fellow Collins Tanui, collectively found that environmental sciences and food science departments don’t seem to collaborate on this topic.

Expertise from environmental science, food science, sociology, extension education and other disciplines can more effectively develop interventions to reduce behaviors that may increase food waste, Leisnham said. While this is an environmental issue, it also involves the knowledge, attitudes, perception and social behaviors of multiple stakeholders, including retailers, food-service providers and consumers.

Pradhan, for example, hopes to use expertise in experimental and mathematical modeling work to scientifically evaluate the quality characteristics, shelf life, and food spoilage risk of food products. “This would help in determining if the food products are of good quality beyond the mentioned dates, rather than discarding them prematurely,” he said.

Patra said the research is relevant to everyone—from producers to wholesale and retail buyers to consumers who open a box or can, unwrap a package of pork chops or peel a fruit.

“People look for something that has a longer ‘best by’ date thinking they are getting something better. And when you throw that food away, you are not only wasting the food, but also all the economics associated with that, like production costs, transportation from the whole farm to fork chain, and everything else that brought you that product just to be thrown away,” she said. “Food safety, regulation and education need to all combine to help solve this problem, which is why interdisciplinary collaboration is so important.”