- December 04, 2023

- By Karen Shih ’09

After nearly 60 years at the University of Maryland, A. James Clark School of Engineering Professor Emeritus Bill Fourney could be relaxing out at his ranch in Colorado. Jetting across the country to visit his four sons and many grandkids. Anywhere but College Park.

But instead, the explosives expert still comes to campus three days a week, working in the C.D. Mote, Jr. Engineering Laboratory to better protect soldiers from brain injuries—and guiding new generations of students as they learn how to conduct research to do good in the world.

“I love to teach,” he said. “That’s why I decided to go into academia, rather than industry.”

He’s always prioritized student interactions, even as he’s taken on leadership roles in the Clark School, serving as chair of both the aerospace and mechanical engineering departments for about a decade each, then as associate dean for undergraduate studies. As chair, for example, he tried to interview every student before graduation to learn how departments could improve.

One of his proudest achievements is creating the Keystone Program with then-Dean Nariman Favardin in 2006. Today, thanks to the extra support and enhanced hands-on experiences it offers to first- and second-year engineering majors, about 75% of them graduate within five years.

Fourney, whose office is nestled in the Keystone suite of the J.M. Patterson Building, explains why he has so many broken objects, the university mementos he’s collected over the years and the story behind a Terps football with his name on it.

Plexiglass explosion

“This is an example of science and art,” said Fourney. “It’s like a lotus petal.”

To understand what happens when a bomb goes off under a vehicle, he created a small-scale explosion in a 4-inch-thick piece of plexiglass in his lab and used a super high-speed camera to capture images of the fracture pattern.

This was part of his work for the U.S. Army, testing prototypes of Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles, used to protect troops from improvised explosive devices and ambushes, and sharing results and recommendations. He recently met the wife of a soldier who survived an attack. “She was grateful,” Fourney said. “Her husband was in an MRAP that got completely, utterly destroyed. And all five of the people inside walked away.”

Busted cans and wheels

In the winter, Fourney burns wood—and his trash. About 25 years ago, he inadvertently put a contact solution saline can into the stove and heard a bang.

“Students tend to understand more if they can see it, so I try to have samples of what we’re talking about whenever I’m lecturing,” he said. The exploded can serves as a vivid visual of how a thin-wall pressure vessel fails. It’s one of many examples he keeps in his office, including a bicycle wheel with a blown-out rim, a deck of cards screwed together to demonstrate horizontal shear, and half of a student-built wooden bridge (less than a foot tall) designed to hold 1,500 pounds.

Watchman’s box and old soda cans

During Fourney’s first few decades at UMD, guards patrolled the campus and checked the security of its buildings. When the university stopped using them and their gray lock boxes, he snagged a couple as mementos. His other campus artifacts include vintage Mountain Dew and Pepsi cans he unearthed during a lab renovation. “Current cans are probably one-fourth of the weight of this,” he said. “These aren’t aluminum—probably steel of some kind—and they’re thick.”

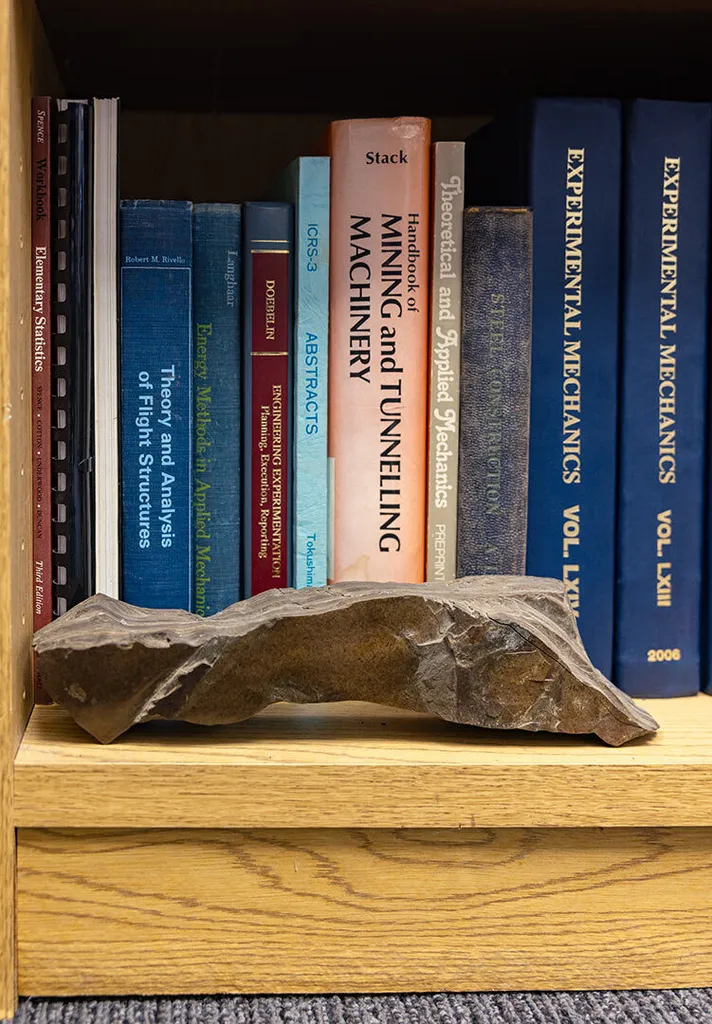

Oil shale

The leathery-looking rock is from a mine in Rifle, Colorado, where Fourney spent a year in 1981 trying to figure out how to extract oil from the shale. The work was in part a response to the previous decade’s energy crisis, when gas shortages drove up prices and forced rationing.

“There’s a huge amount of oil in it, but it’s trapped in the rock,” he said. “We were trying to use explosives to blast it up and retort it—which means heating it underground—to pump oil up.” (His efforts were ultimately unsuccessful.)

Commemorative football

A former high school football player, Fourney has long been a Terps fan (the goal post is from a West Virginia game, where he earned his bachelor and master's degrees). He received the football from a former coach in the 1990s as a token of gratitude for interviewing prospective players interested in engineering, often making a special trip to campus on Saturdays.

“It’s always admirable to me to see a football player out there, but to see one studying engineering, because it’s such a demanding discipline,” is even more impressive, he said.

This is part of an occasional series offering a look inside some of the most interesting faculty and staff offices around campus. Think you have a cool workspace—or know someone’s that you’d like to recommend? Email kshih@umd.edu.