- September 16, 2024

- By Sala Levin ’10

ANDREW LOONEY ’86 sometimes wonders what his life would look like if he’d been born with a different last name. Would he have devoted his personal and professional ambitions to the wide world of whimsy as a Jones or a Smith? Which came first—the name, or the yearning for an off-kilter existence?

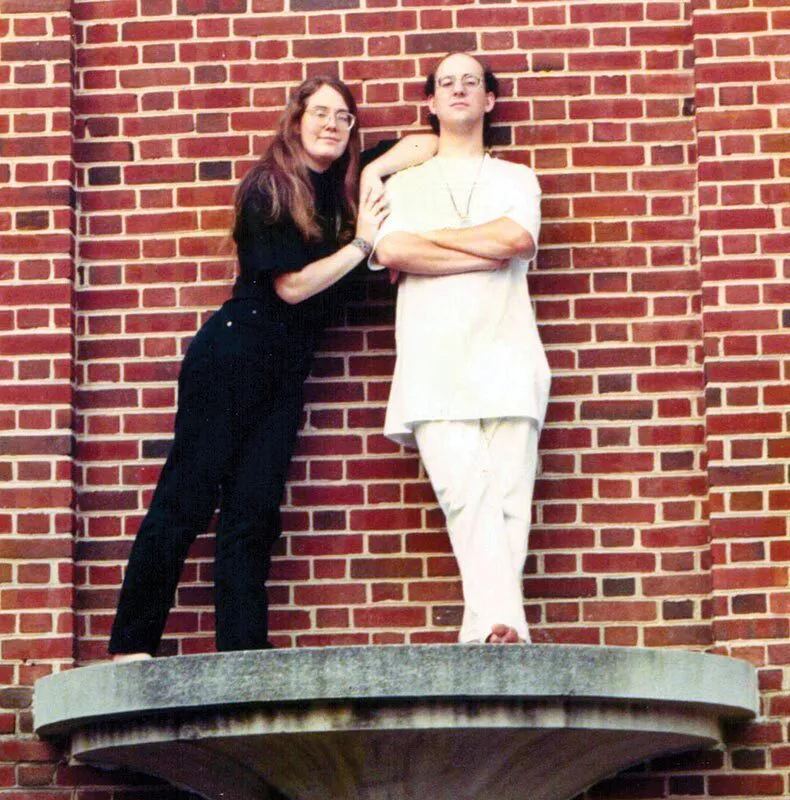

Either way, Looney’s fate was sealed during the summer of 1986 when he met a “hippie chick who doesn’t wear shoes” named Kristin Wunderlich ’88 working at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Her path was preordained as well: In German, “Wunderlich” means eccentric, odd, quirky.

Together, Looney and Wunderlich—long since married and jointly the Looneys—have lived up to the promise of their names. They are the chief creative officer and CEO, respectively, of Looney Labs, the game company behind the card game Fluxx, which has sold more than 4 million copies since its 1997 introduction and spawned spinoffs like Around the World Fluxx, Monster Fluxx and Nature Fluxx.

The game is simple, in theory: Each player starts with three cards and on each turn, draws one and plays one. The game is formless until some cards are played, setting objectives and rules. Each card played reshapes the game. Some introduce a new rule, like “play three” or “draw two.” Others set a new goal that changes the object of the game.

“What got me was the twist, which is there are no rules until you play (a card with) rules, and there’s no way to win until you play a way to win,” says Mike Webb, vice president of sales and e-commerce at game publisher Paizo, who first met the Looneys in the late 1990s while at a different company that distributed Fluxx. “That was just utter genius, and it’s something that made the game have instant appeal to folks.”

Fluxx, Looney Labs’ biggest hit, isn’t Risk, or Magic: The Gathering or Dungeons & Dragons. It doesn’t require players to dedicate hours, or learn an intricate set of rules, or create a backstory for their characters. The game can take as little as 10 minutes, and its strategies are limited.

“One of the most basic breakdowns I like to use (to describe the spectrum of games) is what I call zany or brainy,” says Andy. “Fluxx is very chaotic. So that represents the zany side of gaming.”

Draw some cards, and hop on the Looneys’ zany ride.

Starting Hand: Andy Looney, Kristin Looney, Wunderland

Knock on the door of the lilac-colored house off Rhode Island Avenue in College Park, and Andy Looney might answer the door barefoot, wearing a purple robe, gray hair tied in a long ponytail: one part Gandalf, one part The Dude from “The Big Lebowski,” and one part cleaned-up Jerry Garcia.

Nicknamed Wunderland as a play on Kristin’s maiden name, the house is the de facto headquarters of Looney Labs. (The Looneys rent office space nearby, but since the pandemic rarely use it for more than storage.) To an outsider, the home might look like the warren of a Settlers of Catan-loving packrat—seemingly every inch of it not crucial to functions like walking or cooking is crammed with board games, books, arcade games, collectible figurines. “He does know where everything is,” says Kristin.

Kristin has her own signature look: a tie-dyed bandanna covering her hairline, wavy brown hair tumbling down her back, a tie-dyed shirt doubling down on the vibe.

She’s the warm, focused extrovert to Andy’s sharp, roving-brained introvert. When he thinks of a book that they studied in their early days of game creation (“Gameplan: The Game Inventor’s Handbook”), he wanders off to find the paperback on the packed shelves. Kristin continues the story they’d been telling, happily pausing when Andy comes back to show the exact chapter he was referring to.

“Andy is a person who has wild ideas, and Kristin is a person who can figure out how to make them real,” says Keith Baker, a friend who first met Andy at science fiction conventions in the 1980s. “She’s very whimsical and funny, but she balances that with an amazing sense of how to solve problems and get things done.”

Rewind to Goddard Space Flight Center

Andy was studying computer science at UMD when he accepted a summer job at Goddard, in Greenbelt. The facility was familiar to him; his father was one of the original 157 scientists who transferred from the Naval Research Laboratory to open it in 1959. The family lived off Adelphi Road, near the campus, and games like Sorry! were a central part of life for Andy and his four siblings. “My mom loved getting the kids to play games because they were entertained and she could play with minimal attention,” says Andy.

Kristin had grown up in DeKalb, Ill., 60 miles northwest of Chicago, where she’d been “obsessed” with the game Cosmic Wimpout. (The cloth on which the dice game is played hangs in the dining room of Wunderland.) Kristin loved the game so much that she joined the mailing list of the “tiny little company” that made it, she says—and found out, years later, that Andy had done the same.

After Kristin’s parents got jobs at the National Security Agency, the family moved to Maryland, and Kristin transferred to UMD after two years of studying computer science at the University of Illinois.

Andy was interviewing for a full-time job at Goddard when his future boss talked up a summer employee who was an expert at the Rubik’s Cube—Kristin. Andy realized that he’d seen her on television five years earlier, on an episode of “That’s Incredible!,” an early ’80s reality show that highlighted people’s unusual talents. At the time, she was the fifth-ranked Rubik’s Cubist in the nation, and Andy remembered “the cute blonde girl among the other eight guys” on the show.

Kristin and Andy became friends, and three years later, a couple. This month, they’ll mark their 34th wedding anniversary.

“The moment you meet them, you know there’s something special,” says Webb. “They’re so full of joy, it can’t help but be contagious.”

Create Your First Game

As Andy and Kristin continued their careers at NASA, he also wrote science fiction. One short story, “Icehouse,” included a description of a game he’d made up by that name, based loosely on hearts and played with miniature pyramids.

After a friend helped refine the rules of the game, the duo decided to bring it to life. They started the company Icehouse Games and learned how to make the pyramid pieces in their apartment from a liquid plastic that set in molds. Soon, their landlord threatened to kick them out if they didn’t stop the malodorous process, so they bought Wunderland and moved the setup into a now-demolished shed.

Icehouse was a small success; the Looneys sold it to friends and at gaming conventions, but producing the pyramids was a killer. Kristin begged Andy to make something more practical—a card game, maybe, that could be easily printed and sold to stores. “The next day, he handed me a memo that was the design of Fluxx,” says Kristin. Andy nods. “It was a really good day.”

Draw a Possible Winner, but Discard Valuable ‘Time and Money’ Card

The card game used elements that Andy had been mulling over for years, but essentially popped into his head fully formed, he says. “The ideas will come, and I’ll change it a little bit and then boom, it’s done,” Andy says. “The best ones are always like that. Others, I’ve toiled away at for years trying to figure out how to make it work.”

Kristin created the layout for Fluxx using a database program on an early Macintosh computer. The cards retain more or less the same design today: a stripe along the side denoting what category they belong to (new rule, keeper, goal or action); a brief text explanation; and, on some, a cartoon illustration.

She and Andy hired a publishing company to produce 5,000 copies of Fluxx. When the delivery deadline came and went, and neither of them could reach its staff by phone or in writing, the pair drove to the outfit’s Manhattan offices and parked themselves in the lobby. Soon, they realized that the publishing company had farmed out production to contractors, but spent the money elsewhere.

“They gave us the address of the actual factory, and we drove there and paid them again” to get the game printed, says Kristin.

Swap for the ‘Hit It Big’ Card

Flush with boxes of Fluxx, Kristin and Andy took it on the trade show circuit. At the time, Fluxx (now colorful) was black and white, and the Looneys planned their booth—and their outfits—to match. For four days at their first stop, Origins Game Fair in Columbus, Ohio, they demonstrated the game to enthralled guests. “The sales would just (grow) exponentially from one day to the next,” he says.

That was just their first move. In 1998, three publishers made offers for the rights to Fluxx. (The Looneys sold the rights to Iron Crown Enterprises, but got them back when the company closed several years later.) In 1999, it won the Mensa Select Game Award, given annually to five games that are “original in concept, challenging and well-designed.” (Taboo, Apples to Apples and Scattergories have also won.) That year, the Looneys quit their jobs, he as a programmer and she in IT at an aerospace company.

In a 2007 book on the 100 best hobby games, game designer Rick Loomis wrote that “Fluxx will be busily exercising everyone’s logic synapses as you attempt to deal with the chaotic situations that occur because of the cheerful clash of rules.”

Licensing has been key to Fluxx’s growth. Of the 33 versions of Fluxx on the market, all designed by Andy, some are simply riffs on a theme, like Across America Fluxx or Astronomy Fluxx. (Some of the initial proceeds from Stoner Fluxx, the first spinoff, supported marijuana legalization efforts, a cause close to the Looneys’ hearts.) Others, like Marvel Fluxx or Doctor Who Fluxx, are tied to specific franchises.

The Looneys know their audience. “There are a lot of different types of people that love (the games),” Kristin says. “Nerds,” Andy interjects. “Nerds, yeah,” Kristin agrees.

Draw Lots of Community Cards

The success of Fluxx allowed the Looneys to develop even more outlandish games. Chrononauts is a time-travel card game that asks players to change major historical events to achieve their objective. In Homeworlds, which uses the signature (and no longer homemade) Looney pyramids, players try to destroy their opponents’ home planet before a space fleet strikes their own.

Building a community around the games has been an essential component of the Looney recipe. For years, they’ve hosted game nights, encouraging friends to pluck any box off the shelf. One time, Baker says, a friend brought a buddy from out of town: Weird Al Yankovic. (They played Temple, a card game that features a bit of hazing for players who are bringing up the rear. “Everyone was excited he was there, and yet he just kept losing at this game, and no one really wanted to be mean to him,” says Baker.)

Part of the appeal is the Looneys themselves. The pamphlet that accompanies every game features a picture of the pair. Andy runs a busy blog, where he posts about games, new products from Looney Labs, cannabis and his travels; last year, he planned a road trip based on Across America Fluxx, where he posed in front of Yosemite’s Half Dome and the Las Vegas Strip holding cards from the game with cartoon illustrations of the place. At conventions, he hosts “Andy vs. Everybody” sessions, in which people play games set up in a horseshoe shape while he goes from one to the next to the next—speed dating for tabletop gamers.

“He brings a lot of life to whatever place he’s in,” says Baker. “He’s someone who doesn’t mind doing things other people might think are weird.”

Today, Looney Labs has five full-time employees and a few part-timers, and 62 games on the market. In February, it released Camping Fluxx, and Winnie-the-Pooh Fluxx is coming in September. A new pyramid game, Jinxx, debuted in May.

Still, Andy sometimes worries that Fluxx represents his high point.

“Fluxx kicks the ass of everything else I’ve invented,” he says. “It’s so good that even other things that I make that are really good still pale in comparison to how well that one sells. That’s the paradox of the successful inventor: trying to recapture that magic.”

This story is featured in the Spring 2024 issue of Terp magazine. Find all the stories online at terp.umd.edu.