- July 01, 2016

- By Karen Shih ’09

Waiting: that mundane, invisible, in-between time that we notice only when it becomes a nuisance.

We order through an app to avoid more minutes in a Starbucks line; schedule the first doctor’s appointment of the day to head off delays; grab a flight with a squeaker of a connection to keep from spending an extra second in the airport.

But what if we’ve been thinking about waiting all wrong?

“We like to imagine our futures and reflect on our pasts, but we are so rarely in the present—or if we are, it’s a struggle to get there. Waiting is one of those experiences that puts us in the present,” says American studies Associate Professor Jason Farman, who’s writing a book on the subject. “I’m interested in human perception… how we actually experience time. If our true nature is waiting, as the Zen Buddhists say, then what does it say about us that we try to eliminate it out of our lives?”

Waiting provides a unique perspective into a culture’s views on relationships and knowledge, he says. The expectations and emotions we feel as we wait—decades or months or milliseconds—color the messages we receive.

Farman, a digital technology expert, offers a glimpse, from the dawn of civilization right up to our current, instant-gratification society, of how evolving technologies have changed our relationship with the waiting game.

Tens of thousands of years ago, before written language or papyrus or vellum, the aboriginal people of Australia transmitted messages from tribe to tribe via message sticks. These foot-long, often intricately carved and painted batons conveyed diplomatic missives or friendly greetings, serving as both a mnemonic device for the carrier to interpret and as proof that the message indeed came from its source. Hair or feathers could be attached for identification. For the first time, a shout across a village wouldn’t suffice. These tools connected people who weren’t face-to-face, and as a result, waiting for responses became commonplace, as an essential part of the process that connected societies across distant lands.

The earliest people told time by looking toward the heavens. Then came water clocks and incense sticks, candles and hourglasses. Even as clock towers were erected in the centers of great cities, time remained a fluid thing for the average person, varying from village to village, home to home. But the invention of wearable time—pocket watches and wristwatches became popular during the 16th century and World War I, respectively—and trains, which could travel vast distances in a day and prompted the creation of time zones, led to more exacting standards of timeliness.“Being able to have a watch on us and wearable time, it really changed how we understood time, and had expectations about what being on time meant,” Farman says. “The experience of duration shifted with those objects: commerce, labor, punch clocks and breaks—the regimentation of time really changed.”

The telegraph, the railroad, the affordable postage stamp. These innovations raised expectations among the millions of soldiers fighting the Civil War that they could regularly communicate with the families they left behind.

Before then, a soldier’s family might not know where he was or whether he even lived until he returned home. In the Revolutionary War, only the wealthiest could send mail, which might take months to arrive. But by the Civil War, hearing nothing could inspire anxiety, if not all-out panic.

“Why have you been so remise [sic] in writing to me, have I offended you in any way?” wrote Lottie Putnam to her Confederate sweetheart on March 8, 1864, not knowing he’d been captured. “I beg you, implore you, beseech you, entreat you to tell me why you have not written, and why you have obliterated me from your memory.” (They later reunited and married.)

At the top, President Abraham Lincoln was the first to use the telegraph to instantly contact generals, during the Battle of Gettysburg. It turned out, Farman says, that they preferred waiting. “This was the first time the president was right in your ear, and many of them felt insulted by that presence.”

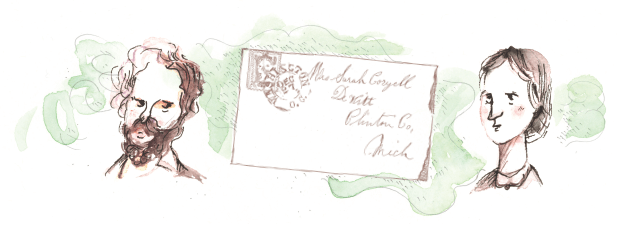

A century ago, a complaint of being “hangry” would get you nowhere. The slang term, meaning hungry to the point of angry, was born of the convenience of 24-hour marts, cheap snacks and prepackaged food. But just a few generations back, even the simplest meal required planning hours, days or even weeks in advance. The animals had to be raised and slaughtered and the plants to be planted and harvested; fires had to be lit and water had to be carried; meat needed to be chopped and vegetables to be washed. And that was before the cooking even began.

The era of fast food—popularized not just by McDonald’s but also TV dinners and the invention of the microwave—changed all that. Today, speed remains the standard throughout the U.S., where a 2011 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development study found Americans spent just 30 minutes a day preparing and cleaning up meals, compared to more than an hour in Turkey and India.

In many parts of the world, hours are set aside for each meal, and the time between courses is part of the experience to be savored. The slow-food movement wants to bring that back to the U.S., urging people to embrace waiting for seasonal ingredients and taking time to cook, chat and pay attention to the dishes and the people around you.

As explorers venture into uncharted territory, Farman says, we imagine their plights in distant lands, whether they’re sailors setting off from ancient Greece; Lewis and Clark across the Pacific Northwest; or soon, the first humans to Mars. Our scope of the world broadens with each week or year they’re gone, as we envision where they could be.

During the Apollo 8 mission on Christmas Eve in 1968, astronauts on the first manned lunar orbit lost radio contact with Houston for 32 minutes when they traveled to the “dark side” of the moon. The millions who watched were captivated. Were there massive craters or mountain ranges we couldn’t see? Creatures of lunar folklore—or aliens? What stories would they tell upon their return?

“We create narratives about their journey, about the new world, about people falling off the end of the world,” Farman says. It’s the waiting period that brings society together, as shared ignorance begets new ideas—and eventually, shared knowledge.

How wedded are we to our cell phones? Subscriptions have surpassed 7 billion—one for every human on Earth. And since 2009, we’ve been more likely to send a text than make a call. “It seemed bizarre to me,” says Farman, who studied UMD students to find out why.

The intrusiveness of ringing a person, instead of a place, pushed them to the more passive medium, he discovered, and the timing of their response often signified the nature of their relationship. For example, they tended to reply more quickly to an acquaintance, like someone calling to set up a meeting for a class project or an interview, rather than friends or family members who were checking in. Farman says, “It’s kind of counterintuitive, but it means, ‘I don’t have to respond right away because you know me.’ Built into that relationship is that you know I care enough that I’ll respond when I get a chance.”

Japanese teenagers think differently, he says. They send blank text messages to their significant others to test their devotion: how quickly they’ll respond with another blank text. The longer the time lag, the more the sender fills it with meaning. “It’s called “flash messaging,” and it’s like a little nudge across distances,” says Farman. “There’s absolutely no content. The content is time. The content is waiting.” TERP

Farman’s book, “Waiting for Word: How Delays Have Shaped History, Love, War, Technology, and Everything We Know,” will be published by Yale University Press in 2017.