- February 04, 2025

- By Laurie Robinson And Jessica Weiss ’05

Indigenous researchers often face significant barriers when seeking records of their communities: outdated catalog systems, inaccessible descriptions and limited access to materials of deep cultural and historical significance. The University of Maryland is taking a groundbreaking step to address these challenges with a new $3.6 million grant from the Mellon Foundation.

The project, led by Diana Marsh, assistant professor in the College of Information, and Shelbi Nahwilet Meissner, assistant professor in the College of Arts and Humanities and director of UMD’s Indigenous Futures Lab, will create systems that make it easier to find and access archival collections related to Indigenous knowledge. Over three years, the team will build tools and standards that respect Indigenous traditions and values, improve how archives are organized and help repair the way information is described.

“A big goal is trying to think differently about how we can describe, represent and search for information that is fundamentally essential to Native and Indigenous communities,” Marsh said. “The antiquated ways this is done are practically impenetrable to a trained archivist, let alone an Indigenous community member trying to track down their materials.”

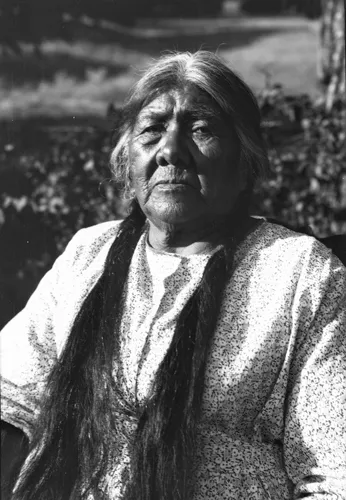

For centuries, colonial collectors—missionaries, anthropologists, government agents—traveled the globe, documenting and seizing Indigenous artifacts and stories under the guise of preservation. Stripped of their cultural context, these records were stored away as trophies and later absorbed into archives that prioritized the collectors’ narratives over the communities they came from.

Meissner, whose ancestors are from the Luiseño and Cupeño tribes of Southern California, has firsthand experience with the consequences of this colonial legacy.

“More than once, I’ve found pictures of my relatives in archives, and their names aren’t listed,” she said. She recalled one instance where an ancestor’s photograph was labeled as “artifact number 47.”

“It’s such a weird and impersonal way of describing somebody who is a great-great-grandmother with 70 great-great-grandchildren,” she said.

A growing movement is transforming archival practices to prioritize Indigenous names, identities and cultural narratives. At the forefront, UMD researchers are collaborating with the Social Networks and Archival Context (SNAC) Cooperative, a free online resource hosted at the University of Virginia Libraries that helps users uncover biographical and historical information about individuals, families and organizations connected to primary sources from cultural heritage institutions worldwide. Additionally, the UMD team is partnering with four Tribal/First Nation organizations and an Indigenous advisory board to shape the initiative.

“The team we’ve assembled so far is amazing and comes from such a diversity of backgrounds and training,” Meissner said. “UMD has the potential to be a key hub for Indigenous research, especially on the East Coast. This is a great opportunity for us to establish best practices for archival sovereignty.”

The project builds on foundational progress, including the development of a guide for best practices in describing Indigenous groups and individuals in archival records. It also draws on the efforts of the Indigenous Description Group, a volunteer-based task force within SNAC that focuses on making archival collections more accessible to Indigenous communities, repairing the harm caused by exploitative collection practices and improving descriptions of Indigenous materials across systems.

Ultimately, the team hopes to elevate Indigenous narratives and bridge the gap between scholars and the communities whose histories they study, Meissner said.

“We want this project to demonstrate how Indigenous and non-Native collaborators can work together,” she said. “By doing so, we can reshape archival practices to reflect the needs and aspirations of Indigenous communities striving to reclaim and revitalize their knowledge.”