- February 21, 2025

- By Sala Levin ’10

From the reliefs on the coins in our wallets to the knickknacks in our homes and the busts that adorn civic buildings, sculpture is pervasive in American life—omnipresent to the point of becoming almost quotidian.

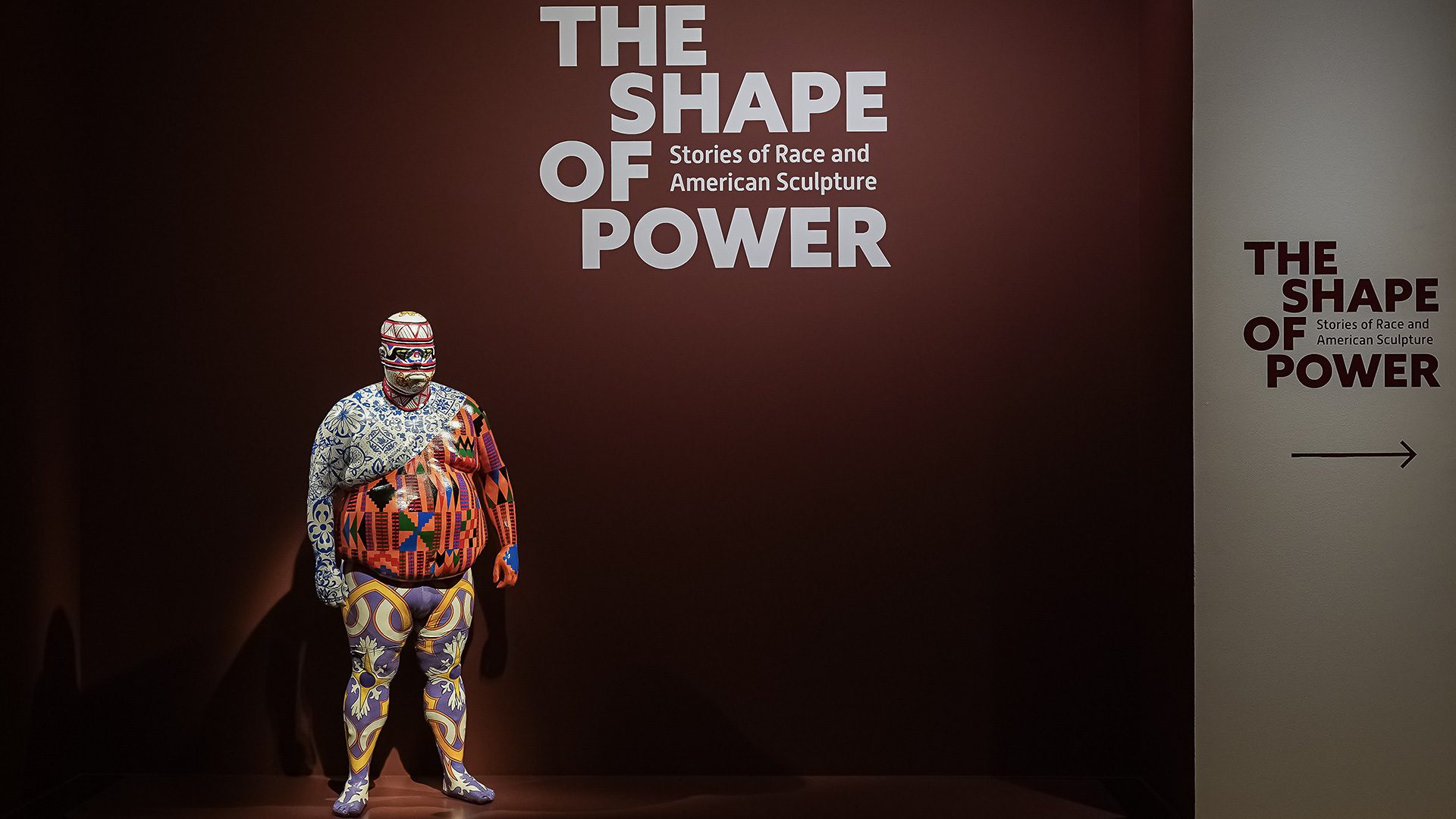

A current exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, co-curated by University of Maryland graduate Grace Yasumura Ph.D. ’19, focuses on the ways in which that omnipresence has shaped and reflected American thinking on race. “The Shape of Power: Stories of Race and American Sculpture,” featuring 82 works created from 1792 to 2023, is “the first exhibition of its kind to examine the intertwined histories of the making of race and the making of sculpture,” she said.

Sculpture, more than other visual art forms, has “an immediate attachment to the body,” said Yasumura. “We recognize ourselves in the work in this really palpable way.” That immediacy, she said, also has the effect of imbuing with authority hierarchies about bodies and physicality—many of which are related to race.

“This is an exhibition that really believes in a public conversation about race in this country and the role that sculpture has played in the establishment and perpetuation of devastating racial hierarchies,” said Tess Korobkin, assistant professor of American art at UMD. This semester, Korobkin is teaching a course that ties into the exhibition; students are visiting the museum several times to meet with curators and conservators to learn how the exhibit came together.

Here, Yasumura walks Maryland Today through some of the pieces on display.

Titus Kaphar, “Monumental Inversions: George Washington,” 2016, wood, glass and steel

This burned-out depiction of the first president on horseback is a callback to the work of landmark 19th-century sculptor Henry Kirke Brown, whose 1856 equestrian statue of Washington stands in New York City’s Union Square. Here, New Haven, Conn.-based artist Titus Kaphar has created a “charred, kind of hollow, shadowy figure” that is “an invitation to think about the histories we’ve inherited and rethink them,” said Yasumura. The blackened elements may remind visitors of Washington ordering the 1779 burning of Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) land in what is now New York State.

Roberto Lugo, “DNA Study Revisited,” 2022, urethane resin life cast, foam, wire and acrylic paint

This colorful piece is based on a body cast that contemporary Philadelphia-based artist Roberto Lugo took of himself. “Sculpture has this long history of being used in very repressive ways,” said Yasumura. “We think of history or science museums, or anthropological studies, that invited sculptors to take body casts of people against their will to study.” Here, Lugo transforms that painful past, creating “an incredibly exuberant and beautiful and intimate self-portrait,” she said. The Kente cloth pattern represents Lugo’s African heritage, while the Taíno markings on his face are a tribute to his Puerto Rican lineage. References to Portuguese and Spanish ceramics nod to Lugo’s work as a potter, while also acknowledging a history of colonialism.

Malvina Hoffman, “Solomon Islander Climbing a Palm Tree,” 1934, bronze

In the 1930s, Malvina Hoffman was commissioned by the Field Museum in Chicago to create bronze sculptures for the exhibition “The Races of Mankind.” Hoffman, who was white, traveled across the world in an attempt to “document and capture in bronze what [museum curators] believed was the biological basis of race,” said Yasumura. The exhibition, which was on display for more than 30 years, was enormously influential, with the sculptures making their way into school textbooks and maps. “One of the really interesting challenges of this exhibition, and what a lot of museums are facing, is how to responsibly address such works,” she said.

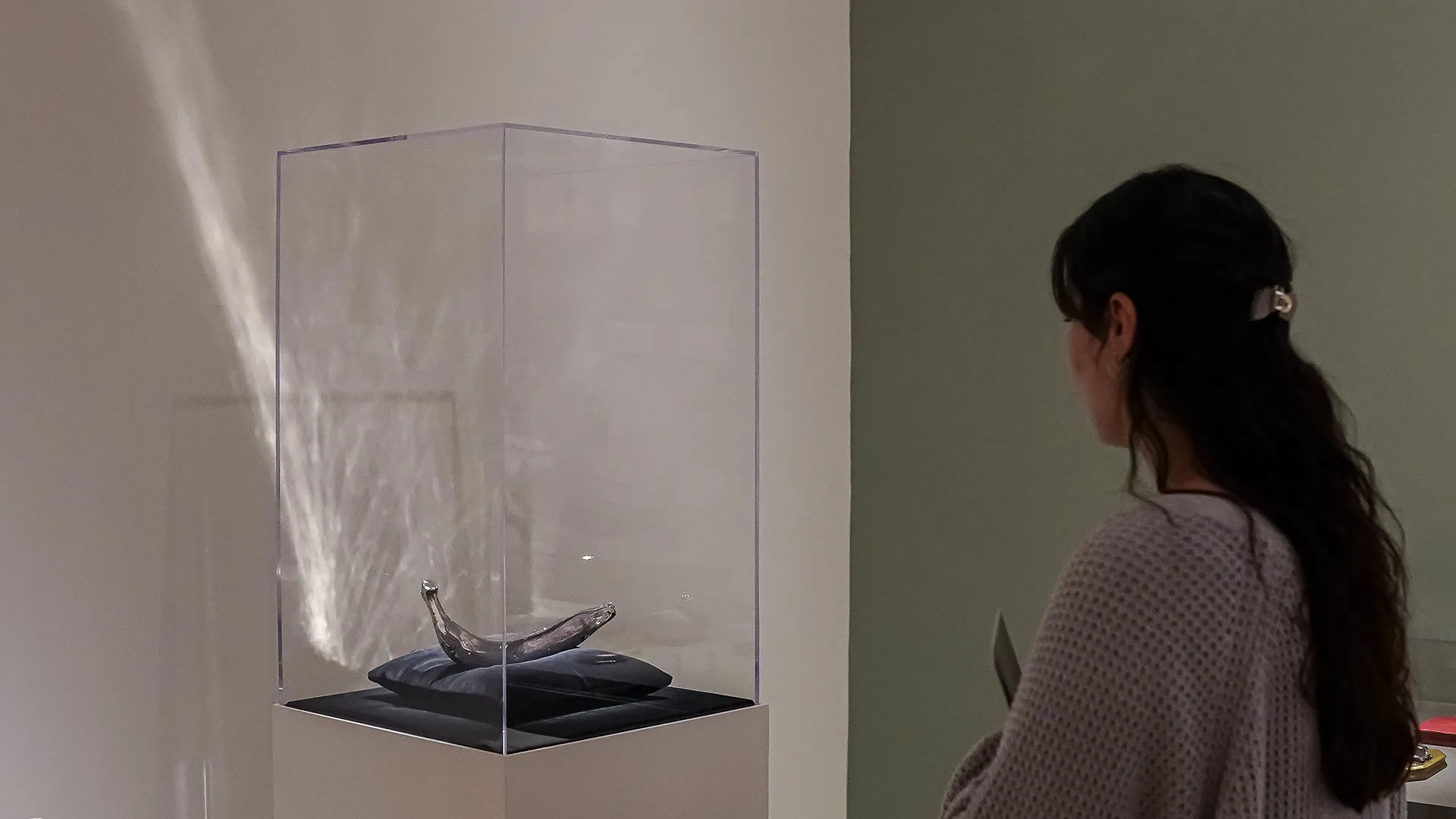

Miguel Luciano, “Pure Plantainum,” 2006, green plantain plated in platinum and velvet cushion

Puerto Rican artist Miguel Luciano uses the plantain—central to Caribbean cuisine and culture—as an irreverent, platinum-covered symbol of pride in this piece. Puerto Ricans in New York City were often derisively referred to as “plátanos,” the word for plantain, during the huge wave of immigration in the middle of the 20th century. Still, “the plantain has also been this symbol of pride in Latin communities,” said Yasumura. Here, Luciano has subverted stereotypes of Puerto Rican immigrants by gilding the beloved plantain in platinum, turning it into a precious object both monetarily and emotionally.

Bob Haozous, “Apache Pull Toy,” 1988, painted steel (above, far left)

In this piece, artist Bob Haozous, a citizen of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe, plays with the American trope of cowboys and Indians. Historically, Indigenous people have been “turned into mascots and toys to be shot at as part of the fantasy of the old West,” said Yasumura. Here, Haozous turns the cowboy into a plaything riddled with bullet holes. “He’s playfully questioning how damaging these histories are, and he’s thinking about how generations of American children were taught to think about Indigenous people.”

“The Shape of Power” is on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through Sept. 14. The museum is open daily from 11:30 a.m. to 7 p.m.

This is one of a series of Maryland Today features during Black History Month celebrating Terp faculty, staff, students and alums.