- September 08, 2025

- By Karen Shih ’09

While many 17-year-olds last spring were preoccupied with planning for prom, studying for AP exams or booking houses for beach week, Hannah Cairo was shocking the not very teen-coded world of theoretical math.

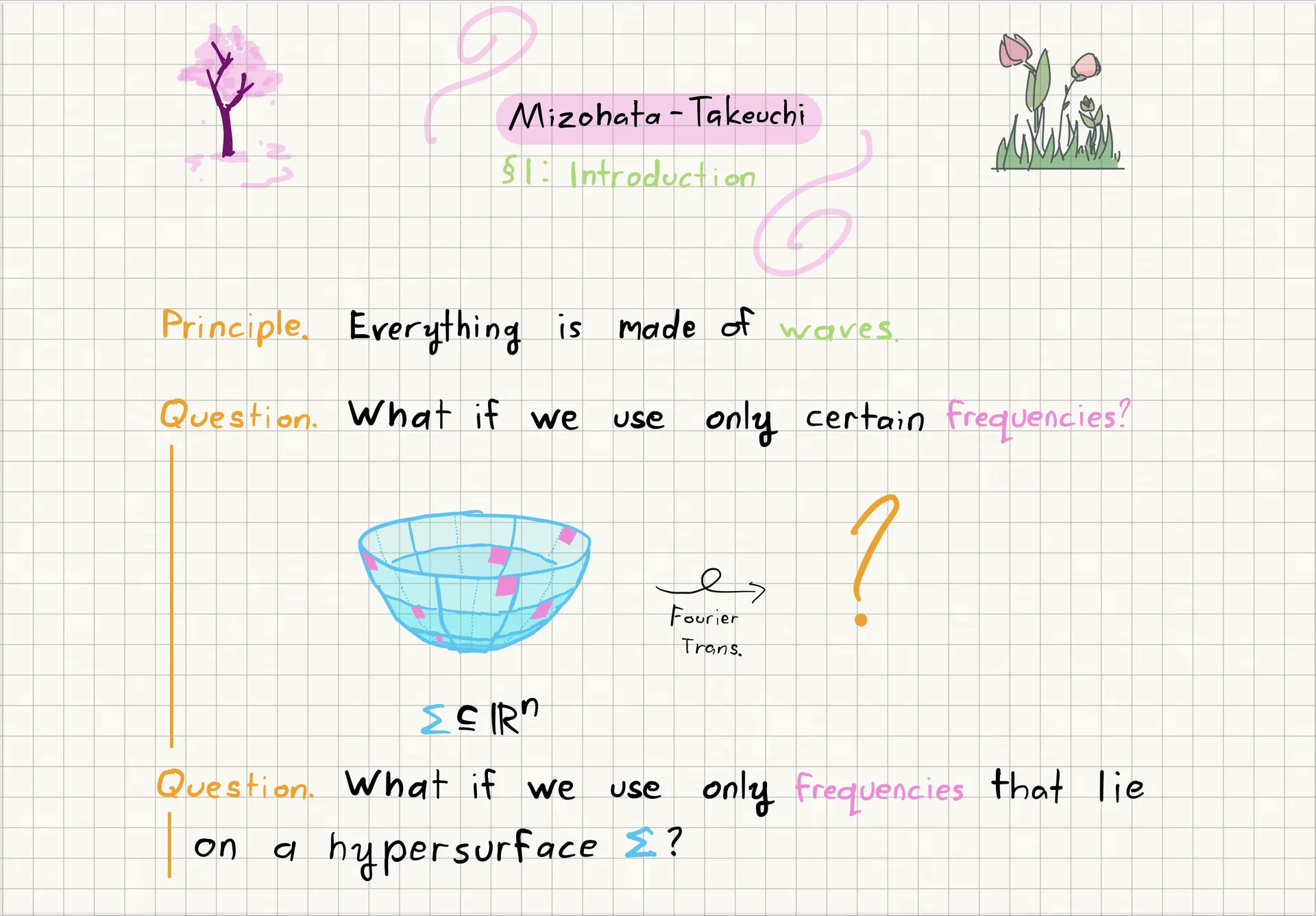

In February, she disproved the Mizohata-Takeuchi conjecture, a math assumption that had stumped experts around the world for 40 years (and is impossible to summarize in lay terms). And she did it as a side project to her classes.

“Once I start working on a problem, it’s kind of addictive,” she said. “I can’t stop thinking about it. For every question I answer, I just have more questions.”

Now the remarkable teen will pursue those answers as she starts her doctoral studies at the University of Maryland this fall.

“She stands out head and shoulders above her peers,” said math Professor Wojciech Czaja, comparing her to prodigies like alums Charles Fefferman ’66, who won the Fields Medal, math’s highest honor, and George Dantzig ’36, who famously solved two open problems in statistical theory after mistaking them for homework. Cairo didn’t just tackle “a niche question that a small group of people were interested in. This is a well-known problem, spanning various areas of math.”

Growing up in the Bahamas, Cairo was homeschooled. Her affinity for math became apparent early as she raced through the Khan Academy’s online curriculum, learning calculus by 11. She pored over math textbooks on topics like analytic number theory under the guidance of tutors, finding beauty in the numbers and ideas. It was sometimes a lonely experience, but she found like-minded people when she joined her first math circle, extracurricular gatherings of mathematicians and students.

“They bring math puzzles and everybody collaborates, and it’s a really nice way to make friends,” she said.

That led her to apply at age 14 to the Berkeley Math Circle online summer program, where she found both challenge and camaraderie. A few years later, her family moved to California, and she joined Berkeley’s concurrent enrollment program to take graduate-level math courses.

One of those was on Fourier restriction theory, a branch of harmonic analysis, an area that has wide-ranging applications from telecommunications to music analysis and even image processing.

A few months in, Professor Ruixiang Zhang assigned a simplified version of the Mizohata-Takeuchi conjecture in homework. Cairo quickly completed the assignment—but couldn’t stop thinking about the problem. She spent months on proofs, consulting Zhang along the way, before coming up with her construction to disprove the conjecture.

She posted it to arXiv.org in February, and within a few months, she gave a talk at a prestigious math conference in Spain. Since then, she has gotten media coverage in Scientific American, Quanta Magazine and international new outlets.

A slide from Cairo's presentation on disproving the Mizohata-Takeuchi conjecture. (Courtesy of Hannah Cairo)

It could be overwhelming, but Cairo, despite being soft-spoken, is eager to share her work.

In person, “it’s funny when people try to guess my age,” said Cairo, now 18. With her quiet poise, she’s often mistaken for a postdoc or a grad student when she’s among fellow mathematicians—but when she volunteered at a summer program, was mistaken for a camper. “I don’t hide my age, but I don’t want to brag about it.”

Maryland was eager to recruit Cairo, led by math graduate program director Leonid Koralov. Now, he and Czaja are eager to help her maximize her potential at UMD. She’ll continue to research Fourier restriction theory, but they also hope she can examine “other questions of importance to modern science,” said Czaja.

Cairo also hopes to explore additional opportunities on and off campus. As a trans woman, she hopes to increase visibility for LGBTQ+ students, and she’s also joined an animal rights student group. Once she’s passed her qualifying exams and settled in, she hopes to start a math circle for K-12 students in the local community, using games like Nim and Set to pique their interest.

“Mathematics to me is like an art, but in school they don't really teach it that way,” she said. “If you’re just memorizing steps, you’re not learning how to build things with ideas, paint pictures with ideas. I want to try to help people do that.”