- April 08, 2024

- By Robert Herschbach

A caravan of 30 University of Maryland undergraduates, two graduate students and two faculty members, as well as friends and family are part of the nationwide wave of skywatchers traveling to an ideal spot to experience Monday’s total eclipse. But they’ve also descended on the outskirts of Muncie, Indiana with a scientific mission, one involving a pair of high-flying balloons.

As part of NASA’s Nationwide Eclipse Ballooning Project (NEBP), the Terps are among students from 75 colleges and schools who have fanned out to locations in 13 states along the path of totality.

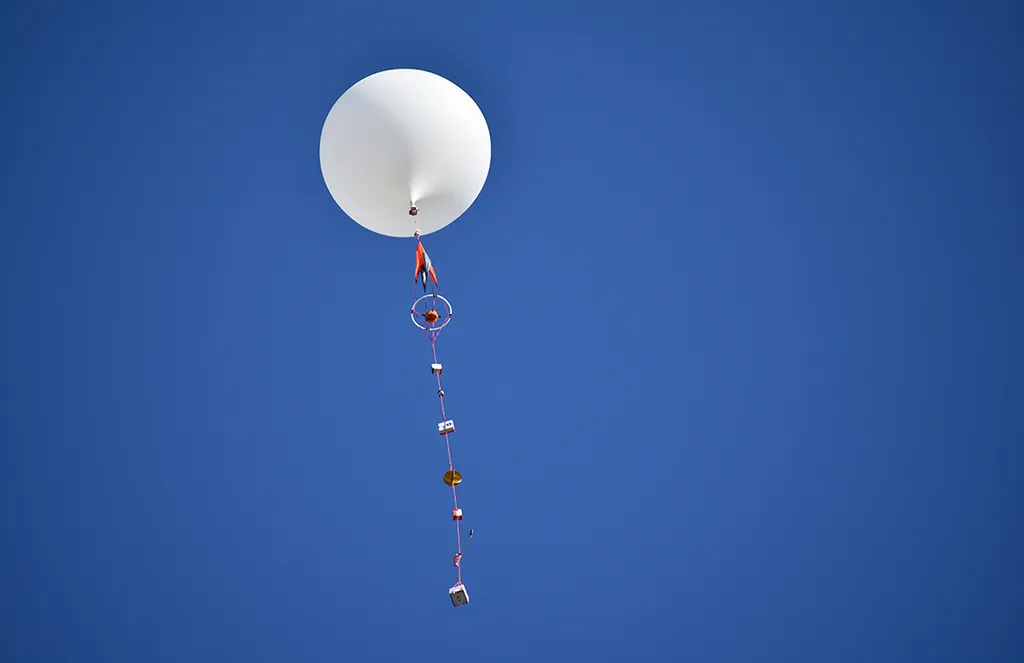

Students in the Balloon Payload Program, known as UMD Nearspace, will launch their two high-altitude weather balloons within 15 minutes of each other at the beginning of the eclipse. They’ll soar to between 70,000 and 80,000 feet high during totality.

One balloon will be stocked with atmospheric sensors designed to glean data that will help improve weather forecasting and even our ability to model climate change. The other balloon, dubbed Terp Balloon, will carry UMD experiments, including one designed to track how environmental exposure affects 3D-printed samples.

The students will monitor the temporary cooling of the air caused by the moon blocking the sun’s radiation.

"The eclipse itself is kind of stirring up the atmosphere as it traverses across the country," program Director and Department of Aerospace Engineering Senior Lecturer Mary Bowden told National Public Radio, which profiled the team earlier this month. "What we're looking for is the signature, or the effect, of the movement of the shadow."

Balloons, she said, are uniquely well-suited to carry out such measurements, since they can drift through the atmosphere for an extended period. Getting them up there, and keeping them on track, during a short time window is a challenge, however—one that requires careful appraisal of the launch site, wind conditions and the balloon’s trajectory. Among other variables, the team must correctly calculate the amount of helium needed to achieve sufficient lift as the balloon carries its payloads skyward. With the period of totality lasting under four minutes, there’s no margin for error.

Although the team hopes its efforts will contribute to research, Bowden stressed that UMD Nearspace’s main purpose is educational.

“Many of our aerospace students are intensely interested in the space side of the field, so we’re giving them an opportunity to go through an experience that's very similar to building flight hardware and launching it into space,” she said. “It's motivational, it's educational, and it's really just fun!”

Watch the Eclipse on Campus

The new moon will start to cross the face of the sun at 2:04 p.m. and obscure 87% of the sun at maximum eclipse, which occurs at 3:20 p.m. The eclipse ends at 4:33 p.m.

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences, Department of Astronomy; and Space Sciences Outreach Cooperative will host a watch party outside Glenn L. Martin Hall from 1:30-4:30 p.m. Free solar eclipse glasses that meet ISO standards will be available until supplies run out. In the case of inclement weather, the event will move inside the Physical Sciences Complex lobby to watch a live webcast from within the path of totality.

Women in Engineering will host a Maryland Dairy ice cream social and viewing party with free eclipse glasses from 2-4 p.m. on the Martin Hall patio. Rain location is the Martin Hall lobby.