- April 30, 2025

- By Karen Shih ’09

THAT CHILL IN THE EGG AISLE isn’t just refrigeration. Grocery runs these days can feel a bit Soviet, with signs announcing carton rationing and apologizing for low stock. Even Waffle House—known for holding the line on prices—added a 50-cent surcharge to egg dishes.

The once-affordable source of protein has become scarce for one reason: the latest strain of avian influenza, H5N1, a highly contagious and fatal virus. Over 168 million birds have either died of the virus or been culled over the last three years. Most of those were egg-laying hens, which drove the average price of eggs up more than 60% by the end of 2024, with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) predicting a 50% spike in 2025.

The disease is spreading rapidly through wild birds, decimating waterfowl and even killing our national bird, the bald eagle. Alarmingly, it’s jumped to mammals as well. Cats are particularly susceptible, including pets, wildlife and zoo animals like lions and tigers; dairy cattle are a new host, putting at risk another grocery staple, milk.

And as of April, 70 people have been infected after contact with diseased animals and one has died, fueling worries about human-to-human spread and a possible next pandemic.

But long before most of us had heard of bird flu, University of Maryland researchers were already working to better understand it and curb its spread. Extension specialists are developing and disseminating the best biosecurity guidance to keep farms secure. Epidemiologists are tracking the virus’ path into and across the country. Lab researchers are using novel methods to understand the origins of avian influenza itself.

“We have to prepare for the worst and hope for the best,” says veterinary medicine Assistant Professor Mostafa Ghanem. “We have to do our best to contain it outside of humans as much as we can. No one can predict how (bird flu) will evolve.”

Researchers have tracked “low-pathogenic” strains that produced mild symptoms like weight loss or lower egg production. In the 1990s, however, the far more dangerous H5N1 emerged in China and spread among wild birds, before conquering other nations in Asia and moving west. (In 2015, a related H5N2 strain reached the U.S.; farmers were able to eradicate it the next year by culling more than 50 million birds at a cost of $1.6 billion.)

Then the H5N1 strain evolved and reemerged in 2021 to affect more wild birds, including raptors like owls and scavengers such as black vultures. It has since spilled over into domestic poultry as infected birds stop at a farm or surrounding areas, leaving virus particles in saliva, nasal secretions or feces. Outbreaks are most common during fall and winter migrations.

Now the virus persists year-round, says Associate Professor Jennifer Mullinax of the Department of Environmental Science and Technology. “We’re not seeing the drop-off we expect. The normal pattern is changing.”

OUT WHERE MARYLAND’S EASTERN SHORE shrinks to a narrow strip, sandwiched between the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, sits Farhan Nasir’s poultry farm. He rises every day at 5 a.m. to check his 18 chicken houses in Pocomoke City, where he’s raised about 1.25 million broilers—meat chickens—each year for Perdue Farms for more than a decade.

When bird flu reemerged with a vengeance this winter, striking eight farms on the Delmarva peninsula in January, he and his fellow farmers were terrified. Nearly half of Maryland’s agriculture production comes from chickens, and on the Eastern Shore, it rises to about 75%.

“There’s a general sense of doom around,” says Nasir. “It’s very stressful psychologically and financially for the community.”

When bird flu strikes, chickens show symptoms like coughing plus swelling and discoloration in the legs and head. The state Department of Agriculture then works to quickly contain and “depopulate” a farm’s entire flock. Next, the affected farm must wait at least two weeks—but sometimes months—and test negative for environmental contamination before it’s eligible to bring chickens back, creating major financial losses for farmers.

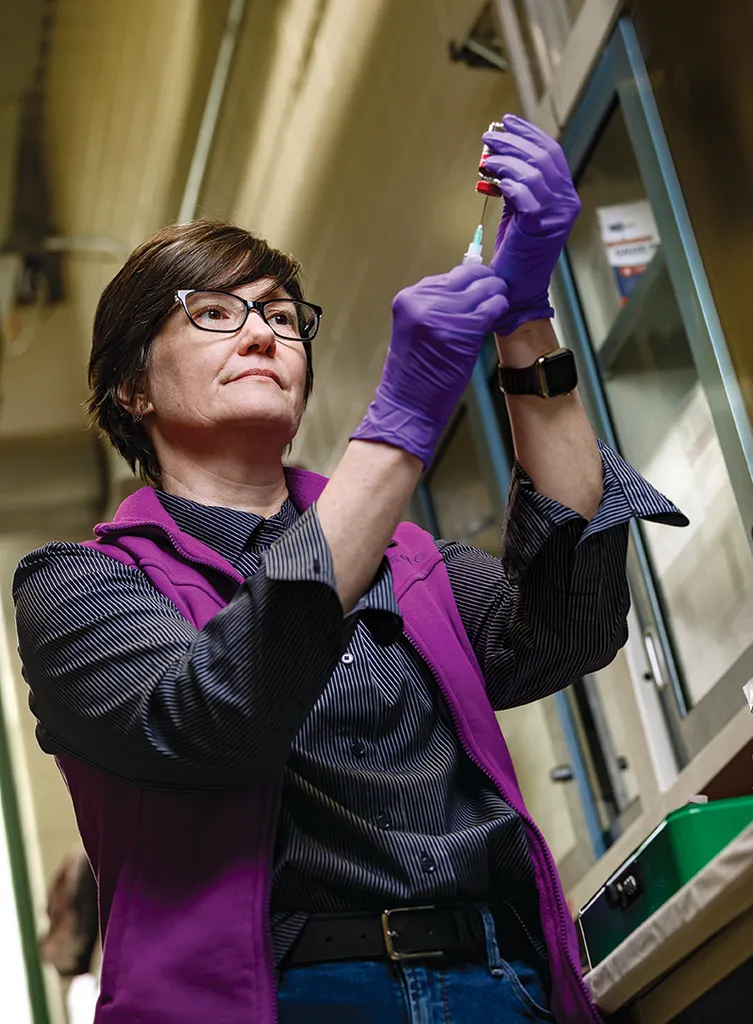

To help farmers stave off catastrophe, UMD Extension has created an education and outreach campaign on the importance of “biosecurity” procedures. These include having dedicated clothes and shoes for each chicken house, as well as bleach footbaths (right), to avoid tracking in contaminants that could contain avian flu; sanitizing trucks and cars carrying deliveries the farm; frequent handwashing and cleaning of high-touch items like glasses and cell phones; and scaring wild birds away with dogs, coyote silhouettes and even auto dealer-style inflatable tube men.

The economic consequences have farmers taking serious measures to secure their flocks, says UMD Extension poultry specialist and Principal Agent Jonathan Moyle, a former chicken farmer who has worked on biosecurity measures for more than a decade. “When I first came here, I was told what we’re seeing today, like changing shoes and using foot baths, would never happen. Now our farmers are doing all of it.”

Nasir followed every recommendation, then asked for instructional videos in Spanish for his employees, which the Extension quickly provided. And when buzzards started plucking chicken carcasses from the compost, Moyle helped him test various methods of discouragement until finally, reflectors and plastic buzzards kept the scavengers away, preventing further spread of the virus.

Soon, Nasir and his colleagues will have a new and improved tool to pinpoint farms that are most at risk, thanks to a College of Agriculture and Natural Resources team.

Mullinax and researchers from her Applied Spatial Wildlife Ecology Lab have been tracking H5N1 since it emerged in the U.S. in 2022. They documented its routes across the country, examining where it’s spilling over from waterfowl into domestic poultry, between farms and occasionally, back into the wild.

“The virus itself is constantly changing,” says Mullinax. “I wish we could tell you, ‘It’s this bird in that place’ (carrying it), but that’s not reality. It’s a wickedly complicated system.”

Now she and postdoctoral researcher Matthew Gonnerman, in collaboration with Diann Prosser Ph.D. '12 of the U.S. Geological Survey, have developed a model incorporating waterfowl habitats, environmental factors like waterways and topography, the prevalence of disease in different avian species, as well as farm locations and biosecurity measures. Once they publish their data, they’ll release their models for broader use, tailored for state and federal agencies as well as commercial and backyard farmers, who can use the results to prepare for oncoming waves of the virus.

With more data, “we hope to not just understand correlation, but be able to predict what’s coming next, and who’s most vulnerable throughout the year,” Mullinax says.

WHAT’S COMING, UNFORTUNATELY, could bring economic and health consequences far broader in scope than just wild birds and chicken farms.

In March 2024, H5N1 was detected in dairy cattle in the U.S.—the first infection in cows anywhere. Cattle respond differently; rather than exhibit respiratory symptoms, they had reductions in milk production and mild fever, so farmers initially didn’t think to check for avian flu or take steps to stop it. The disease has since spread to cattle in 16 states.

The virus was likely introduced by wild birds and then transmitted from cow to cow, says Ghanem, who studies the molecular epidemiology of infectious diseases and manages a USDA-funded project on bird flu biosecurity.

Then it made another jump. As of April, 41 people have been infected with bird flu via dairy cows, reported the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), though human symptoms have mostly been mild. The challenge is that dairy farms require far more human workers than poultry farms, which are largely automated, Ghanem says. Milking is still done manually, and many people interact with the milk as it’s processed.

“We don’t want the virus to adapt to humans,” he says, so increased biosecurity efforts, ranging from personal protective equipment to better testing, is key.

A cattle vaccine in development by the chair of UMD’s Department of Veterinary Medicine, Professor Xiaoping Zhu, could help stop that jump. In April, Zhu and Wenbin Tuo from USDA’s Agricultural Research Service received funding from the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture to adapt nasal spray technology they originally developed for COVID-19 and human influenza. By delivering a protein to the nasal passages that blocks viruses from infecting cells in the respiratory tract and preventing infections from starting, this greatly reduces the likelihood of humans and other animals contracting the virus from cows.

And another mammal is at risk, with even closer ties to humans.

Felines have long been susceptible to avian influenza, dating back at least 20 years to cases in Asia among both large cats on wildlife preserves and barn cats. The newest strain is particularly deadly, with about a 90% mortality rate, presenting a clear risk for the more than 74 million pet cats in the United States.

Cats “are not being monitored for H5N1. It’s a big black box,” says School of Public Health Assistant Professor Kristen Coleman, an airborne infectious disease researcher who previously studied animal-human spillover events in Asia. She’s found a drastic increase in the number of cats reported with the disease, starting in 2023.

Along with outdoor feral colonies contracting it from wild birds, the virus started showing up in indoor-only cats. The culprit is raw pet food, an unregulated industry that can source its meat from anywhere, including wild game, Coleman says.

“In the best-case scenario, pets remain a dead end and don’t become a vector” to humans or other species, she says. “But even in that case, cats are the victims, and a lot of people’s hearts will be broken if they lose their pets.”

Coleman is now working to collect blood samples with animal rescues and veterinarians in California, where several cat deaths have been connected to cattle outbreaks as well as to contaminated pet food, and in Maryland, where cat cases are starting to emerge. She’ll identify how widespread the virus is and eventually alert workers in those industries about what precautions to take.

The CDC reported two possible cases of spread between felines and humans from May 2024, and there was at least one confirmed case in 2016. “Cats open up a whole new vulnerability,” she says.

YOU’RE PROBABLY NOT THINKING about ducks when you’re on day three of the flu, shivering under your sheets and surrounded by a pile of used tissues. But it’s deep in their guts (or the bowels of fellow waterfowl) that all flu viruses originate. Human seasonal flu—which likely jumped from birds to humans many years ago—is even part of the same family, influenza A, as bird flu.

To better understand how new influenza viruses develop, avian and animal science Assistant Professors Andrew Broadbent and Younggeon Jin, and cell biology and molecular genetics Associate Professor Margaret Scull, supported by a UMD Grand Challenges Grant, are using “organoids”—lab-created stand-ins for intestines and tracheas cultured from tissues of chickens, turkeys and ducks—a more humane option than infecting live birds.

“We’re trying to understand: How are new strains of avian influenza made? Is it more likely to happen in duck hosts or chicken hosts? Which cells is it happening in?” says Broadbent.

As they infect the organoids with various strains of avian influenza, they’ll compare how the viruses interact with different types of cells, including how they break through the body’s natural protective barriers, and evolve within different bird species (and they hope to create organoids from other duck breeds and other wild bird species like gulls in the future). Eventually they’ll be able to determine which virus mutations make certain fowl more susceptible, which could help field researchers determine the strains most likely to jump from wild birds into different types of poultry.

Their work to date has focused on low-pathogenic strains, though they plan to move into high-pathogenic strains in the future. Their findings will have long-term implications, because avian influenza is here to stay. There’s no way to eradicate it from waterfowl, so even if this deadly strain is stopped, others will pop up again, whether next year or next decade.

But there’s good news: Scientists already know a lot more about influenza than about coronavirus. The USDA also has conditionally approved a vaccine for poultry, though it is not currently used because of poultry export agreements (some threatened wild species, like condors, have been immunized, however). Now, Broadbent is partnering with School of Medicine Assistant Professor Lynda Coughlan through a University of Maryland Strategic Partnership: MPowering the State grant to test a new H5N1 vaccine in chickens this spring.

“This situation is very different from COVID, where we had to start from scratch,” he says, noting that vaccines exist for humans as well, though they haven’t been deployed because bird flu is still rare in people. In addition, “H5N1 is sensitive to antiviral (treatments), which we didn’t have against coronavirus.”

As of April, there are still no cases of human-to-human transmission, and the CDC considers the public health risk low. So while you might have to work in some egg substitutes and keep Mittens from slipping outside, it’s OK to keep living your life, UMD researchers say.

“We don’t need to go into panic mode,” says Mullinax. “The people at risk are the ones working in the industries every day. But we should be aware of what’s happening, because we will likely have to deal with this long-term.”

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Food

• Buy only pasteurized milk. Avoid the raw product.

• Cook poultry and eggs to an internal temperature of 165 degrees F.

Pets

• Keep cats indoors so they don’t come in contact with wild birds.

• Don’t feed your cats raw pet food.

• Call a vet immediately if your pet has respiratory or rabies-like symptoms, and request that they be screened for avian influenza.

Wildlife

• Avoid dead animals and droppings.

• If you see a dead or sick bird, call the Maryland Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Services hotline.