- May 02, 2023

- By Maggie Haslam

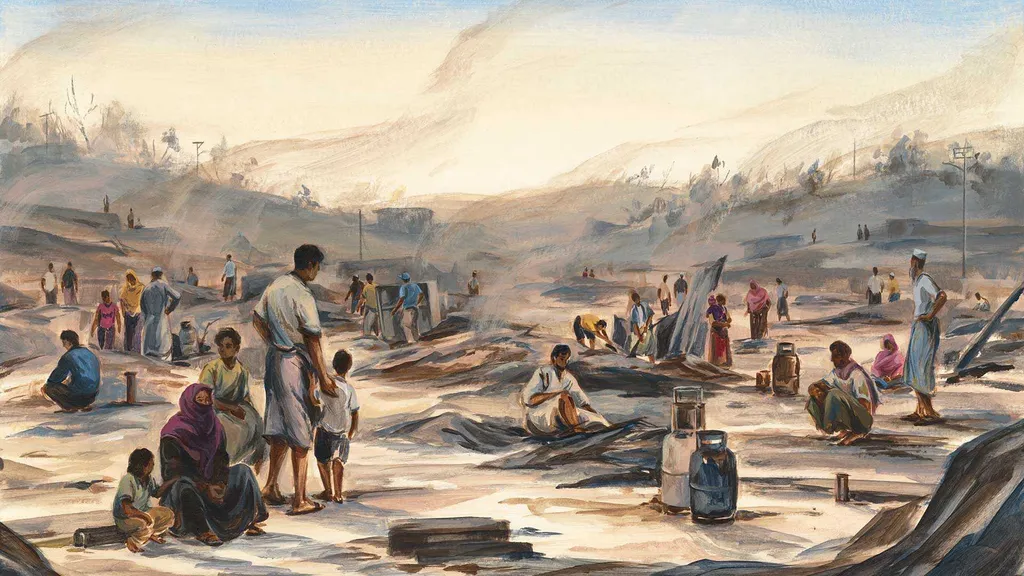

In the afternoon hours of March 22, 2021, as women attended to chores and children played in dusty streets, a fire erupted at Kutupalong Balukhali in the Cox’s Bazar region of Bangladesh, the largest refugee camp in the world.

Aided by wind, parched conditions and an abundant fuel source—the bamboo and plastic tarp composing thousands of densely packed shelters across the camp’s hilly terrain—the fire ripped swiftly through makeshift homes, warehouses, medical facilities and mosques. Within two hours, it had engulfed more than 4 million square feet of the asylum for nearly 1 million Rohingya refugees who fled ethnic persecution in neighboring Myanmar.

As the fire marched south, hundreds of gas cylinders used for cooking burst like small bombs. Residents poured into the camp’s narrow streets, first to fight the fire—then to flee, frantically searching for family members or doubling back for their meager belongings, only to be caught in the chaotic flood of evacuees escaping the rapidly advancing flames, heat and thick smoke.

The fire burned for seven hours, scorched over 160 acres, killed 15 people and displaced another 45,000. According to emergency responders on the scene, the magnitude of the fire, lack of water and narrow roads hampered their efforts; the fire was only controlled once there was nothing left to burn.

The circumstances that displace refugees—from violence and persecution to war and increasingly, the impacts of climate change—are nothing short of traumatic. According to the United Nations’ Refugee Agency (UNHCR), 103 million people have been forcibly displaced worldwide, more than the entire population of Germany. Of that, 32.5 million become refugees. Those who flee to humanitarian camps bear the scars of their arduous journeys and circumstance, as well as the trauma of leaving behind their homes, possessions and communities.

While reports of fires in humanitarian settlements briefly graze global news feeds, no one seems to be running a tally. These types of fires are poorly tracked and even more poorly understood, setting the stage for a repeating history with no end in sight, said Danielle Antonellis, a fire protection engineer who’s founder and executive director of Kindling, a nonprofit that supports and inspires fire safety in vulnerable communities around the world.

“When you think about these people who have been displaced and have nothing, that are vulnerable in so many ways,” Antonellis said, “and then you strip them down one more level—that’s the definition of a humanitarian crisis.”

Not long after the fire in Bangladesh, James Milke ’76, M.S. ’81, Ph.D. ’91, chair of UMD’s Department of Fire Protection Engineering, began a collaboration with Kindling and fire researchers from Stellenbosch University in Cape Town, South Africa to better understand the causes and order of magnitude of fires in informal settlements—the often-ramshackle housing that comprises much of the world’s slums and shelters millions of displaced people. Like Antonellis, Milke sees the fire threat there, as well as within formal refugee camps, as an urgent global problem. Under his leadership, the department is collectively one of the country’s foremost authorities in fire behavior, material flammability, fire detection and wildfires.

“There are informal and humanitarian settlements on every continent on the planet,” said Milke, who plans to conduct the next phase of the research this summer. “Fire isn’t the only problem they face, but when it occurs, it is devastating to the people who live there.”

Milke recruited a legion of young people—from Maryland high school students to Terps at the undergraduate and graduate levels—to gather and organize data and confer with faculty at Stellenbosch, experts at Kindling and frontline responders. Students conducted initial investigations of fire phenomena in informal settlements in South Africa and generated preliminary modeling and simulations of evacuations using Pathfinder software and Google Earth imagery. A challenge with informal settlements, however, is the hands-off approach of local governments: There is no overseeing body with which to collaborate on possible interventions or solutions. Further conversations with colleagues at Stellenbosch suggested a shift to refugee camps.

“In refugee camps, organizations like the United Nations have some influence as to what these communities look like,” Milke said. “We realized we might have greater impact there.”

Milke’s team began by researching and cataloging refugee camps globally, scrubbing through humanitarian reports and the wider internet. Their growing roster included the locations, size, demographics, and topography of camps, cooking and heating methods, fire incidents, and various materials used to construct dwellings and service areas.

It quickly became clear that no two camps are alike. The urgency and economics of quickly establishing refugee camps by UNHCR and NGOs, coupled with the socioeconomic and political underpinnings of the host countries, drive everything from how densely populated the camps are to the materials used to construct shelters. Climate also plays a critical role, particularly in areas like Bangladesh that contend with wet and dry seasons. Locations are often small, undesirable parcels of land that can be hours from emergency services. Families are typically provided gas cylinders for cooking; at any given time in Kutupalong Balukhali, there could be hundreds of thousands of fires lit throughout the camp.

Though the Rohingya have occupied parts of Bangladesh since the 1970s, the government’s insistence that this is a temporary arrangement means they do not allow for permanent construction materials—refugees use whatever is available in ample supply, often highly flammable materials. Satellite imagery shows tightly packed clusters of dwellings crosshatched with narrow dirt roads.

“It’s ad hoc,” said Dan Graham, a safety and rescue technical specialist and program manager working in Bangladesh for the international humanitarian organization Migrant Offshore Aide Station (MOAS). “There’s no grid system or numbering; people build their shelter where they dump their stuff and can get their hands-on materials. The density is something I still don’t know how to articulate, and the blunt reality is that apart from the metal cooking pots and water pumps, everything in that environment is flammable.”

In 2022, Milke and then UMD graduate student Genevieve Tan ’21, M.S. ’22 joined researchers from Stellenbosch and MOAS’ Richard Walls and Paul Chamberlain to look more closely at Kutupalong Balukhali and piece together what took place—from the path of fire to response and evacuation—during those seven hours in March 2021. Investigations after fires in refugee camps are often stymied by a lack of resources, but also a lack of evidence, says Antonellis.

“When these big fires occur, we never really find out from a scientific perspective why something happened the way it did,” Tan said. “There is a need for academia to develop methods for data collection and reporting, and use that information to characterize and understand the problem.”

Milke, Tan and their fellow researchers relied heavily on conversations with first responders and refugees on WhatsApp, on-the-ground accounts, information from international organizations and media coverage. Theirs was the first detailed documentation of a large-scale refugee camp incident in academic literature.

While engineering plays an important role in understanding the issue, Antonellis points out, it is just one piece of a complex puzzle that cannot be solved without also considering the economics, social dimensions and politics at play. The humanitarian system, a mechanism set into motion by disaster or conflict, must make quick decisions about the construction and management of camps as refugees pour into them.

“Fire risk is emerging as the camp is created,” Antonellis said. “It’s easy to say, ‘Why don’t you space the tents further apart or ban candles?’ From a technical perspective it feels like a straightforward problem to solve, but it’s not a technical problem: It’s a sociotechnical problem.”

Fire behavior in humanitarian dwellings is vastly different than in a building fire. Fanned by ample fuel sources and airflow, the intensity and speed with which fires in refugee camps spread are more akin to a wildland fire, explains Maryland Engineering Professor Arnaud Trouvé. Human behavior is also a factor; most people, said Trouvé, misinterpret the speed of fire, which can travel faster than a human can run.

The human element of fire is what ultimately drew Tan to fire protection engineering. At Maryland she studied disaster resilience through an internship with the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which offered her an eye-opening view of the struggles people face in informal settlements.

As Tan began her graduate degree, the timing of Milke’s work with Kindling couldn’t have been better. Under Milke and Trouvé’s guidance and supported by a John L. Bryan Graduate Research Assistantship, Tan developed a thesis project to quantify the fire risk and burn behavior of humanitarian shelters using a YouTube video of a shelter fire conducted by UNHCR’s Site Management Engineering Project. Using MATLAB-based image processing, Tan compared the video with an identical dwelling created using Fire Dynamics Simulator, a modeling software that until now has only been used to model room or building fires. She was able to reconcile characteristics including flame height, temperature, intensity, heat release and spread—critical steps for understanding the unique characteristics of shelter fires.

In the future, Tan’s model could be configured to different dimensions, material properties and contents (such as furniture) as more and better data become available. Simulations based on her model could help understand the risk of spread and may inform the spacing of dwellings. Today working in fire safety consulting and system design for Baltimore-based Jensen Hughes, Tan hopes her research provides a foundation for another student to pick up where she left off.

“I had such a limited scope of data to work with, and the nature of the problem makes things very hard to nail down right now,” she said. “But it’s so important for people to continue working in this space.”

As research on fire risk in humanitarian settlements continues— at Maryland, and at just a handful of other universities around the world studying the problem—so do the fires. On March 5, 2023, yet another massive fire ripped through Rohingya refugee camps in southeastern Bangladesh, displacing an additional 12,000.

According to Deb Niemeier, the Clark Distinguished Chair of Energy and Sustainability at Maryland Engineering, it’s only been within the last decade that engineers have begun to work on the logistics of global humanitarian challenges such as the refugee crisis from the inside as it became clearer they could make a significant impact. Research can help bridge the significant firsthand knowledge from organizations like the UN High Commissioner for Refugees with the practice and models to understand how solutions could work on the ground.

“Engineers are terrific at figuring out logistical concerns,” Niemeier said, “so the role for engineers is huge. We can work on very specific issues like fire risk and raise a vigilant, observant practice so that it’s safer.”

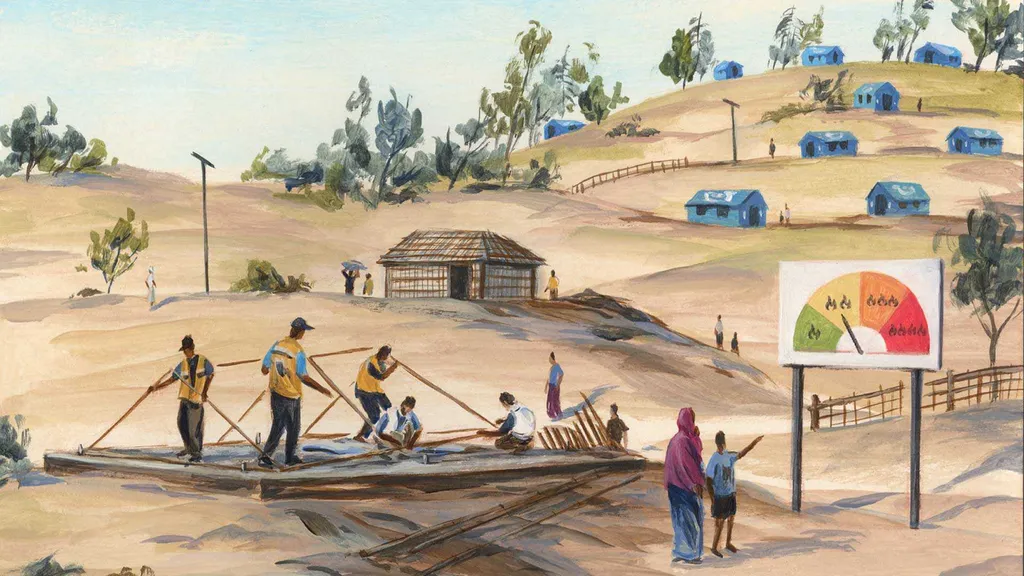

Ongoing collaboration and idea exchange with the academic community, said Graham, is essential for creating not just global awareness, but also a global response. He said that research, like the kind undertaken by Milke and students at Maryland, will keep the issue at the fore—as well as provide the foundation, best practices and knowledge to establish fire management standards for refugee camps. Those standards could include a hazard warning system, similar to those used in high-risk wildfire areas, based on environmental conditions and density of the camps to alert refugees to take care with open flames and cooking.

“‘Red flag days’ have proven very effective for raising awareness in other parts of the world,” Milke said. “Could we accomplish the same here?”

This summer, Milke plans to return to where he started by completing the first complete picture of global refugee camps and fire phenomena, having students document fire events in Asia and updating the existing database. It’s a critical tool for the global community in appreciating how big this problem really is, he said. The department also hopes to continue the research that Tan started by looking at the speed and progression of fire spread from one dwelling to two or three.

“This is where academia can make the biggest difference,” said Antonellis. “We need research like what’s happening at Maryland to push under the noses of practitioners and stakeholders to provide them with the information they need to make better decisions. “It’s transformative for our work.”

Topics

Research