- October 15, 2019

- By Jessica Weiss ’05

Richard Bell was digging through archives in the Library Company of Philadelphia in 2011 when he paused on a 180-year-old newspaper article about a kidnapper who reportedly took her own life while serving time in a Delaware jail.

Bell, an associate professor of history at the University of Maryland, was researching a book about suicide. But he was less captivated by Patty Cannon’s death than by how she made a living: kidnapping free black children and trafficking them into slavery.

Cannon and her band of criminals were the starting point in what became “Stolen: Five Free Boys Kidnapped into Slavery and Their Astonishing Odyssey Home,” Bell’s harrowing, heartbreaking book published today. Lured from their Philadelphia homes in 1825 by the false promise of work, the boys—Sam, Enos, Alex, Joe and Cornelius—spent months at the hands of a black-market network of traffickers that marched them over a thousand miles, from the Eastern Shore of Maryland into the South.

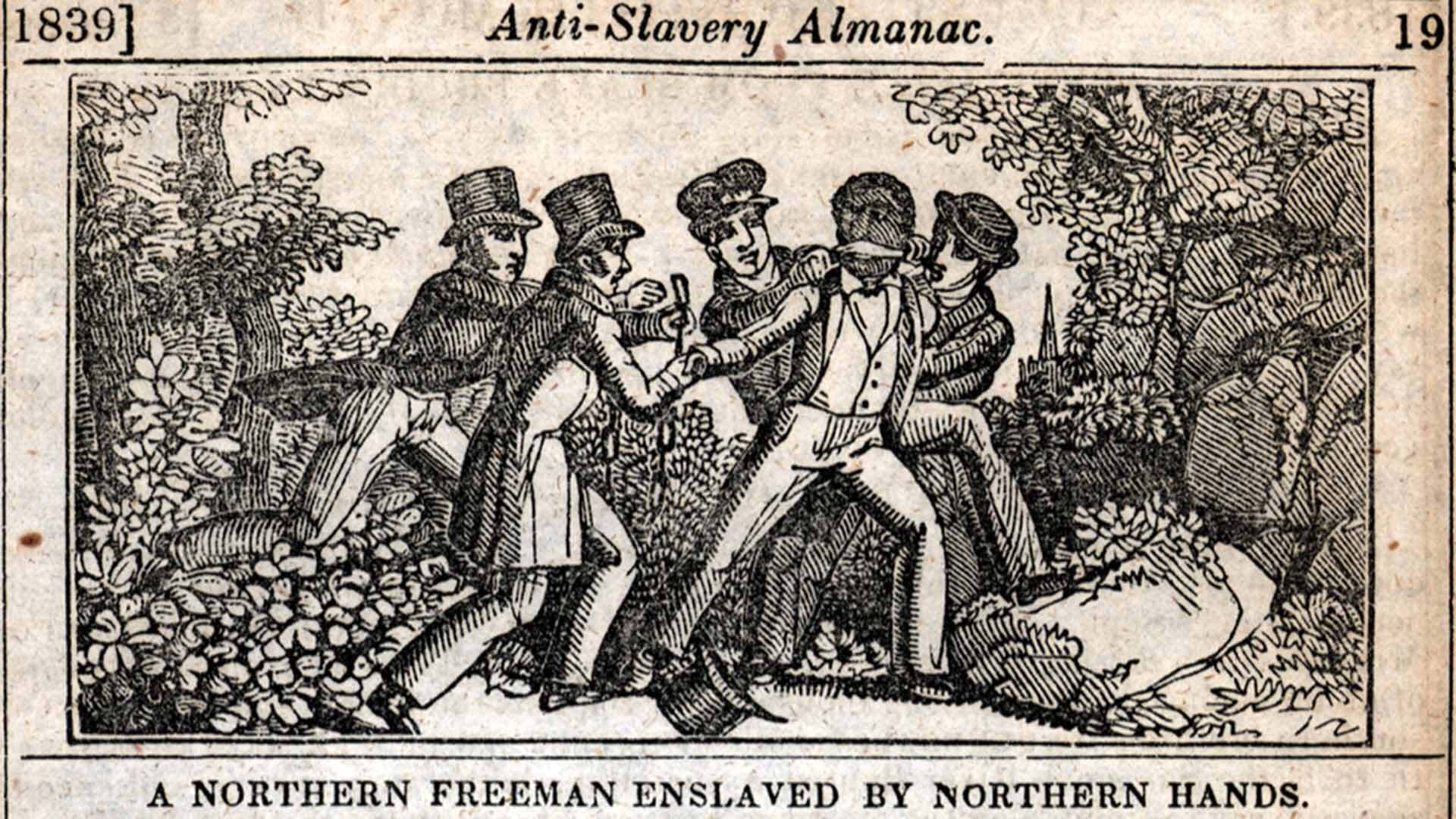

Bell knew little about this horrific slice of American history until he came across Cannon’s record. Since then, the film adaptation of Solomon Northup’s 1853 slave memoir, “Twelve Years a Slave,” brought mainstream attention to what Bell calls the “Reverse Underground Railroad.” Bell spoke with Maryland Today about the arduous process of reconstructing the saga at the heart of “Stolen” and what it adds to the commonly accepted narrative of slavery.

Bell knew little about this horrific slice of American history until he came across Cannon’s record. Since then, the film adaptation of Solomon Northup’s 1853 slave memoir, “Twelve Years a Slave,” brought mainstream attention to what Bell calls the “Reverse Underground Railroad.” Bell spoke with Maryland Today about the arduous process of reconstructing the saga at the heart of “Stolen” and what it adds to the commonly accepted narrative of slavery.

These five boys don’t have memoirs like Solomon Northup. In fact, only one of them could read or write. So how did you piece together this epic tale?

Over eight years working on this project, I went to 35 archives in 14 states and the District of Columbia, from very fancy archives in D.C. and Philly to courthouse attics and dusty archives in the Deep South.

The most significant source I used is coverage from a Philadelphia magazine called The African Observer, which was broadly sympathetic to African American freedom struggles and therefore quite rare. The largest part of the source base is a series of about 30 or so letters either to or from the mayor of Philadelphia when he gets involved in trying to recover these five boys from Alabama and Mississippi to bring them back to Philadelphia. But I also used 100 other small sources—from tax records to medical bills—to build out the story and be able to tell it with a degree of texture and richness and immediacy. I found things that had never been discovered before, like a missing persons ad placed by the father of one of the boys, and letters from one of the kidnappers while he was doing jail time, begging for a pardon or clemency.

The book combines scholarship with storytelling and reads like a novel. Why did you decide to tell this story with literary flair, with narrative?

The book combines scholarship with storytelling and reads like a novel. Why did you decide to tell this story with literary flair, with narrative?

I wrote this book for as many readers as possible. Many of the academic history books that we write are argument-driven, rather than narrative-driven, and idea-driven rather than character-driven. That sometimes limits their appeal beyond academia or beyond academic courses. So, the hope is to have written a book of interest to general readers because the story of these five boys being kidnapped and trafficked into slavery is representative of a tsunami of similar stories which are harder to recover. And if we can understand one story, we can better understand the contours of the trafficking of thousands, if not tens of thousands, of free black people into slavery between the Revolution and the Civil War. This is an undeniably important scholarly subject, but if scholars are the only people to learn about this, then this is a missed opportunity to help the public grapple with the complex legacy of race and slavery in the U.S.

The state of Maryland played an important role in this saga. Can you explain the importance of its geography?

This story opens in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and takes the reader to Alabama and Mississippi, but along the way the state of Maryland looms pretty large, and a lot of the action in the early part of the story does take place in Maryland. The gang of kidnappers have their headquarters in the middle of the Delmarva Peninsula, right on that Maryland-Delaware state line. They live in buildings there, but they also use them as warehouses or safe houses for the trafficked children they are trying to remove from Philadelphia and get into the legal labor market for slaves in the Deep South. So, the Eastern Shore of Maryland is a staging post of this vast network—what I call “the Reverse Underground Railroad” in the book—that allows thousands of free black adults and children to be kidnapped and trafficked into slavery in the Deep South.

And it’s a very safe place for kidnappers and human traffickers to warehouse the victims of their kidnapping. What’s so striking is that no one in the surrounding community on the Eastern Shore in the 1820s can find the courage and confidence to blow the whistle on the neighbors down the street whom they know to be kidnappers and human traffickers.

What was most revelatory to you in writing this book?

I was startled and dismayed by the scale of how often the kidnapping of free black adults and children went on, and the degree to which children in particular were targeted. I was surprised by the degree to which the people doing the kidnapping tended to be from the margins of rural society, and that some of them were actually African American or mixed race. The role of women in these kidnapping collectives also struck me as surprising. And it struck me as doubly surprising, given all I thought I knew about how slavery worked, that on occasion there were white slaveholding Southerners who would intervene to do something to stop particular kidnapping cases.

What do you hope people take away from reading your book?

That the line between being free and being unfree has never been bright and clear and that freedom in America has often been fragile. And that even being free from slavery is not the same as living free of racial discrimination, for instance. As the families of the boys in Philadelphia would tell you if they were here, they can be legally free but still have no job and no place to live.

I would hope readers come away with the understanding that the security of marginalized Americans has been continually threatened by predators of various sorts looking to exploit them for personal gain and that having freedom papers is not always enough to protect you.

And on the flip side, I hope readers of “Stolen” notice too that its story is also a story full of people who sometimes act against their own interests for the greater good … that ordinary people have made history in America again and again and again.

Topics

Arts & Culture