- September 08, 2020

- By Maryland Today Staff

A handwritten letter from Georgia O’Keeffe. A photo with Lady Bird Johnson. Correspondence with towering artist Romare Bearden.

In “The David C. Driskell Papers,” a new virtual exhibit from UMD’s David C. Driskell Center for the Study of Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora, these materials and more commemorate the life of the famed artist, curator, scholar, educator and mentor, who died April 1 of complications from COVID-19 at age 88.

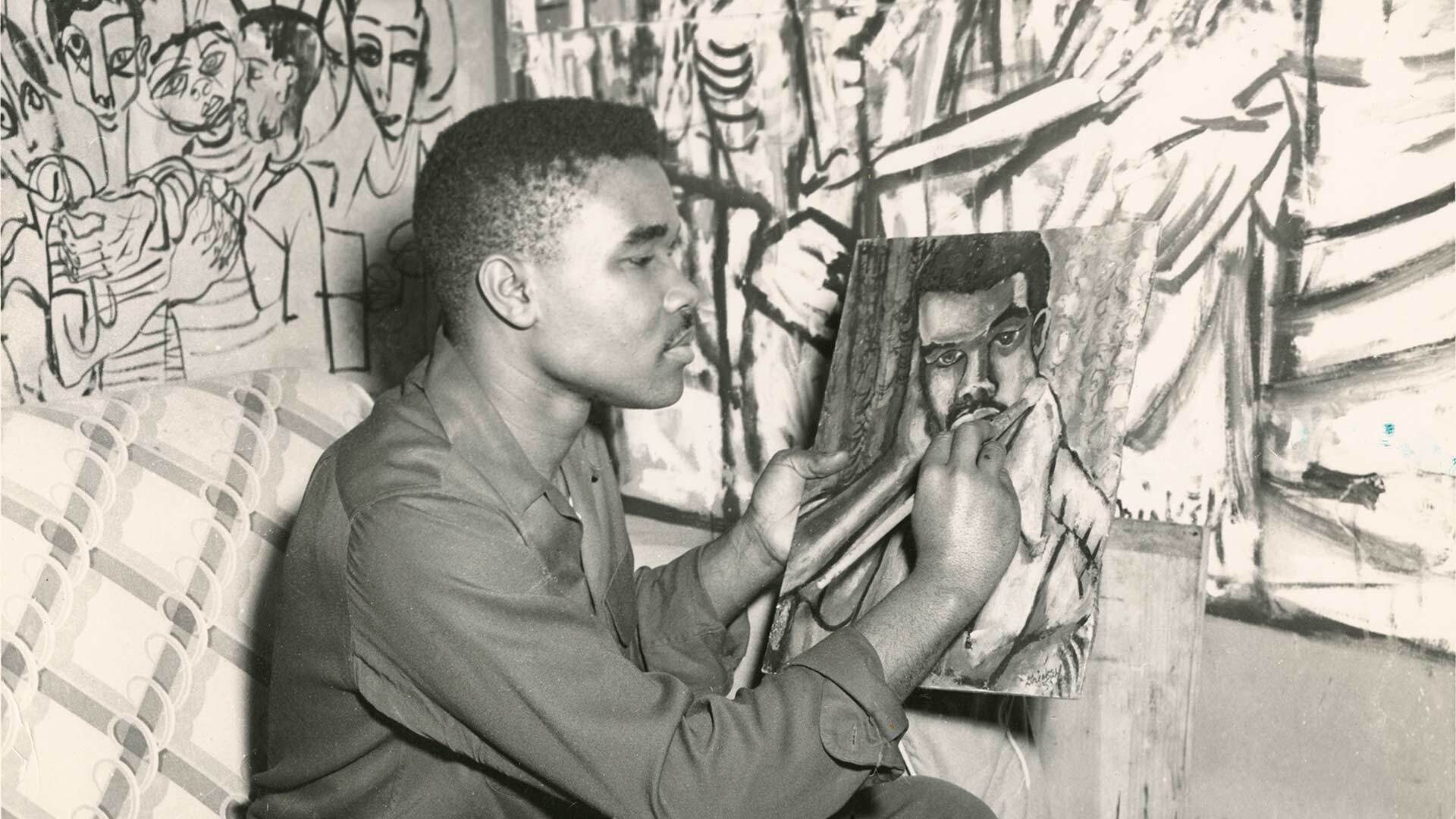

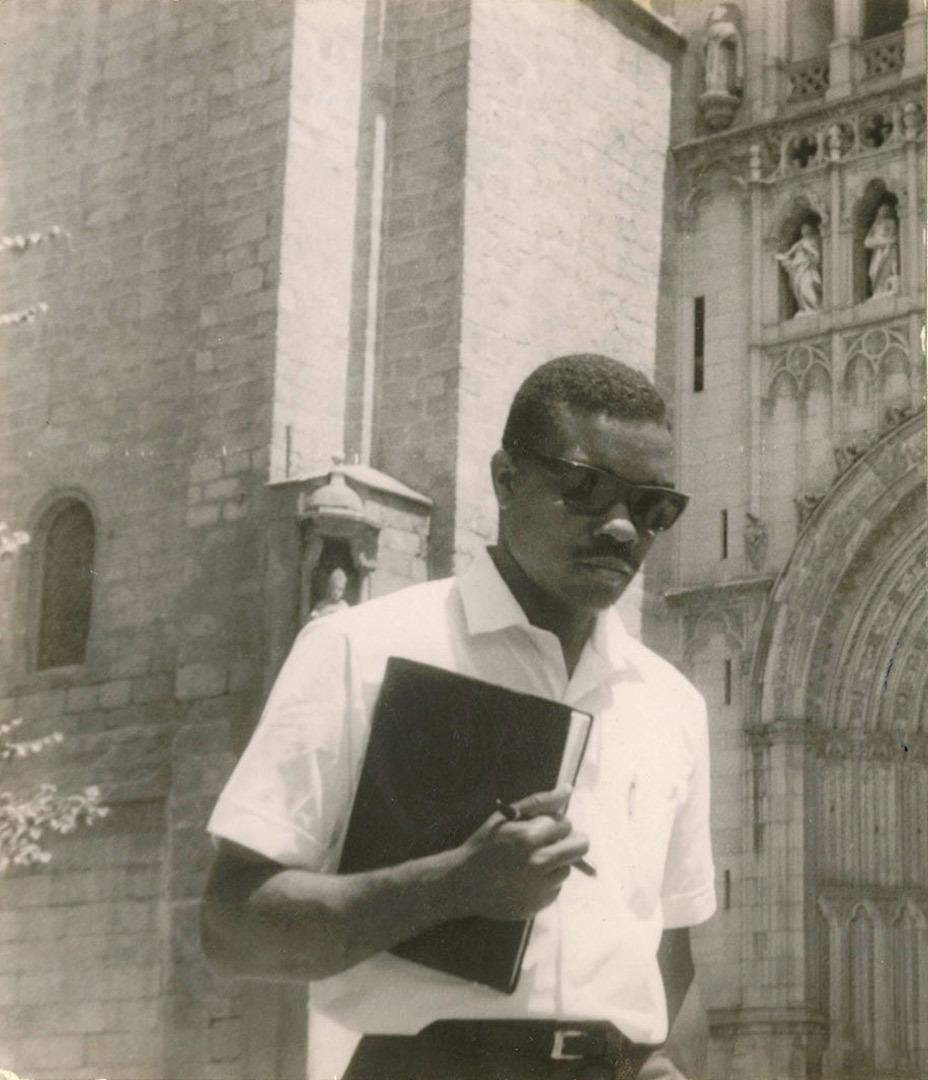

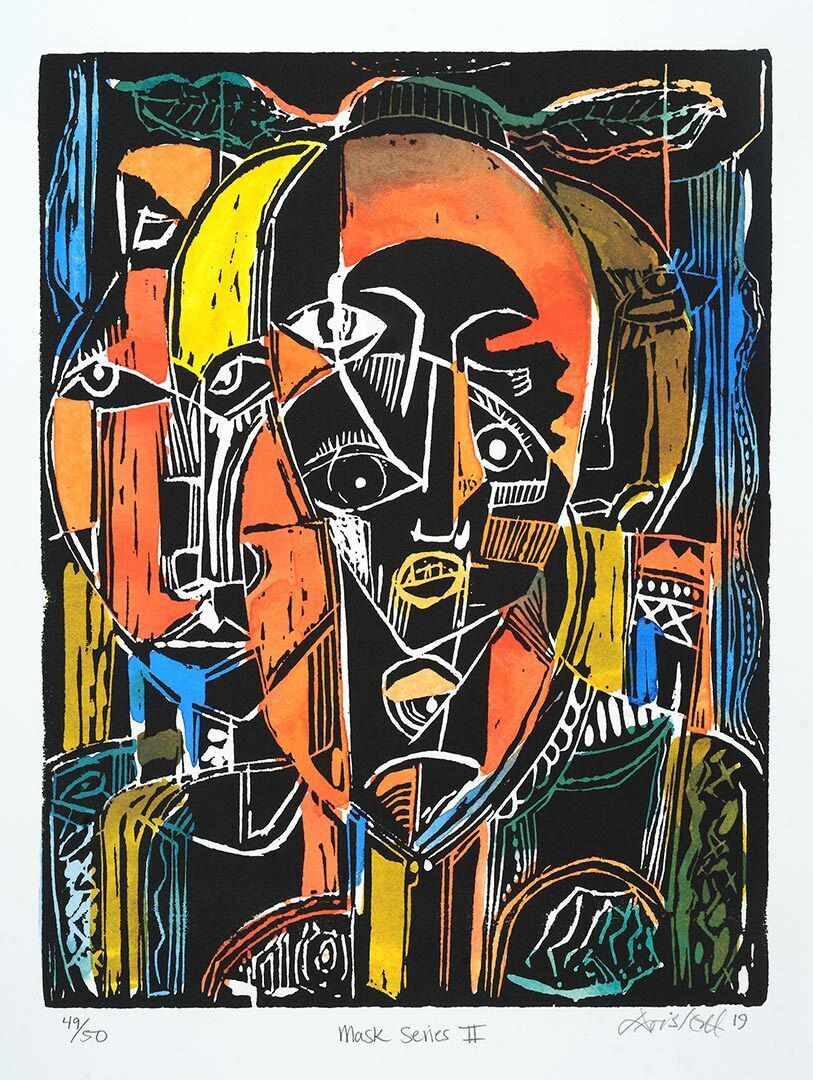

The exhibit, opening today, culls 110 items from the collection of 50,000-plus documents dating to the 1950s that he and his wife, Thelma Grace Driskell, had donated to the center. Divided into “galleries” by decade, they include lecture notes, student dissertations, slides from his exhibitions, journal entries and correspondence with other major artists. Images of Driskell’s artwork appear as well.

“'The David C. Driskell Papers' reveal processes which Professor Driskell used to establish the intellectual foundation of the study of the artistic production of African American artists,” said Curlee Raven Holton, executive director of the Driskell Center. “These artists, often in the shadows of our collective history, were brought into the foreground and illuminated by Professor Driskell's research and promotion.”

The exhibit takes visitors on a tour of people and places critical to Driskell’s own development, from his studio in Falmouth, Maine, to his home in Nashville to Talladega College in Alabama, where he had his first teaching position.

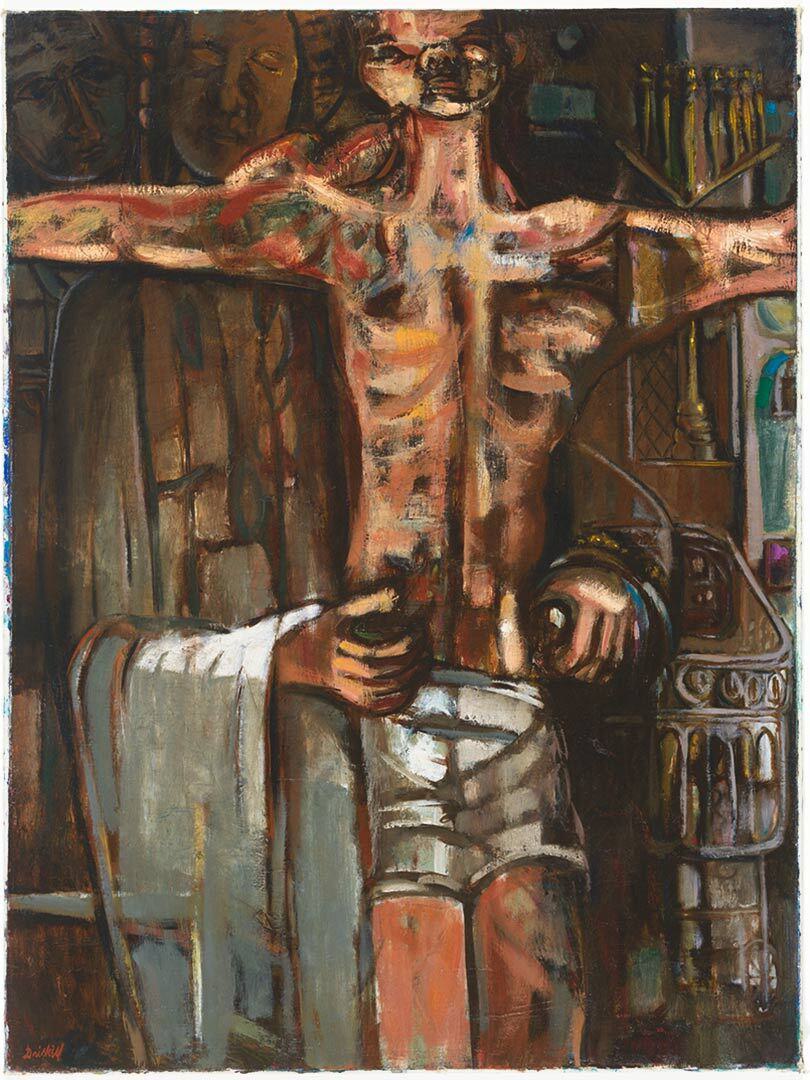

From the time Driskell painted his best-known work, “Behold Thy Son,” a 1956 meditation on the racist murder a year earlier of teenaged Emmett Till that takes the form of a pietà—a traditional depiction of Mary holding Jesus’ body—he stood against the conception of African American art as cut off from the mainstream.

“He was charged with a special task—go forth and promote African American artistic work in a way the world may not be ready for yet,” Holton said.

Driskell arrived at Maryland in 1977, a year after his groundbreaking exhibition, “Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950.” His own works are held by museums such as the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the National Gallery of Art and the Phillips Collection.

Other events include a Sept. 17 symposium in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, as well as a panel discussion on Driskell’s legacy. In Spring 2021, the center will present an exhibition focusing on the work of his students, many of whom went on to successful careers themselves.

“He was a trailblazer,” said acclaimed performance artist Jefferson Pinder ’93, MFA ’03, who studied with Driskell at Maryland. “So many people are indebted to the work he’s done.”

Topics

Arts & CultureTags

Visual Arts