- November 21, 2022

- By Maggie Haslam

This story has been updated to reflect NASA's revised launch schedule.

Despite its infinite reach, real estate in outer space is a precious commodity.

Nowhere is that more apparent than within the tiny plastic tube, roughly the size of a Magic Marker, that a group of four University of Maryland students filled with silicon and iron oxide in preparation for a 420-kilometer trip skyward scheduled for Saturday afternoon from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center.

They hope that, once closer to the stars, their miniature laboratory—the fifth unique student experiment to take place aboard the International Space Station (ISS) as part of the Terps in Space program—offers insight into how planets form. It’s an experience that’s truly out of this world: the chance to design an experiment, write a compelling proposal, and vie for the chance to have astronauts floating in weightlessness watch over your work.

A legion of UMD staff, faculty and graduate student mentors work with undergraduates in the program, led by senior faculty specialist Daniel Serrano M.S. ’10, Ph.D. ’14. It was his original pitch that allowed Maryland to become one of a handful of universities to participate in the National Center for Earth and Space Science Education’s Student Spaceflight Experiments Program.

Space missions—even pint-sized ones—come with a hefty price tag: Sending one experiment costs $25,000 before materials and personnel. Serrano works with external sources, as well as departments and schools on campus, to secure funding each year for Terps in Space.

“The behind-the-scenes administration and mentorship is critical for this to even happen,” said Serrano, who works for UMD’s Institute for Physical Science and Technology. “Many of those same volunteer faculty who were with me on that first review in the basement of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum come back and make this possible, year after year.”

The Terps in Space program has grown a dedicated following, with many participants returning after graduation to assist with logistics and provide student support. Jason Hipkins ’21, who took part as an undergraduate and now advises for both Terps in Space and Maryland’s Students for the Exploration and Development of Space chapter, said the experience rivals any you can get at Maryland: an extracurricular activity that’s inclusive and interdisciplinary, and that also offers a foray into research at a pivotal time.

“If you’re a curious person, programs like Terps in Space are a really valuable experience and a great introduction to research,” Hipkins said. “It’s fundamental to advancing UMD’s activities as a research institution. I would attribute Terps in Space as one of the reasons I stuck with research.”

While sending an experiment to space is resume gold, what keeps Serrano running the program is the bevy of skills students gain before the rocket is launched. Writing, teamwork, critical thinking, planning, communication and even fundraising (teams are responsible for their own materials) are skills both integral to Terps in Space, and alien to the typical undergraduate project.

“It’s the real deal,” said Serrano. “The vision of the program is to expose students to the full spectrum of the scientific profession in a condensed period. Terps in Space is an opportunity for students to gain skills that aren’t conventional for an undergraduate experience, but that will really resonate as they begin their professional journey.”

This story originally appeared in Engineering at Maryland magazine.

An Inside Look at this Year’s Space-Bound Experiment

Team Obsidian beat out 10 other Maryland teams for a spot aboard the ISS flight scheduled for takeoff Saturday.

The experiment, developed by students Vincent Lan (materials science and engineering), Brian Sun (mechanical engineering), Adrian Seemangal (geospatial information science) and Joseph Niba (mathematics)—with the help of graduate student mentors Michael Kio (chemical and biomolecular engineering) and Anmol Sikka (aerospace engineering)—aims to better understand the mechanisms of planet formation by exploring how small particles of dust coalesce.

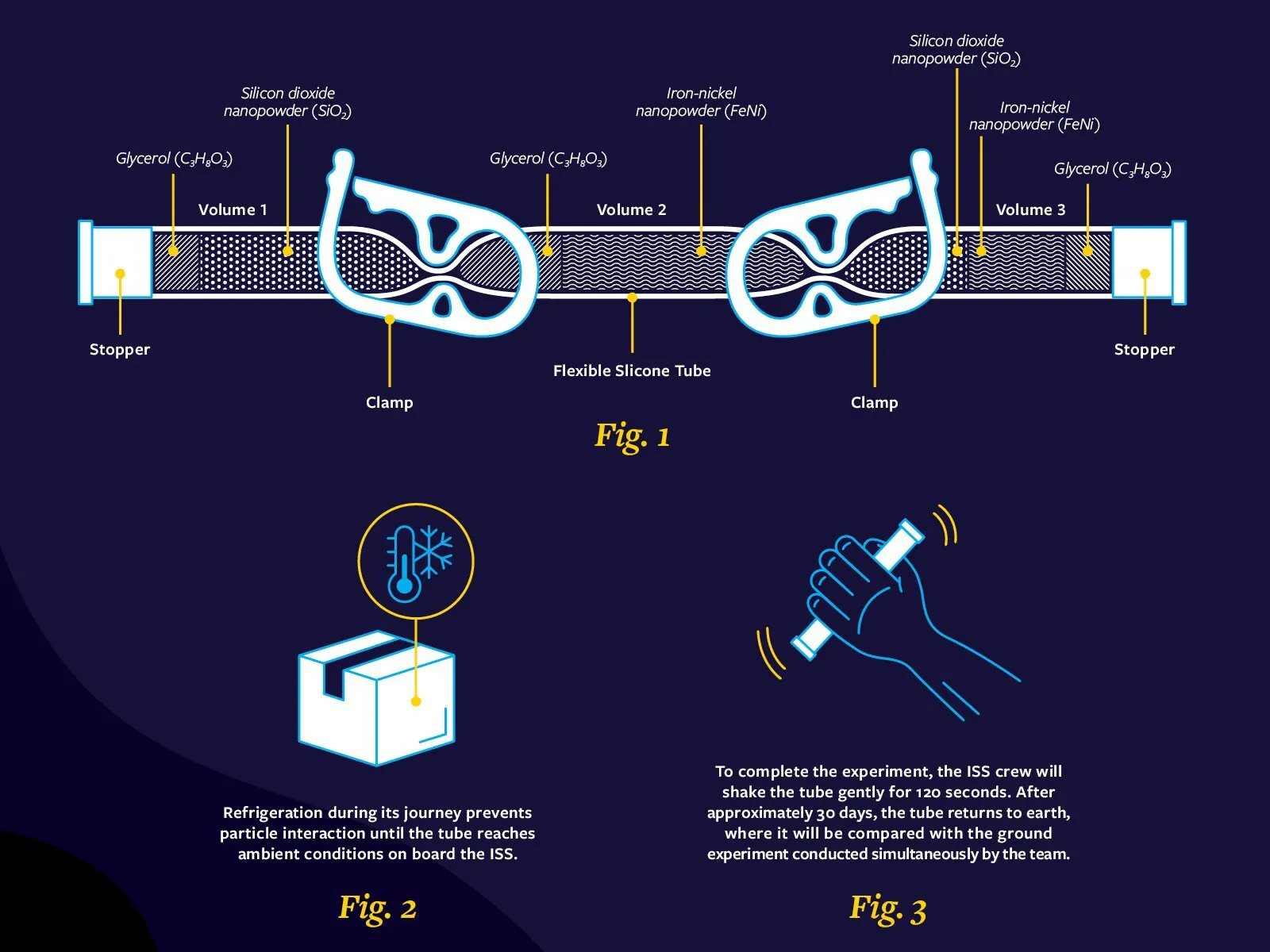

The experiment capsule offers flexibility, including the ability to separate materials. Team Obsidian will put a mix of silicon dioxide nanopowder and glycerol on one side and a mix of iron oxide and glycerol on the other (see graphic), which astronauts will later mix on board the ISS.