- September 22, 2015

- By Karen Shih ’09

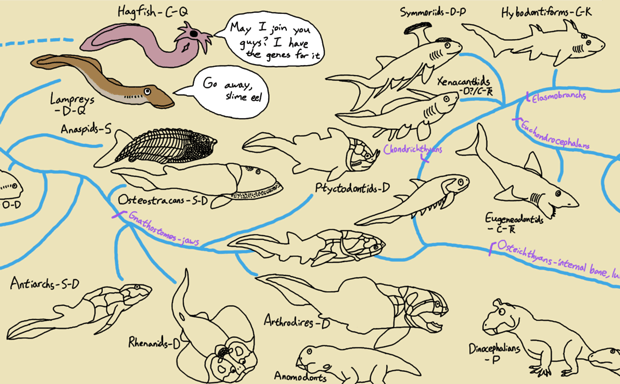

If you already know that pterosaurs aren’t actually dinosaurs, or that humans are more closely related to bunnies than bears, or that our beloved Testudo—and his fellow turtles—have never had a fixed place on the great tree of evolution, this map isn’t for you.

But for the rest of us, this whimsical cartoon drawn by Albert Chen ’16 is a fun ride through 520 million years of vertebrate evolution. Despite his lack of formal art education, he was inspired by his spring vertebrate paleobiology class to create a condensed version of the massive study guide he created for his peers. It took him about a month to outline and draw it, and it’s since been tweeted by many scientists and picked up by places like the National Center for Science Education.

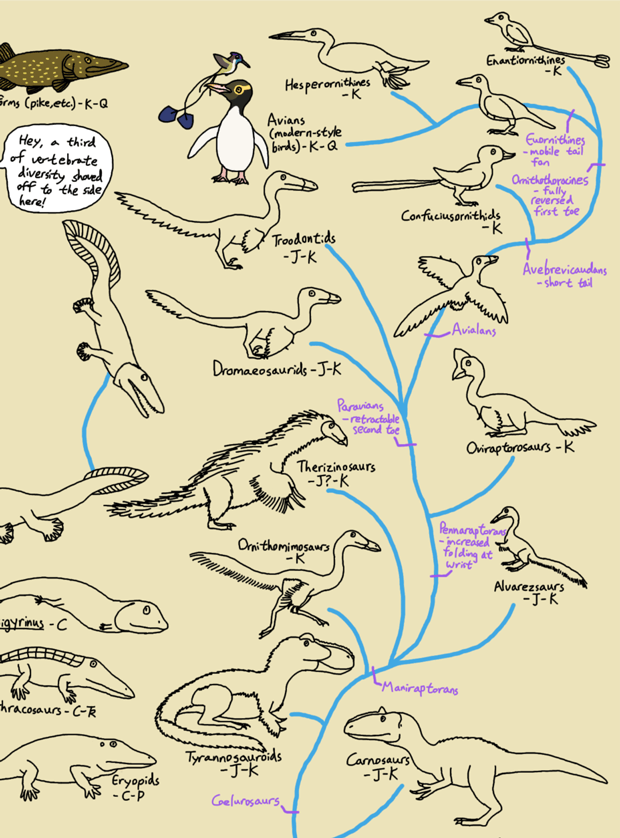

“I’m glad it’s proven to be so popular,” says Chen, who plans to study paleontology in graduate school. “In that respect, I’m kind of a clichéd guy. I like dinosaurs. I especially like the smaller dinosaurs, a group called alvarezsaurs—think the size of a pigeon up to the size of an emu. What’s really weird about them is that they had really short forelimbs. We make fun of T. rex, but these guys basically had only one finger on each hand, like spiked thumbs.”

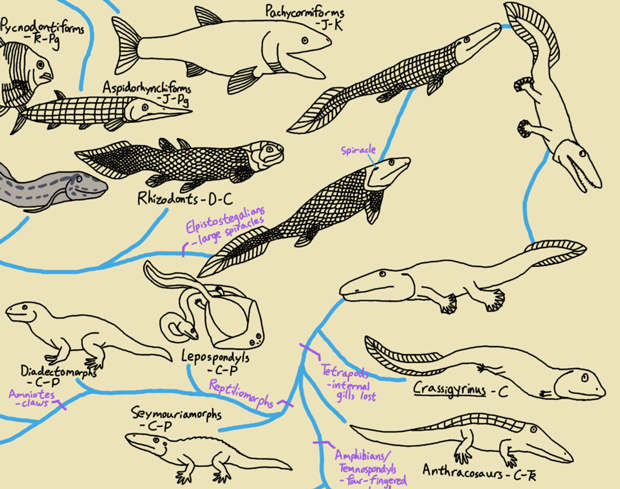

His map extends from the earliest, boneless beings to today’s penguins and rhinos (though he warns it’s not to scale). Chen takes us on a tour through the tree:

Jaws, Bones and Lungs

Those were first three major milestones our ancestors hit in the earliest days. Jaws conferred the important ability to bite things—some early vertebrates, like modern-day lampreys, had only suckers to scrape things into their mouths, while others swam through the water with their mouths open and filtered plankton. Bones started on the outside of fish, as armor, before becoming skeletons inside. Though the idea of lungs in fish sounds weird, many fish, like the invasive snakeheads, still use them in addition to gills.

Out of the Water

Eventually, of course, our early ancestors had to make their way onto land. This led to the development of fingers and toes and limbs with elbows, ankles and wrists. “Our last ties to the water were in terms of reproduction,” Chen says. Amphibians, for example, still reproduce in water. Hard-shelled eggs were the start of fully land-based life.

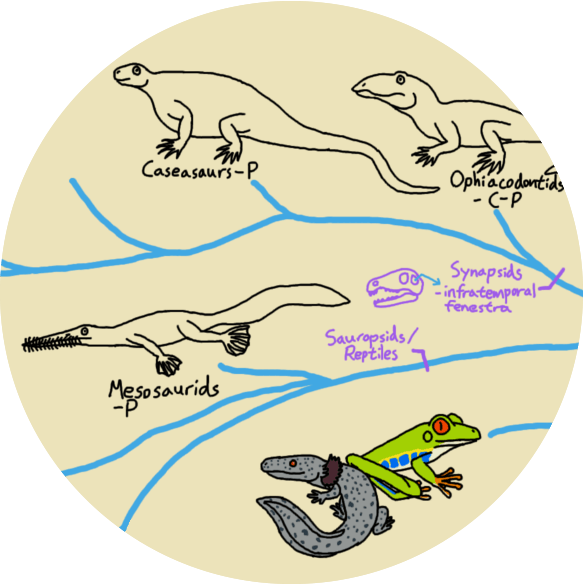

Two Major Branches

At this point, vertebrates split into reptiles and the group that would become mammals. In modern-day vertebrates, they can be distinguished by holes in the skulls behind their eyes; reptiles are diapsids, which have two, and mammals are synapsids, which have one.

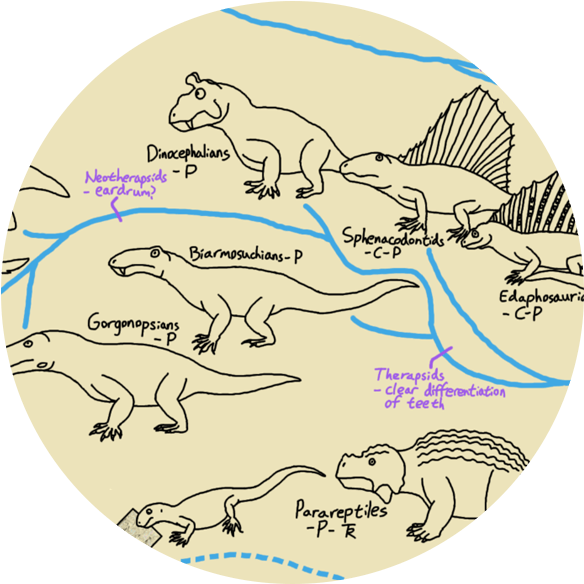

Creative Chompers

Unlike most vertebrates, mammals developed specialized teeth. “In crocodiles, all the teeth are basically the same size and shape, and in fish, sharks are famous for changing their teeth throughout their lifetime,” Chen says. But mammals and our ancestors have differentiated teeth like incisors, canines and molars and change just once throughout our lifetimes. “That’s why dentists make money.”

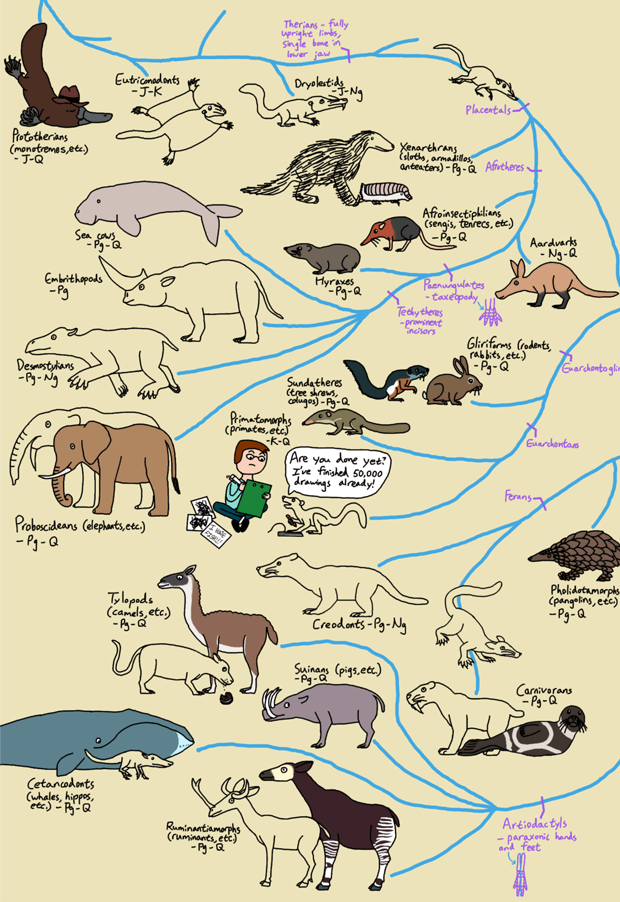

Mammal Family

For about 70 percent of mammal history, they scurried in the shadows of the dinosaurs and reptiles that ruled the land. It wasn’t until after the major dinosaur extinction that they started growing larger. Today, most living mammals (except marsupials and monotremes) fall into four major groups. The first includes armadillos, sloths and anteaters; the second includes sea cows, elephants and hyraxes; the third includes primates and therefore humans along with rodents; and the fourth includes all hooved animals, cats and dogs, and even whales. (Bats are mammals, but the dotted line means scientists are still unsure about where in the tree they belong.)

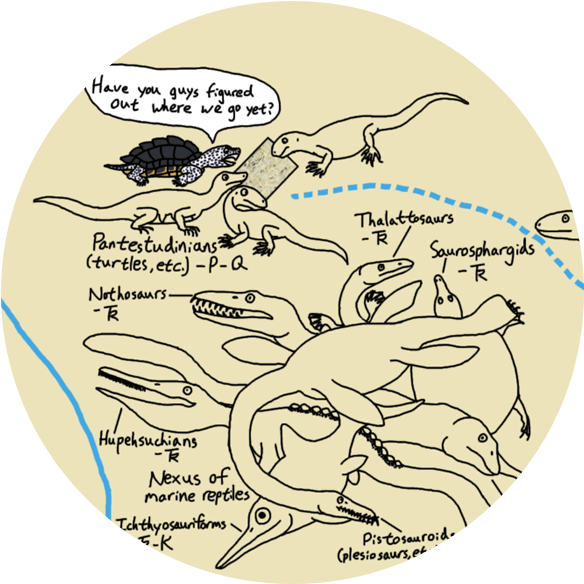

Diapsid Conundrums

These dotted lines represent two mysteries: the tangle of large sea creatures from the dinosaur era that don’t yet have a clear connection to the rest of the tree, and Testudo and his fellow turtles. “Turtles are the weirdest vertebrates you can come up with,” says Chen. “It would only be a minor exaggeration to say you could start a fistfight at a paleontology conference if you asked where turtles are [on the tree].” Only this year have scientists discovered the first good fossil evidence that turtle ancestors did have two holes in their skulls, which would place them in the diapsid family.

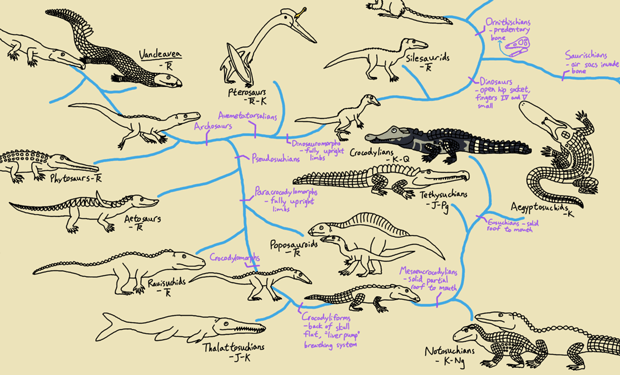

Crocs, Then and Now

Relatives of crocodiles were the largest animals predators on land before the rise of dinosaurs. During the dinosaur era, there were armored plant-eating crocodiles, little rat-like crocodiles that ate insects, bipedal crocodiles that had beaks, not teeth, and fully marine crocodiles.

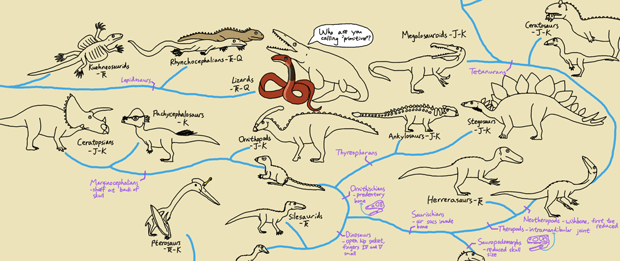

Dino Differences

Let’s start with what’s not a dinosaur—the pterosaur to the left. Their long “ring fingers” support their famous wings—and dinosaurs are defined by their small, stubby ring and pinky fingers. Within dinosaurs are two major groups: One includes most of the plant eaters, including stegosaurus, ankylosaurs and Triceratops. The other includes some plant eaters like the Brontosaurus, but is most famous for the meat eaters.

Fear the Feathers

If you heard anything about the controversy over the summer blockbuster “Jurassic World,” you know that scaly, gray versions of Velociraptors and T. rex are out—and feathered, fuzzy meat-eaters are in. “Evolution is complicated,” says Chen, whose favorite alvarezsaurs, including the Albertonykus, his online avatar, are in this group. “If they were alive today, we’d say, ‘That’s a funny-looking bird over there.’… We joke that penguins are the pinnacle of dinosaur evolution—not only did they go back to the water, they went back to not flying!”