- January 05, 2016

- By Karen Shih ’09

While scientists, environmentalists and public officials push to reduce gas guzzling through electric cars, biofuels and HOV lanes, one ideal transportation option surfaced more than a century ago.

Bicycles took the country by storm in the 1890s, when they were fine-tuned and mass-produced for the first time. They spread from the rich upper class, who raced through parks for sport, to the working class, who pedaled to jobs across the city; they even gave new freedoms to women and minorities, finally able to travel by their own means. Streets evolved accordingly. No longer did rotting carcasses and horse droppings create hazards on dirt roads; cyclists banded together to demand paved, marked thoroughfares that would become commonplace throughout the country.

Bicycles took the country by storm in the 1890s, when they were fine-tuned and mass-produced for the first time. They spread from the rich upper class, who raced through parks for sport, to the working class, who pedaled to jobs across the city; they even gave new freedoms to women and minorities, finally able to travel by their own means. Streets evolved accordingly. No longer did rotting carcasses and horse droppings create hazards on dirt roads; cyclists banded together to demand paved, marked thoroughfares that would become commonplace throughout the country.

In his new book, “The Cycling City,” Evan Friss ’02, an assistant professor of history at James Madison University, explores the monumental changes bicycles brought during that decade, why their popularity flamed out as quickly and what today’s transportation planners can learn from that time, as bike shares and bike lanes help cyclists reclaim their place on our streets.

TERP: Why study the history of bicycles?

Friss: People think that there’s some sort of cultural history, that Americans are just car people and it’s always been that way. I’m suggesting that it wasn’t so long ago when Americans were more bicycle-crazy than any other country in the world, when people in D.C. were cycling more than people in Amsterdam and Copenhagen, which we look at as models of the cycling city today.

In the 1890s, people were taking bicycles very seriously as the future of America. Lots of people were thinking deeply and seriously about planning for a cycling city. This new device for personal, private transportation would, they hoped, reorder American life. In this relatively short period of time, cyclists coalesced into this loud group of political activists and people you’d see on the street in great numbers.

TERP: What were some of the lasting changes from that era?

Friss: The big thing that cyclists did was set the table for the motorists to follow, not only the infrastructure and paving roads, but in terms of advocating for comprehensive traffic law. Bicycles really helped bring some thinking about, “How do we create order on the streets?”

Even though cyclists largely disappeared, they managed to create these powerful interest groups that were a model for the Automobile Association of America. In many ways the leaders of the bicycle industry became leaders of the automobile industry. Promotional bike shows, lobbying—these migrated to automobiles and set the precedent of many of the things that take off to the nth degree with cars. There were also more subtle social changes for women that were complex and very long term.

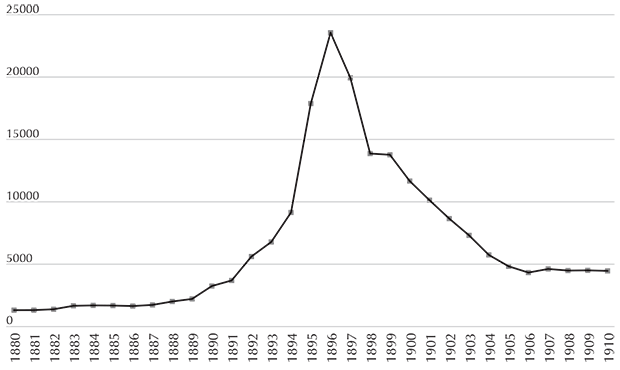

TERP: With bicycle production rising so rapidly—from fewer than 50,000 in 1890 to nearly 1.2 million in 1898—why did bicycles fall so abruptly out of favor at the turn of the century?

Friss: At first it was a novelty item, then it became something that wealthy people are attracted to, then trickles down to the middle class. At the end of the 1890s, the working classes are riding as well, so it undergoes a great deal of change in terms of its ridership. Riding was no longer a means to assert one’s wealth and class. Early adopters tend to be these hyper masculine young men of means, who see it as this masculine endeavor. But when it enters the mainstream and has the potential to transform cities more, they lose interest. There’s an irony there.

TERP: Why do you think bikes are experiencing a resurgence today?

Friss: One of the most interesting things about the bicycle is that, even though it has gone through these booms and waves and peaks and valleys, it hasn’t disappeared like the horse that came before it, or streetcars, which mostly disappeared. The bicycle looks more or less the same as it did in the 1890s, but it’s still found in cities even as its purpose and use change over time. There’s this kind of affinity that many people have to move through the city on their own power.

TERP: Do you think this means bicycles will become an integral part of our transportation options, going forward?

Friss: Historians are notoriously bad at predicting the future. Part of the hurdles of bicycles coming back is the many years of lack of planning for bicycle infrastructure. There are gains being made, like with Capital Bikeshare, which are great but still relatively modest. I’m suspicious that this is the beginning of a great transformation, as much as I would like it to be.

What cities really need to do is as they’re redoing roads and repaving roads, add bike lanes as a normal institutional process. Advocates shouldn’t need to always be championing revolutionary ideas; it should be embedded in urban infrastructure. One day, I hope, we’ll get to the point where adding a bike lane is just as boring as striping a street for automobiles.