- August 18, 2016

- By Karen Shih ’09

ichelle singletary ’84 once froze the half-eaten sheet cake from her husband’s birthday, preserving the part in the middle with her husband and son’s shared name. Then she served the shrunken version a month later—at her 4-year-old son’s party.

ichelle singletary ’84 once froze the half-eaten sheet cake from her husband’s birthday, preserving the part in the middle with her husband and son’s shared name. Then she served the shrunken version a month later—at her 4-year-old son’s party.

She’s not embarrassed about that. Or about delving deep into her fiance’s finances before they got married. Or re-wrapping toys from the bottom of the toy bin for her young kids at Christmas.

Why should she be? Singletary spent the first four years of her life hungry and neglected by her birth parents, before being taken in by her grandmother, a nurse’s assistant who never made more than $13,000 a year. There, she had exactly what she needed and not much more—not an extra pair of sneakers from the grocery store bin for school or another serving of fried chicken and pinto beans at dinnertime.

“Frugality is a way to keep control,” she says. “Financial security means you have choices. Things don’t happen to you. If your car breaks down, it’s not a catastrophe.”

That’s the message she sends as the syndicated columnist of “The Color of Money” at The Washington Post; through her three books, radio interviews and television appearances, including her own cable show; and in her work in the community with husband Kevin McIntyre ’84 through their Prosperity Partners financial ministry program.

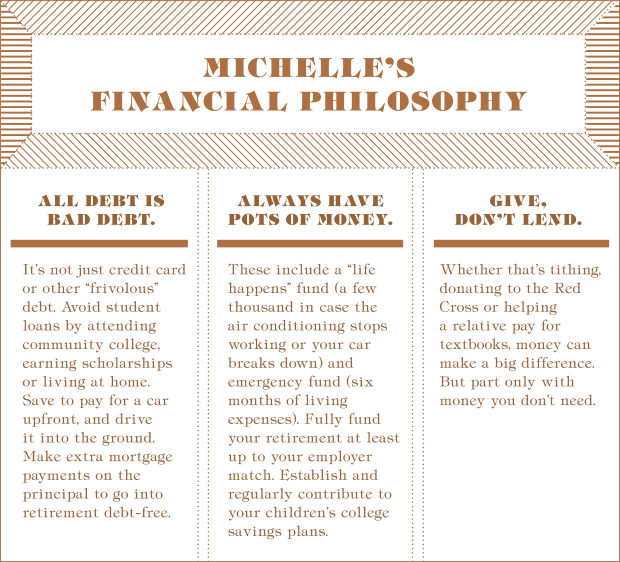

Her no-nonsense, Bible-inspired advice and strong opinions on personal finance include a hatred of debt, an emphasis on giving and an insistence that married couples share everything financially. Some call her approach simplistic and too uncompromising—but the thousands she’s helped say she changed their lives.

“Personal finance is rocket science these days,” Singletary says, citing retirement accounts, life insurance, college funds, identity theft and credit card fraud. “I understand why people make bad financial decisions.”

ven a casual Singletary fan knows all about “Big Mama,” her late grandmother, who always paid her bills early and retired with her mortgage paid off.

ven a casual Singletary fan knows all about “Big Mama,” her late grandmother, who always paid her bills early and retired with her mortgage paid off.

She brought stability to Singletary and her four siblings, aged 1 to 8 at the time she took them in. At her immaculate West Baltimore rowhouse, they got regular meals, school supplies and clothes.

While “kids would tease us about the stuff we had,” she says, recalling a jingle about $1.99 “fish head” sneakers people used to sing at her, “We knew it was tight for her. You didn’t complain… and she never apologized for it.”

Her grandmother refused nearly all welfare, instead carefully budgeting to cover the children’s needs. The only exception was medical aid to treat their serious ailments, including asthma, epilepsy and Singletary’s juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. (It forced Singletary out of school for three years, during which she took classes over the phone. Her condition improved significantly as she got older.)

Her grandmother refused nearly all welfare, instead carefully budgeting to cover the children’s needs. The only exception was medical aid to treat their serious ailments, including asthma, epilepsy and Singletary’s juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. (It forced Singletary out of school for three years, during which she took classes over the phone. Her condition improved significantly as she got older.)

But Big Mama’s distrust of government assistance brought Singletary to tears when she was accepted to the University of Maryland and needed help paying for college.

“I am not sharing my information with these people,” her grandmother said, refusing to fill out the forms. “They’ll come take my house.”

For Singletary, college was an opportunity to not only escape poverty but also eventually help her family financially.

Luckily, The Baltimore Sun newspapers introduced a minority scholarship her senior year in high school that not only covered tuition, room and board and books, but also included four paid summer internships and a job after graduation.

At the insistence of her grandmother, Singletary set out alone at 6 a.m. for her

10 a.m. interview to catch a bus to the newspaper office downtown. Even after waiting in the lobby for nearly four hours, she charmed the editors with tales of growing up with Big Mama’s endless rules.

“They were just rolling with laughter,” she says. “Years later, one of the editors on the committee said to me, ‘You were so confident, coming from so little.’”

ingletary easily admits she lived at UMD like an “80-year-old Depression-era woman,” with a 10 p.m. bedtime, Sundays at church and virtually no partying (“I’m not paying $5 for a drink!” she recalls saying indignantly)—nothing that would put her scholarship at risk. In addition to becoming the first female president of the Black Student Union, she also worked at The Diamondback, The Black Explosion, The Baltimore Sun and The Evening Sun.

ingletary easily admits she lived at UMD like an “80-year-old Depression-era woman,” with a 10 p.m. bedtime, Sundays at church and virtually no partying (“I’m not paying $5 for a drink!” she recalls saying indignantly)—nothing that would put her scholarship at risk. In addition to becoming the first female president of the Black Student Union, she also worked at The Diamondback, The Black Explosion, The Baltimore Sun and The Evening Sun.

As a rookie Evening Sun reporter, she covered cops, fires and zoning before moving to religion, then bankruptcy. Her story about former Baltimore Colts quarterback Johnny Unitas going broke caught the attention of The Washington Post, which hired her in 1992 to cover business. Her ability to turn dry, complicated topics into interesting stories, combined with her frugal habits like bringing lunch every day (that inevitably led to tales about Big Mama), intrigued her editors, one of whom eventually offered her a column.

In the days after the column’s debut, bags of mail arrived in the newsroom, along with hundreds of emails—completely unexpected back in 1997. Readers long intimidated by the business section finally felt like someone was talking to them.

The Washington Post Writers Group syndicated “The Color of Money” a little over a year later. Today, the twice-weekly column runs in about 100 newspapers across the country.

She can’t answer the dozens of emails she gets each week, but she responds to as many questions as possible during weekly online chats. During these “Testimony Thursdays,” she celebrates those who have paid off crushing loans and high-interest credit card debt, and doles out encouragement and advice to those who haven’t figured it all out. Sometimes, she even nudges overly frugal readers to spend the money they’ve saved on heated leather seats or a tropical vacation.

nmates at the Central Maryland Correctional Facility roll their eyes and groan when Singletary tells them to cut their spending at the commissary in half. That means two weeks without snack cakes or instant ramen to supplement the “goop” they’re served at each meal.

nmates at the Central Maryland Correctional Facility roll their eyes and groan when Singletary tells them to cut their spending at the commissary in half. That means two weeks without snack cakes or instant ramen to supplement the “goop” they’re served at each meal.

The 20 men in the makeshift classroom need better financial habits to avoid returning to crime to make a living, she says. A few argue, but one shouts out, “Free food always tastes good to me!”

“That’s my man!” she says, high-fiving him.

She shushes and shouts, teases and cajoles, but she doesn’t back down—not with inmates, and not with fellow parishioners of First Baptist Church of Glenarden. That’s where in 2005 she created Prosperity Partners Ministry, a yearlong program modeled after Alcoholics Anonymous that attracts 150 to 200 participants annually (including many from outside the church). She and her husband teach monthly sessions on budgeting, money management for kids and investing basics and coach those who are good with their money to be mentors to the financially challenged.

Though Singletary started out solo, they always work together now. McIntyre and she are on the same financial wavelength—he wooed her in college with entire meals cooked in a toaster oven—and he’s gracious about sacrificing his days off to volunteer at the prison with her. He also brings balance to their sessions. While she sings Michael Jackson hits, plays “musical bills” (musical chairs with each chair representing a bill) and does her own version of “Judge Judy,” he provides the calm voice that steadies those who are overwhelmed.

Church member Trinita McCall and her husband endured Singletary’s “financial fast”—21 days of buying only absolute necessities, such as food and medicine, in cash—even as she called the experience “horrible.” But it helped the couple end years of reckless spending without a budget, overdrafting their bank account and charging up credit cards. Today McCall is a leader in the ministry and volunteers with Prosperity Partners.

“I had one junior partner who would literally call me in the line at Wal-Mart with a cart full of things so I could talk her down,” McCall says. “A different partner had a box of bills she had never opened. We’re helping people face the reality they’re in.”

ontrary to most parents, Singletary says, “I don’t want my kids to have it better than me. The way I lived taught me to appreciate what I have.”

ontrary to most parents, Singletary says, “I don’t want my kids to have it better than me. The way I lived taught me to appreciate what I have.”

Her three children, ages 15, 18 and 21, do have it better, of course: They live in a nearly 5,000-square-foot home in Bowie, Md., go on a two-week resort vacation each year and have fully funded 529 plans for college.

That doesn’t mean they always appreciated those luxuries when they couldn’t get the newest toys or trendiest outfits. Monique ’17, a family science and psychology double major at UMD, recalls Singletary refusing her a new pair of pants, telling her to roll up ones that were too short and pretend they were capris.

“It was so frustrating to be told all the time, ‘Do you have money for that?’ I’m young, you’re my mom, just get it for me!” she says.

These days, Singletary doesn’t begrudge them the rare name-brand item like an iPad Mini or a North Face jacket when they work for it—though today they rarely ask, and it’s a given that they’ll tithe and put money into savings first.

It’s clear her lessons have stuck.

“I just had a big epiphany that I am exactly like my mother. I am Michelle 2.0,” says Monique. “When I was growing up, in my head, I’d hear my mom’s voice saying, ‘Is that a need or a want?’ Now, I don’t hear her voice anymore. It’s just my voice: ‘Girl, you don’t need that.’” TERP