- May 06, 2015

- By Karen Shih ’09

In the mountains of Western Maryland, a world away from the Chesapeake Bay that dominates so much of the state’s industry and culture, is a man on a mission to change Maryland’s signature drink.

Lowbrow Natty Boh beer paired with bushels of blue crabs or chugged at a local bar? Forget it.

Joe Fiola Ph.D. ’86 wants you to drink Maryland wine.

But you might think: Does Maryland even make wine? (Yes, in every county.) Is it any good? (It wins gold medals.) Why should I try it? (To save the environmental costs of shipping your preferred Australian or French wine, and to make good on that locavore pledge.)

“We can compete with anyone in the world,” says Fiola, principal agent and extension specialist at the Western Maryland Research and Education Center (WMREC). “Taste the wines. There’s the proof.”

Despite having a similar climate and latitude as traditional wine producers like Spain, Italy and France, Maryland never had much of an industry. In 1662, Gov. Charles Calvert planted 200 acres of European grapes along the St. Mary’s River, only to see the vines wither within a few years. It wasn’t until nearly 300 years later that Boordy Vineyards opened in Baltimore County.

What held grape growers back? A combination of archaic laws, dating back to Prohibition; lack of interest and support from the state government; the dominance of crops like tobacco and corn; and a dearth of knowledge about the types of grapes that could be grown in the state’s four distinct growing regions, ranging from cooler, dry mountains in Western Maryland to the wet, flat plains of the Eastern Shore. Local wine also suffered the reputation of being sweet, since inexperienced winemakers tended to add sugar to compensate for varietal shortcomings.

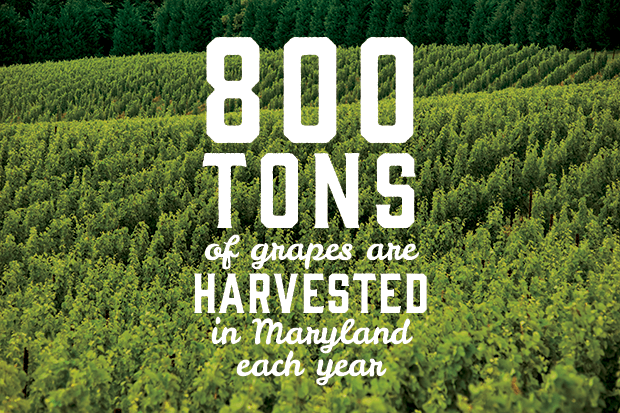

But since he arrived in 2001, Fiola (below) has helped Maryland’s wine industry expand dramatically, from just 11 wineries to close to 70 today, and from 450,000 bottles to more than 1.7 million sold in 2013.

“The quality has just exploded since 2000,” says Dave McIntyre, wine columnist for The Washington Post. “People have learned how to get the grapes riper, and that makes the wines better, and that’s why you see really good improvement almost across the board.”

That’s thanks in part to Fiola’s research on every aspect of grape growing and wine production, from the introduction of new varieties and improved methods of pest control to the development of detailed site maps. He’s guided a new generation of vineyard and winery owners throughout the state—and now, he’s ready for Maryland wine to crush the competition.

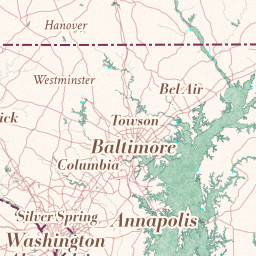

Click on map to see Terp-owned vineyards and wineries throughout Maryland.

Learning to Grow

In 1960s South Philadelphia, where the only neighborhood greenery was the rare tree or two and the weeds sprouting through sidewalk cracks, young Joe Fiola found an oasis in his grandparents’ backyard.

There was a fig tree from which he’d pluck ripe fruit throughout the summer; basil and tomatoes that formed the base of his family’s homemade pasta dinners each Sunday night; and even a sprawling grapevine. He hovered over simmering sauces in his grandmother’s kitchen, marveling at how the ingredients came together for their meals—served, of course, with wine.

That’s what inspired him to dig up a corner of his family’s quarter-acre backyard when they moved to New Jersey when he was 12, creating a garden with tomatoes, radishes, peppers, raspberries and strawberries.

“It was such a satisfying feeling, to plant a seed or a plant, get a good harvest… then watch my mom cook,” Fiola says.

He pursued that interest at Rutgers, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in plant and agricultural sciences. He came to UMD for his doctorate, but after graduating, he returned to Rutgers Cooperative Extension to work as a small fruit specialist, breeding hardier, better-tasting fruits and earning a dozen patents. Traditionally, “small fruits” focused on blueberries, strawberries and raspberries, but he added grapes to the mix, and by the time he left in 2001, he had helped grow the number of New Jersey wineries from 13 to nearly 50.

Researchers in Maryland noted his successes, and hoping to play catch-up with Virginia’s burgeoning wine industry, the UMD Extension recruited Fiola back to the state.

“We were lucky to snag him,” says Kevin Atticks, executive director of the Maryland Wineries Association.

Fiola often talks of being “blessed,” and in many ways, his return to Maryland seemed preordained. While he was working at Rutgers, his UMD adviser asked him to help set up vines at WMREC in Keedysville to study clones and disease control. He also planted some Eastern European varieties on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, to see how they fared in the sandy soil. Finally, he was asked to help extension agents in Southern Maryland create a variety trial to determine what grapes could grow best in a challenging region that was looking for a new industry after tobacco buyouts. When he got the offer from Maryland, he already had grape research going in every corner of the state.

Good Grapes, Winning Wine

“You don’t realize it, but there are thousands of varieties of grapes,” says William Layton ’96, owner of Layton’s Chance Vineyard and Winery on the Eastern Shore, who started with four hardy, easy-to-grow varieties recommended by Fiola: chambourcin, vidal blanc, traminette and Norton. “Merlot and chardonnay are just a couple that everyone has heard of.”

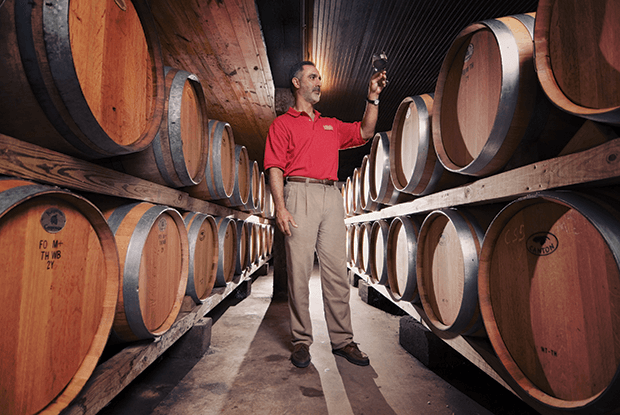

Finding the best vines for Maryland is a major part of Fiola’s research. Since it takes three or four years to produce a major crop, and seven or eight to develop a more mature taste, growers depend on Fiola—who makes about 100 to 150 batches of wine per year—to show them the best potential grapes for their region.

“It doesn’t matter how well they grow if they don’t make great wine,” Layton says.

Fiola, who plants vines at four research centers throughout the state, has won at least a half-dozen awards from the National American Wine Society Amateur Wine Competition each year over the last decade, including a double gold for a Cabernet Franc, three silvers and five bronzes in 2014 alone.

In addition to seeing which varieties from Maryland’s European cousins can grow well here, he’s also looked farther afield. He was one of the first to bring new Eastern European varieties to the United States—and the only one to see their potential and continue to grow them for years.

“They make the most beautiful, aromatic wine,” says Atticks. “They’ve never been in such a warm place, and they fruit prolifically.”

Fiola’s willingness to try the unusual (and the unpronounceable) has paid off: Big Cork Vineyards in Washington County became the first commercial grower to make wines from the Eastern European varieties. “Russian Kiss,” which won double gold in an international wine competition in 2014, is “stunningly beautiful,” Atticks says.

Fiola has expanded into other fruits as well. One colleague is studying the health benefits of antioxidant-rich chokeberries, so Fiola made a couple jugs of chokeberry wine to test its potential. He’s also experimented with apple wine, hard ciders and ice wine, which can create a major source of income for Maryland fruit growers competing with cheap Chinese apple concentrate.

Pests and disease are another area where growers look to Fiola and his extension team. With a new pathologist and new entomologist on board, he’s better able to diagnose and treat problems, like stinkbugs. He has a whole wall of stinkbug-infused wines, each with a different proportion of stinkbug to grape (one per gallon and up) to determine just how many of the insects can get into a batch before they affect the taste.

Fiola has also created detailed maps of the state that account for factors such as elevation, soil, slope, land use and zoning so potential growers can understand their farms’ grape-growing suitability and which varieties are most likely to thrive there.

But perhaps the most important thing is getting all of this information out to those who need it.

“He’s not only really good at research but really good at explaining and walking through what are the positives and negatives of what we’re dealing with here on the East Coast,” says Roy Crow ’77, owner of Crow Farm and Vineyard on the Eastern Shore.

Romance and Reality

“Don’t do it.”

That’s the first thing Fiola tells anyone attending his annual New Grower Workshop.

It might seem like an unlikely, even harsh, message from a man who’s trying to expand the industry—especially one who’s so friendly he prefers a hug over a handshake. But growing grapes is hard work, and he wants to ensure everyone who comes to him knows that. The labor-intensive crop requires constant canopy management throughout the growing season and careful pruning throughout the winter.

“People are seduced by the romance of the industry,” he says. About half of the people who come to these meetings have zero experience in agriculture, but have a vision of a charming little winery on a hillside, full of guests sipping cabernet sauvignon.

The other half are established farmers looking to diversify, perhaps those who have taken tobacco buyout money, or who plant soybeans, corn and wheat like Layton, whose family has farmed for generations.

When Layton decided to join the family business with his wife, Jennifer ’96, and work with his father, Joe ’70, he thought, “How are we going to carry the farm for the next 20 to 30 years?”

He wanted a crop with a lot of university and state support, and in the mid-2000s, that was grapes.

Fiola offered hands-on assistance, visiting the farm before Layton started planting to help establish the best location and point out the challenges of high groundwater. (Layton incorporated a tile drainage system to ensure dry soil for the grapes, which lose cold tolerance and flavor with too much water.) These days, when Layton sees an unusual insect or potential signs of disease, like patchy brown leaves, he shoots an email to Fiola to get his take.

Fiola also helped bolster state support by connecting with former state Sen. Donald Munson to show him Maryland’s wine potential. Munson worked to get then-Gov. Robert Ehrlich to create a state commission to offer grants to new growers and help promote the industry. It put in motion a decade of reforms. Today, wineries can sell wine by the glass to visitors and set up stands and offer samples at farmers markets, and Marylanders can now order wine online and receive it through the mail.

That’s helped farmers like Layton, who sold 50,000 bottles last year, just eight years after he planted his first vines.

Giving Maryland a Chance

After all he’s accomplished, Fiola could kick back, enjoy the more than 3,000 bottles of wine he’s collected with his wife, Deborah ’81, M.S. ’85, and watch his children, Jaclyn ’15 and Greg ’18, graduate college and enter the working world.

But he’s not satisfied. Fourteen years, the time he’s worked in Maryland, is nothing in the wine world. The Europeans have had millenia to perfect the craft, and even relative newcomers such as Chile and California have been refining their wines for centuries.

He also knows that no matter how much research he does and how many acres of grapes he helps get planted, none of it matters if nobody drinks it. Just 2.4 percent of the wine sold in the state is created in Maryland (up from 0.6 percent in 2001), and he’s thrown himself into promotion to convert more drinkers.

Fiola organizes the Maryland Governor’s Cup and Wine Masters competitions each year, as well as contests in Pennsylvania and New Jersey; he’s helped create wine trails to encourage day trips; and he promotes the health benefits of wine through workshops and dinners for the public. Those efforts have brought national recognition: The Drink Local Wine organization picked Maryland in 2013 as just the fifth state for its annual conference, bringing 100 wine reviewers from across the country to taste and evaluate Maryland wines. Restaurants as far away as New York and London have added Maryland wine to their lists, though the market is still primarily local.

So next time you’re browsing for a bottle, Fiola says, look beyond your everyday red or white or rosé, and give Maryland wine a swirl.

“You name it, we can produce it,” he says. “You just have to try it.” TERP

Tags

Research