- August 30, 2024

- By Sala Levin ’10

In George Bellows’ famous 1909 painting, “Both Members of This Club,” two prizefighters—one white, one Black—are locked in an intense struggle. The Black boxer looks to be winning, his powerful back curving over his white opponent, whose face and arms drip blood.

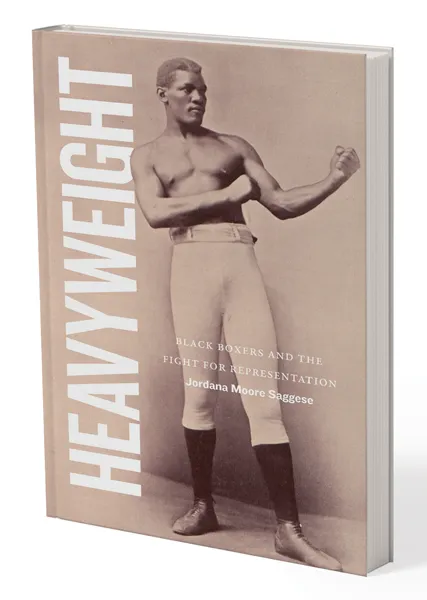

Though many art historians and critics have considered the artwork a daring representation of a victorious Black fighter, a new book out Friday by Jordana Moore Saggese argues that the painting—whose original title contained a racist slur—reflects widespread fears about Black people.

“Through the way Bellows paints this boxer, he becomes threatening, an aberration, a blob, this indiscriminate threat,” said Saggese, professor of modern and contemporary art as well as director of the David C. Driskell Center. “He has no face.”

In “Heavyweight: Black Boxers and the Fight for Representation,” she examines artistic depictions of Black boxers from the 19th through 21st centuries, revealing how their renderings reflected and reinforced stereotypes about Black men’s physicality, celebrity, power and place in the United States.

“The book is about imploring people to look beyond what they think of as iconic images of sport to what they might reveal about Black bodies in the public sphere,” Saggese said.

Boxing’s popularity in the 19th century rose alongside the proliferation of print media, making it a favorite topic of many artists. The sport, which predated football and basketball as a phenomenon, created the country’s earliest Black athletes.

Racist fears about Black boxers emerged in images. Jack Johnson, crowned the first Black world heavyweight boxing champion in 1908, was “reduced to monkey images, shown eating fried chicken and watermelon” to diminish his strength—not just as a boxer, but as a representative of Black men, Saggese said.

Other boxers were celebrated rather than vilified. When late 19th-century fighter Peter Jackson was pictured from behind, fully nude, on the cover of a national newspaper, he was compared with the classical marble statue Apollo Belvedere, sparking debates about which was the more beautiful man.

One of boxing’s most famous images, the 1965 photograph of Muhammad Ali standing over Sonny Liston during the world heavyweight title fight, also echoes neoclassical art, Saggese said. “You have this pyramidal composition of the figures, someone standing in the center of the frame very dramatically lit, elevated on stage. It looks very similar to 19th-century history paintings.”

For many Americans, she said, images of Black athletes remain the primary depiction of Black people in public life, making it essential to understand their impact. “Images of athletes are integral to our wider visual and cultural history of Black people in America,” she says.

Topics

Arts & Culture