- February 07, 2015

- By Karen Shih ’09

It was a Friday night when the police showed up at the Kerley house, carrying a cadaver.

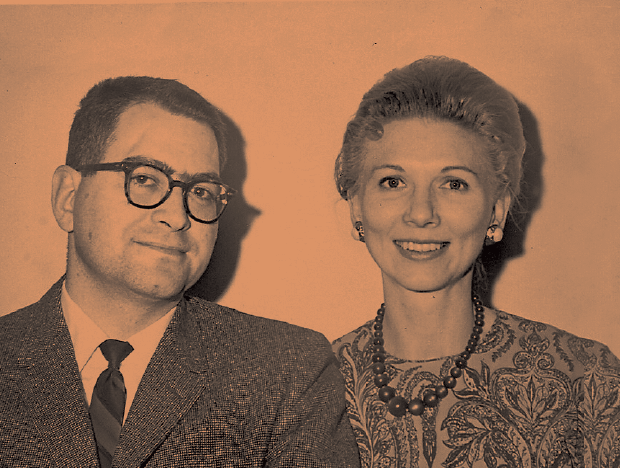

Ellis Kerley, the man they were looking for, wasn’t home. Instead, they found his wife, Mary, and young daughter, Amy.

“Mom said, ‘No, no, no, we’re not taking the remains here,’” recalls Amy Kerley Moorhouse ’88. But there was nowhere else to put them. Her father’s lab at the University of Maryland was closed for the weekend, and the body had been shipped all the way from Chicago. The only option left: Store it in the basement until he got home.

This situation would be unusual for anyone but Kerley (right), a trailblazing forensic anthropologist whose expertise in identifying bodies—sometimes from just a sliver of bone—made him a trusted authority internationally and gave him a role in some of the most important events of the 20th century.

His work took him from Japan to Brazil, where he famously identified the remains of Nazi fugitive Josef Mengele. From the Korean to the Vietnam wars, from the Iran hostage crisis to the Challenger space shuttle explosion, he provided clarity and closure to the survivors of those who died in violent or mysterious circumstances.

“He had such impressive knowledge,” says Douglas Ubelaker, a former Kerley student and curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s Department of Anthropology. Despite the media frenzy that followed many events, “he didn’t run out to the television cameras. He kept his focus on the science.”

Kerley’s high-profile cases earned legitimacy for a fledgling field that he organized nationally. At Maryland, where he spent nearly two decades, he created and led the Department of Anthropology, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year.

Now, an anonymous donor has established the Dr. Ellis R. Kerley Chair in Anthropology, spurring a new look at this remarkable man’s life.

Before "Bones"

Kerley was born in Covington, Ky., in 1924, the only child of two journalists. At 17, he enlisted and served as an Army rifleman in Europe during World War II.

He enrolled at the University of Kentucky (UK) upon his return, intending to follow in his parents’ footsteps. But after taking just one anthropology class, he was hooked. He graduated in 1950 with a bachelor’s degree in physical anthropology (as forensic anthropology was then known).

At that time, the field was new. The FBI had started turning to anthropologists at the National Museum of Natural History in the 1940s for help investigating skeletons. Students like Kerley, who started their studies shortly thereafter, had to look for specific classes at universities across the country and reach out to potential mentors at the Smithsonian.

Half a century later, shows like “Bones” and “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” have popularized the sleuthing done by forensic anthropologists. They analyze skeletal or badly decomposed human remains, determining the age, sex, ancestry and more, says Dana Austin ’86, president of the American Board of Forensic Anthropology (ABFA). They work with law enforcement and medical examiners to locate and recover bodies, determine how long a person has been dead and assess bone trauma to determine if any crime has been committed.

Despite what the surplus of TV procedurals suggest, the ABFA lists only around 70 board-certified forensic anthropologists. Local jurisdictions rarely have the budget for one on staff, so many work at universities and consult.

Nearly all in the field have a connection to Kerley, whose precise method of determining skeletal age is still used today.

A Forensic Sherlock Holmes

A fracture in the hip bone. A gap in the front teeth. Kerley and a team of scientists identified Mengele through those details, along with the technique for determining the age of skeletons he developed for his dissertation at the University of Michigan.

Bones store calcium until the body needs it. Once the bone matrix that stores calcium is absorbed, it leaves a small channel that is filled back in. As people age, there are more partially filled channels. Kerley found that by taking a cross-section of a long bone from the arm or leg and putting it under a microscope, he could count the number of partially and fully filled channels to determine the age of a person within two or three years. Previous techniques gave only a 10- to 15-year range.

Kerley, a meticulous researcher, used his method throughout decades of identifying the war dead and consulting for local law enforcement, as well as when the U.S. government called him for high-profile cases.

In 1976, he was part of a House investigation into President John F. Kennedy’s assassination; in 1978, he worked to identify the repatriated remains of the Jonestown, Guyana mass suicide victims; and in 1986, NASA called him in to examine remains of the astronauts in the Challenger space shuttle explosion.

“My dad felt the pressure,” says Moorhouse. “He didn’t like politics, he didn’t play games. That’s why he liked science so much, because science is the truth.”

He was called to Brazil in 1985 to ID the remains of the infamous doctor Mengele, who experimented on thousands at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Mengele had fled to South America after World War II, evading capture through fake names and frequent moves until his death by drowning in 1979. Many worldwide still believed the Nazi was alive—and his victims demanded justice. To provide absolute proof of his death, the scientists painstakingly reconstructed his skull and analyzed every bone, finding a hip fracture that matched his motorcycle injury at Auschwitz and a front tooth gap that matched a 1938 military photograph. Kerley also determined that he had died in his late 60s, fitting local descriptions of the fugitive.

“I feel quite confident this is indeed Mengele,” Kerley said in The New York Times, which dubbed him a “forensic Sherlock Holmes.”

“The Most Popular Anthropology Instructor”

He tackled all his biggest cases while at UMD—but few outside the department knew about his extracurricular activities.

“It’s rare to find someone like Ellis Kerley who knew so much but was so soft-spoken about it,” says Ubelaker.

Kerley came to Maryland in 1971 after brief stints at UK and University of Kansas, where he taught Ubelaker. When he arrived, anthropology was still a subset of the sociology department. By 1974, he’d successfully established the new anthropology department, which he chaired for the next four years.

Though Kerley was an effective administrator, his first love was teaching.

“He was arguably the most popular anthropology instructor we ever had,” says Professor Bill Stuart. Kerley’s classes filled Skinner Hall’s auditorium, then one of the university’s biggest classrooms.

An amateur photographer, Kerley created all his own slides and illustrated his lectures with thousands of examples of skeletons he’d examined.

Austin says those slides were “one of the best things about his classes.” Another was his sense of humor. “He appeared to be very serious, but then he would just come out with these really funny jokes, though they were very dry.”

Stuart remembers him as a great punster who created a sense of community for the small department, inviting everyone to his home nearby for holiday parties and more.

That proximity meant Kerley could easily take work back and forth, creating an unusual environment where his wife and three daughters learned plenty about his work too.

“We didn’t realize that not everyone’s father talked about bones and fingernails and time of death at the dinner table,” says Moorhouse.

“We didn’t realize that not everyone’s father talked about bones and fingernails and time of death at the dinner table,” says Moorhouse.

At the same time, their house was more alive than most. Kerley and his wife took in many strays, from the usual cats and dogs to horses and ducks—even monkeys, which he studied as part of his research on aging. Suzy, a chimpanzee, ate at the dinner table and walked around the yard hand-in-hand with Kerley.

His popularity with students, it seemed, extended to primates. “She liked my dad more than anyone else,” says Moorhouse.

A Lasting Impact

Kerley’s national recognition elevated the field. To secure the future for new generations of forensic anthropologists, he knew organization and education were crucial.

“The men who started this field really had a huge responsibility in setting the tone,” says anthropology lecturer Marilyn London. “Even if we pick up a single bone, we talk about it like an individual. We say, ‘This woman, this child.’”

Kerley helped establish the Physical Anthropology section of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences in 1972 and became the first forensic anthropologist to serve as the academy’s president. Determined to build and maintain the credibility of the science in the legal community, in 1977–78, he helped form the ABFA, which certifies forensic anthropologists across the country.

At Maryland, the department Kerley created has blossomed. Since he retired from UMD in 1987, it has added graduate programs and its faculty has grown to about 40, including affiliate professors.

Now the department has its first endowed professorship. Kerley, who died in 1998, left a deep impact on the donor, says department Chair Paul Shackel.

Though the recognition isn’t something the ever-modest Kerley would have asked for, he would have been happy to see his legacy live on, say his daughters.

“He wanted to grow the science of forensic anthropology,” says Laurelann Bundens. “It solves a lot of the mysteries that people want to have solved.” TERP