- September 18, 2023

- By Sala Levin ’10

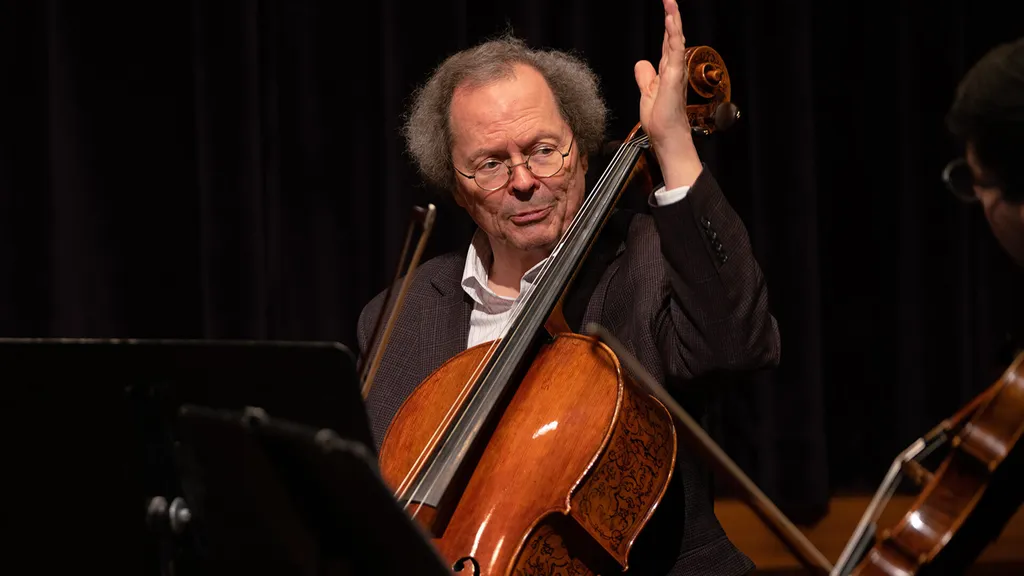

For many musicians, the chance to play a Stradivarius would be the highlight of a lifetime. For Kenneth Slowik, it’s just another day at the office.

The University of Maryland School of Music lecturer is also the curator of the musical instrument collection at the National Museum of American History, overseeing the conservation and restoration of thousands of historically significant instruments. In addition, he’s artistic director of the Smithsonian Chamber Music Society, a position in which he performs on these magnificent stringed instruments and the museum’s violas da gamba, harpsichords and fortepianos.

“People often say, ‘How can you take something in your hands that you know is priceless and not be very nervous about it?’” Slowik said. “I say, ‘Well, one way you do that is not to think about it: you just treat it with the same respect you give any fine instrument.”

His interest in classical music began at an early age, stoked by his father’s love of the genre and the gift of an upright piano from his grandparents. He started taking cello lessons in elementary school and eventually earned a doctorate in musical arts at Johns Hopkins University. (Love of classical music is a family trait: Slowik’s brother, Peter, is a professor of viola at Oberlin Conservatory of Music.)

Maryland Today talked with Slowik, who’s taught at UMD since 1978, about unusual instruments, how playing a centuries-old violin can change a musician and how Prince got into the Smithsonian.

How did you discover your love of niche instruments like the viola da gamba and the baryton?

My father was a stage director who occasionally directed for opera productions. He’d often be looking for snippets of music that he could put in as an accompaniment to plays he was directing. When I was about 7 or 8, he brought home a record of music from the 1730s or so played on period instruments; it came with extensive notes about not only the pieces but also the instruments. I was just taken away by what I thought were very beautiful sounds. When I was about 12, I finally had saved up enough money to buy a mail-order build-your-own harpsichord kit. It wasn’t a great instrument, but it did give me a chance to do something with my hands and to begin to explore the repertoire. That was my first niche instrument.

What does your job at the Smithsonian entail?

One of the things I do is host musicians who’ve made an appointment to come and play. After all, we’re a public institution, so you too, as an American citizen, own one microscopic part of a Stradivarius. Some people are immediately blown away by an instrument, and they don’t get very far beyond that feeling. With other people, you can hear them going deeper and deeper into the sound, and there are people who tell me 10 or 20 years after the fact that a couple hours of contact with that instrument has changed the way they approach everything they play.

So, can anyone make an appointment and play one of these instruments?

We have some ways of asking questions to see if this is really something that will make a difference in their musical lives. When people try to make appointments, I try to find out where they are on the spectrum of experience. In setting up their visit, I always ask them to bring their own instrument, which I look at very carefully. If it’s in great shape, I feel more comfortable about letting them play. If it has nicks, I’ll be watching them like a hawk!

How many instruments does the Smithsonian have in its collection?

Where I am, at the National Museum of American History, where the instruments are mostly from the Western traditions, we have about 5,000. In the National Museum of Natural History, there are over 300 instruments in the collection of Chinese cultural objects alone, and there are other similar “ethnic” collections around the other Smithsonian museums, bringing the total to several thousand more. A lot are stacked in crates in climate-controlled storage, and you need a forklift to access them. So they might not be looked at for some time, but then there’ll be some researcher who says, “Well, you have one of the few surviving instruments from this particular maker I’m studying.” You can think about the collection the way you’d think about a library: a book could sit on the shelf for a number of years before anyone comes and looks at it, but it could contain remarkable information.

What are some of the most unusual instruments in the collection?

There’s an instrument called an ocarina—it’s usually made of clay and shaped like a football with finger holes. It’s like a recorder or a very simple flute, and it’s usually 3 to 6 inches in size. We have an amplified one made of papier-mâché that’s a little over 2 feet long, painted bright green, made by a jazz bass player who found it more convenient to lug to gigs than his bulky stand-up bass. Its exaggerated size and amplification meant it could “toot along” in the bass register, sounding uncannily like a plucked acoustical upright bass. We have a banjo made by an American soldier after World War I. He collected some German rifles and bullets and a big artillery shell made in Düsseldorf to pound Allied forces. He cut about four inches off the shell, and it became the back and sides of a banjo. The neck he made from the rifle barrel, and the tuning pegs he made from 3-inch-long bullets. We have a guitar called the Yellow Cloud, made for the musician Prince. It’s a bright yellow electric guitar in Prince’s signature shape. He had several of these made, and he’d send them back to the maker when he got tired of the color and have them spray a new color.

If the Smithsonian were burning down and you could only save one instrument, what would it be?

A 1701 cello by Antonio Stradivari that’s known as the Servais. Adrien-François Servais was a 19th-century Belgian cellist who owned it from about 1849 to the 1860s. It’s a very specially preserved instrument with lots of original features that haven’t been altered. But we pride ourselves both on our security, thanks to our ever-vigilant Office of Protection Services, and our fire suppression system!