- January 30, 2024

- By Karen Shih ’09

Most elementary schoolers never stretched out in a PET scan machine for kicks after school or used what they know about electrocardiograms to win a spelling bee.

But growing up with a dad who installed and repaired hospital equipment, Associate Professor of English Christina Walter developed a fascination with technologies for studying the human body at an early age.

She carried it into her path in academia, focusing on early 20th century literature in an age of transformational scientific discoveries, from penicillin to the rise of medical x-rays.

“Writers and artists are using these experiments and inventions as prompts to think about the implications of science,” said Walter.

Since joining UMD in 2008, she has explored the psychology and physiology of human vision and is now examining how popular conceptions of the gut microbiome—the most fundamental of bodily systems—have changed.

From her office in Tawes Hall, Walter explains why she has glass eyes on her windowsill, how she got a piece of Virginia Woolf’s house and the edible nature of one of her class projects.

Optical objects

During the two world wars, “many soldiers were coming back with various forms of disfigurement,” she said, leading to more widespread use of glass eyes. The two on her windowsill were featured on the cover of her 2014 book, “Optical Impersonality: Science, Images, and Literary Modernism.”

She’s collected various optical technologies from the 1800s and 1900s through her studies, including a blue eye bath, a kaleidoscope, opera glasses, thaumatropes (paper with images printed on both sides that can be spun to combine them) and anamorphic art (distorted images that need to be reflected on a mirrored cylinder to be seen clearly).

“Each toy is trying to help you see a different thing about how human vision works. In the later 19th century, you have this big shift in how people think about vision. It’s no longer ‘seeing is believing.’ These devices and lenses are designed to exploit how human vision works.”

A piece of Virginia Woolf’s property

With her focus on British literature, Walter frequently travels across the pond for research and conferences. One trip took her to Sussex, where she stopped by Monk’s House, a 16th-century cottage that was the home of famed author Virginia Woolf.

“After she died by suicide, her husband spread her ashes in the garden right in front of this wall,” said Walter, who wrote about Woolf and her work in her book. “They were working on the wall when I visited, and the gardener let me take that piece (of the wall).”

Jars of detritus

As Walter reads old papers or visits historical sites with literary connections, she collects crumbled scraps, twigs or even dried rosehip associated with writers like Mina Loy, H.D. and Woolf.

“There’s zero use value to these,” said Walter. “For me, it’s what we would call pure aura.” She keeps them in little blue jars, labeled in cursive with the author’s name or location.

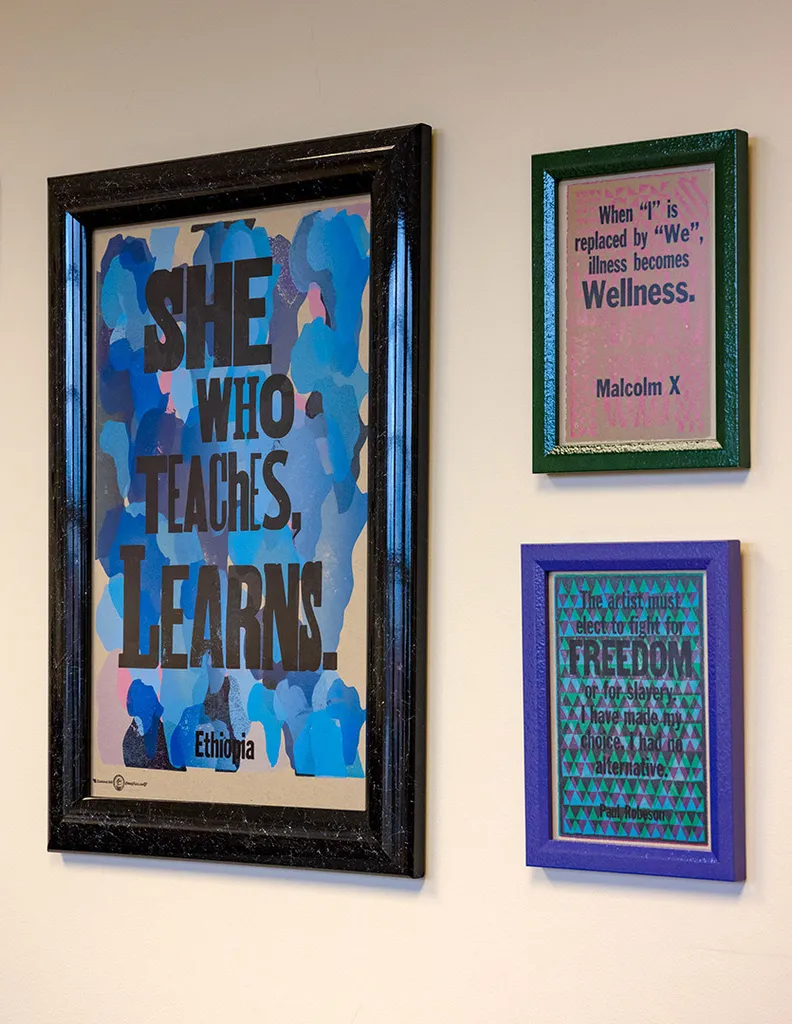

Wall prints

The prints were made by Amos Kennedy, an African American artist known for social and political commentary, who visited the BookLab makerspace next to Walter’s office just before the pandemic.

“It was a big visit for us in terms of thinking about BookLab as a space for engaging in social justice,” she said. Kennedy hosted workshops on his techniques, which inspired students to create their own political messages.

Owl pellet and edible booklets

The teeth (both real and 3D-printed) and owl pellet (which students dissect) are part of her exploration of the culture of food and digestion, including the gut microbiome, for her next book. “We navigate the world through metaphors, and for a long time, because bacteria was thought to be bad, conversations around bacteria in the body were about war and invasion,” she said. “There’s a narrative shift now to collaboration, to how we’re only 10% human, and that embodied within us and enabling us to live are microbes” that make up 90% of the body.

She also teaches multiple classes on food, culture and literature. In one course, called “Food Words, Stories, Being, and the Gut,” students create booklets made of edible, culinary-grade paper and ink (the type used to put photos on cakes), telling the story of a personally significant food and sharing the recipe.

This is part of an occasional series offering a look inside some of the most interesting faculty and staff offices around campus. Think you have a cool workspace—or know someone’s that you’d like to recommend? Email kshih@umd.edu.

Topics

Campus & Community