- February 11, 2026

- By Karen Shih ’09

You’ve probably walked past the statue of a striking young Frederick Douglass in mid-speech overlooking Hornbake Plaza dozens of times. But if you take just a few more steps into the library behind it, you can read elegant script penned by the orator, abolitionist and statesman himself—and get a firsthand look at how the famed Marylander spread the word about the cruelties of enslavement and advocated for freedom in the 19th century.

The University of Maryland Libraries’ Special Collections and University Archives, housed primarily at Hornbake Library, features a treasure trove of materials by advocates of emancipation, including numerous works by Douglass.

Through primary sources at UMD, people can trace Douglass’ “life story, and his movements across the country as he continued to speak at organizations and spread the message of abolition and anti-slavery” said Jeannette Schollaert, outreach and engagement librarian. “It's really interesting to see how this one man helped to power a movement … and how he contributed to national and international history.”

These materials are accessible to UMD researchers and students, such as those who visit Hornbake for instruction sessions like those in the College Park Scholars’ Justice and Legal Thought program, as well as external community members interested in genealogy. Anyone can make an account with Special Collections and request a time to view the items, which are usually stored in climate-controlled areas.

“It might seem like Special Collections appointments are only open to folks with a set research question or that you need to be writing a dissertation to justify your appointment, but no,” said Schollaert. “If you are curious and want to hold these materials in your hands, get in touch. We’re happy to help you.”

In honor of Douglass’ birthday, celebrated on Feb. 14, here are five items he wrote that you can see at UMD.

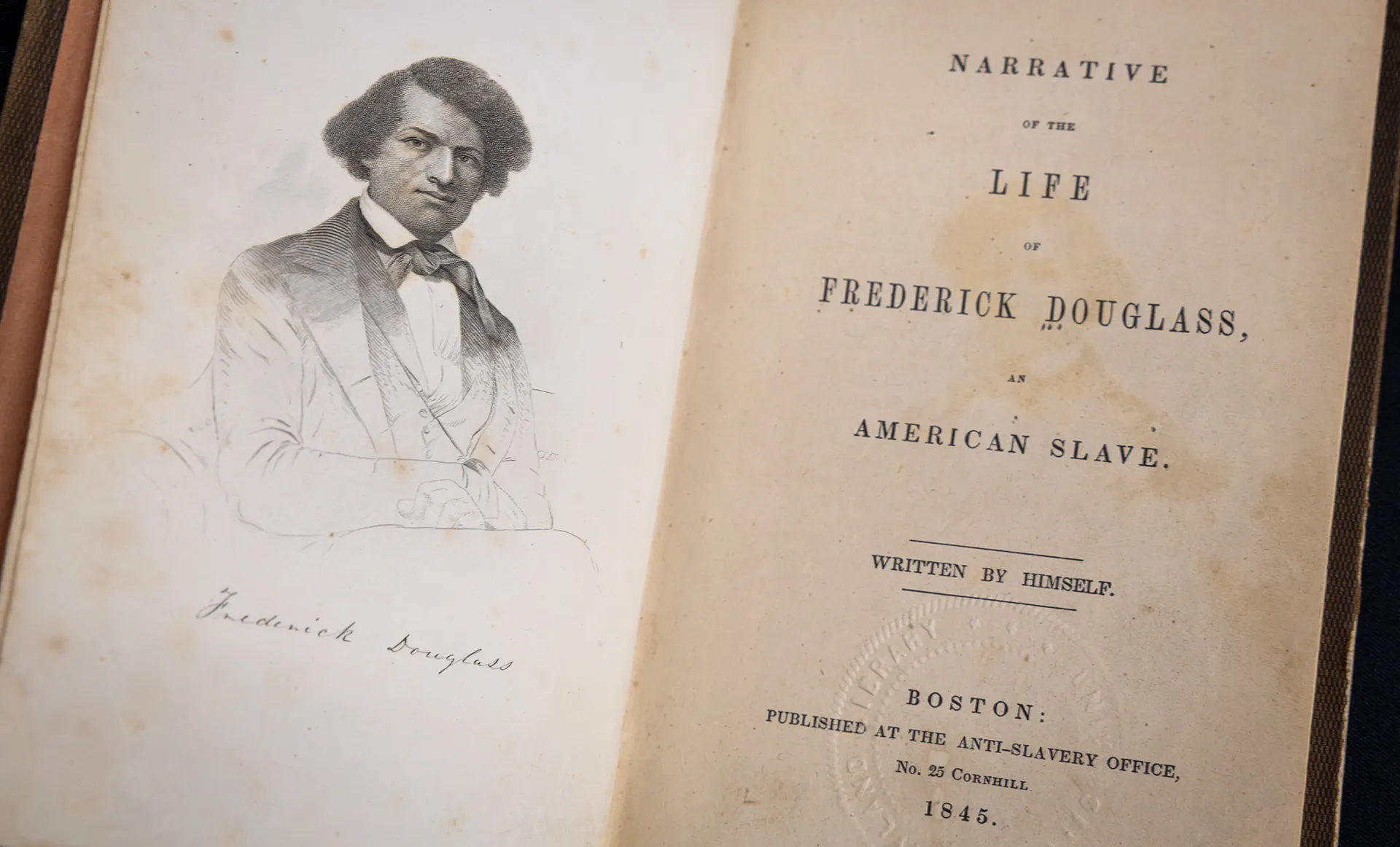

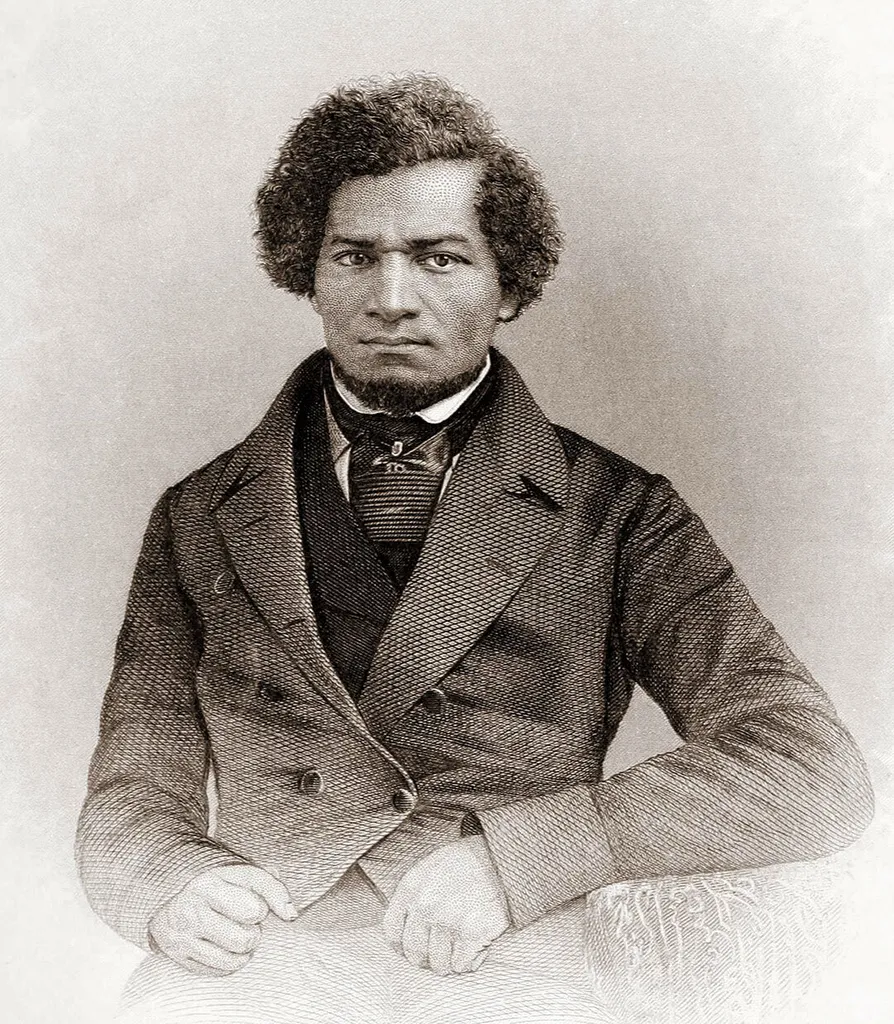

“Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass”: This first edition of his initial autobiography from 1845, detailing his early life as an enslaved person on the Eastern Shore and Baltimore and eventual escape in 1838, became one of the most influential pieces of the abolition movement. “Whenever I bring students in to look at rare books, they think they're copies,” said Amber Kohl, curator of literature and rare books collections. But “this is what, if you lived in Frederick Douglass’ time, you would have purchased if you went to the bookstore.”

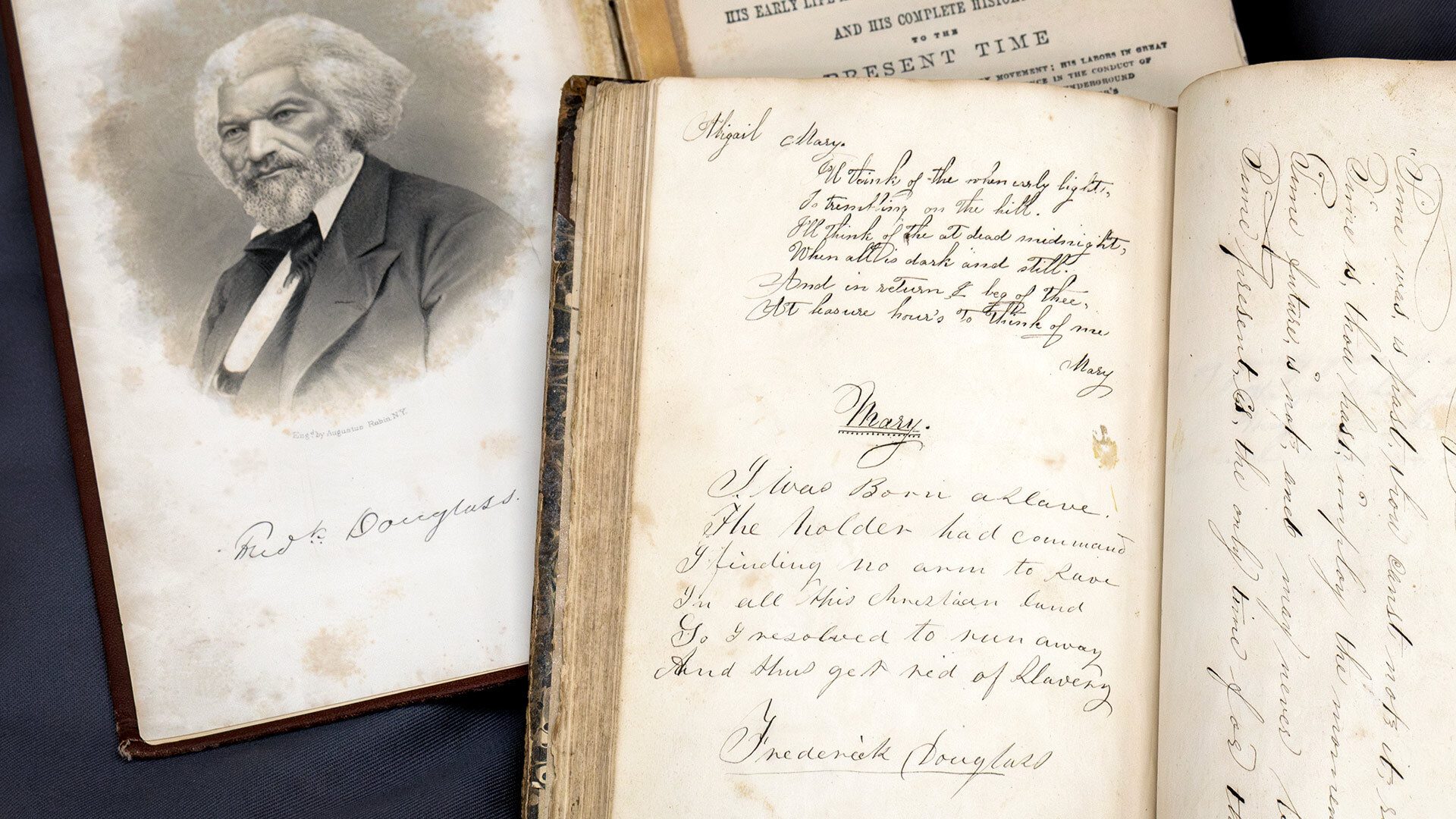

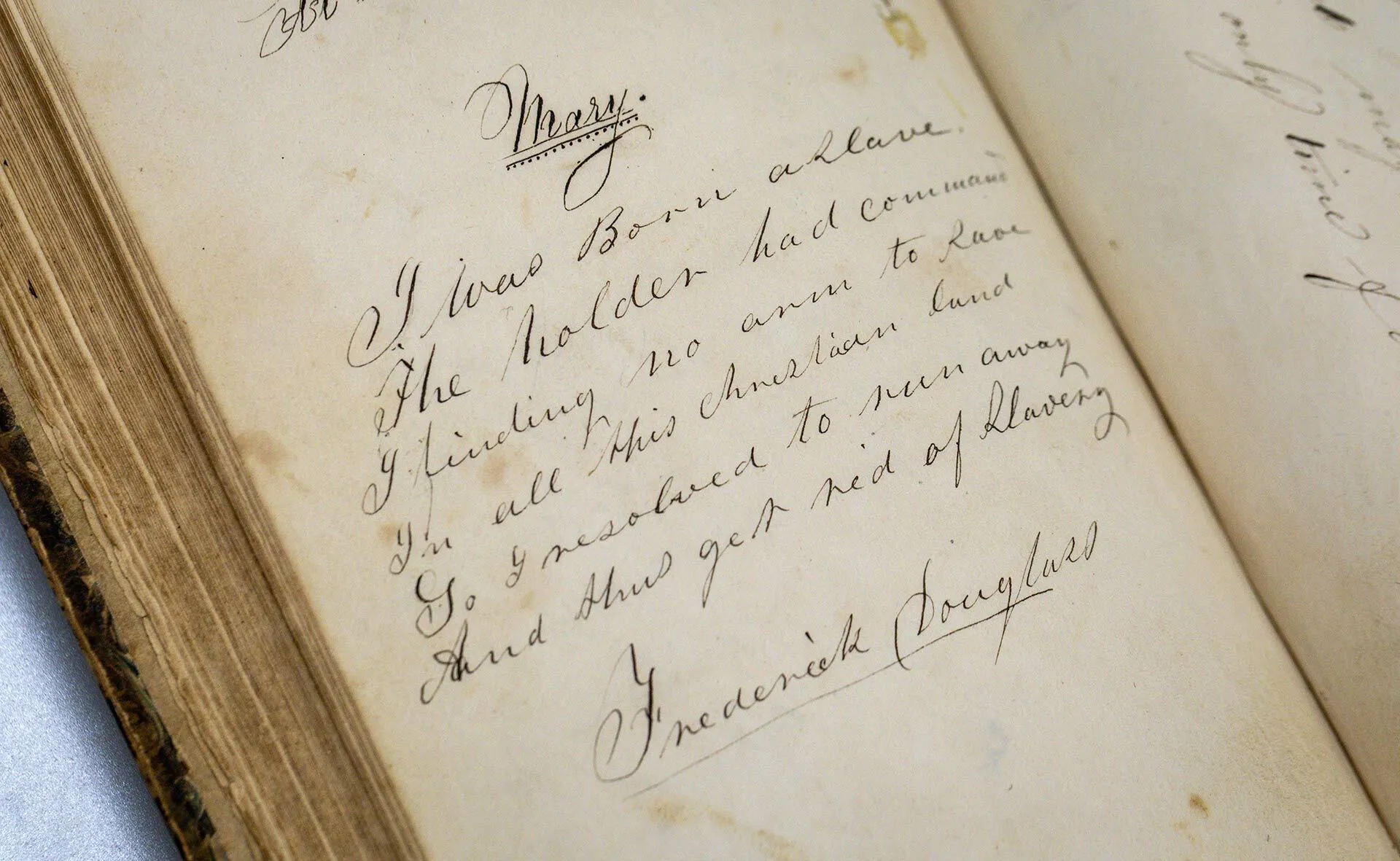

Abigail Fisher’s memory book: This notebook of a Maryland resident, dated to between 1825 and 1847, features a poem handwritten by Douglass as well as his autograph. The poem reads: “I was born a slave / The holder had command / I finding no arm to save / In all this christian land / So I resolved to run away / And thus get rid of slavery.” He wrote versions of this poem in other guestbooks as he championed liberty for African Americans across the country. Knowing that he wrote those words by hand, “you get chills and a sense of wonder,” said Schollaert.

“My Bondage and My Freedom”: The 1855 autobiography, another first edition, expands on his journey to freedom and explores his advocacy for not only abolition, but also women’s rights, and his work as a speaker and newspaper publisher. In addition to the Douglass biographies, Special Collections also has early editions of “12 Years a Slave,” written in 1853 by Solomon Northrup, a free man kidnapped and sold to the South, and “Slavery in the United States,” by Charles Ball in 1837, a fugitive enslaved man who was born in Calvert County, Md. “With these narratives, there's always the question who's writing it? Whose perspective is this? Is this a white person writing on behalf of someone else? Has it been significantly edited? When the narrative is a first hand account of a genuine lived experience, it lends more power and authenticity to the historical resource,” said Kohl.

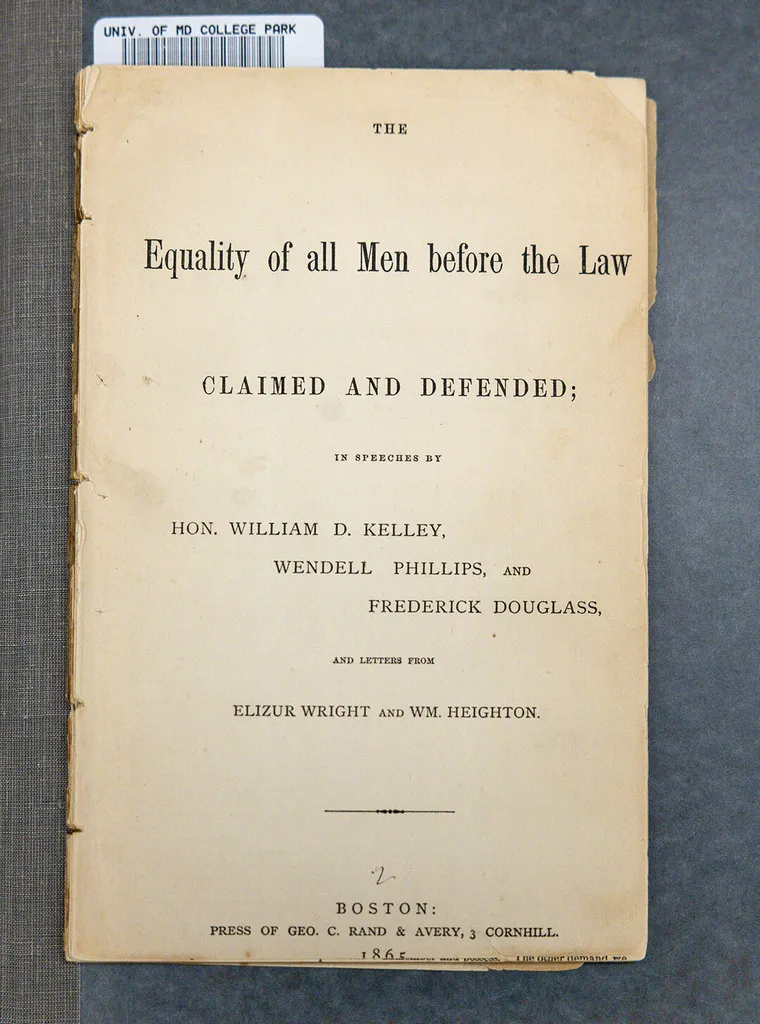

“Equality of all Men before the Law”: Pamphlets were inexpensive to print and distribute in the mid-19th century, said Kohl. “The purpose is to get the word out about abolition, spread awareness and education about, and rouse public support for the cause.” This one published in Boston in 1865 features speeches by William D. Kelley, Wendell Phillips and Douglass, including his famous quote, “What I ask for the negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice.”

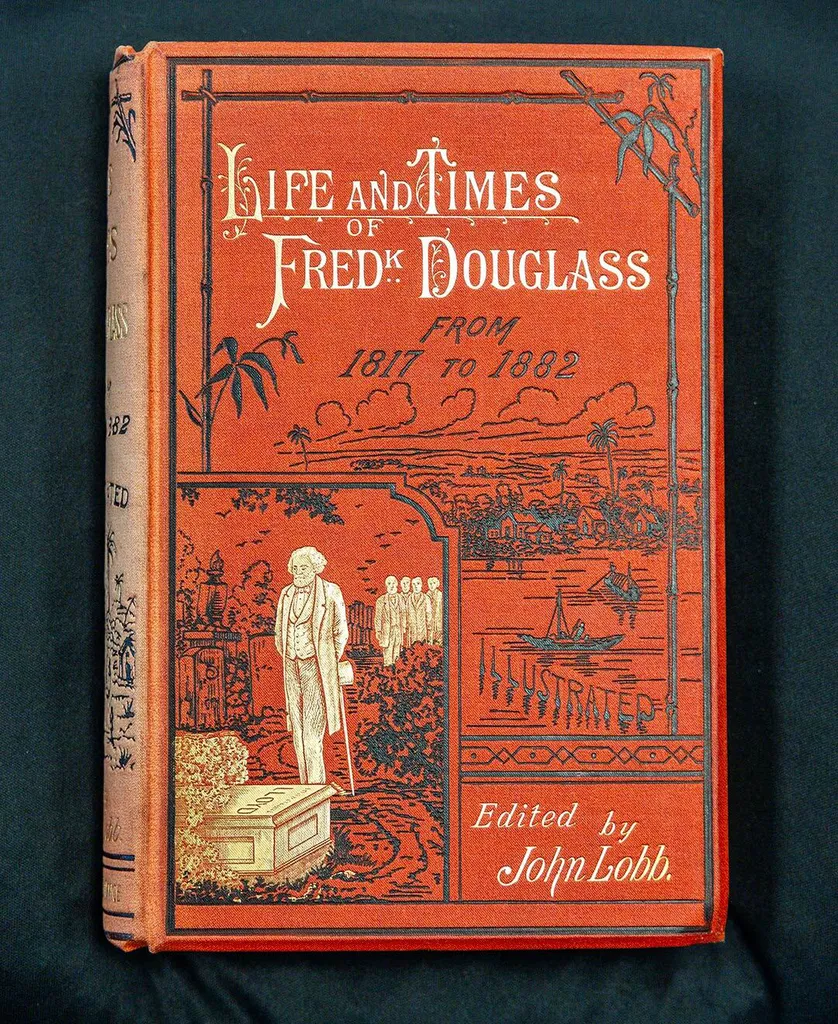

“Life and Times of Frederick Douglass”: Written after the Civil War in 1881, the book reveals new details about his life as an enslaved person that would have previously put him in danger, as well as chronicles his encounters with Presidents Abraham Lincoln and James Garfield. A later edition with a striking embossed red cover, depicting Douglass as an older man, is currently on display on the first floor of Hornbake Library as part of its “Unboxing Innovation” exhibition.

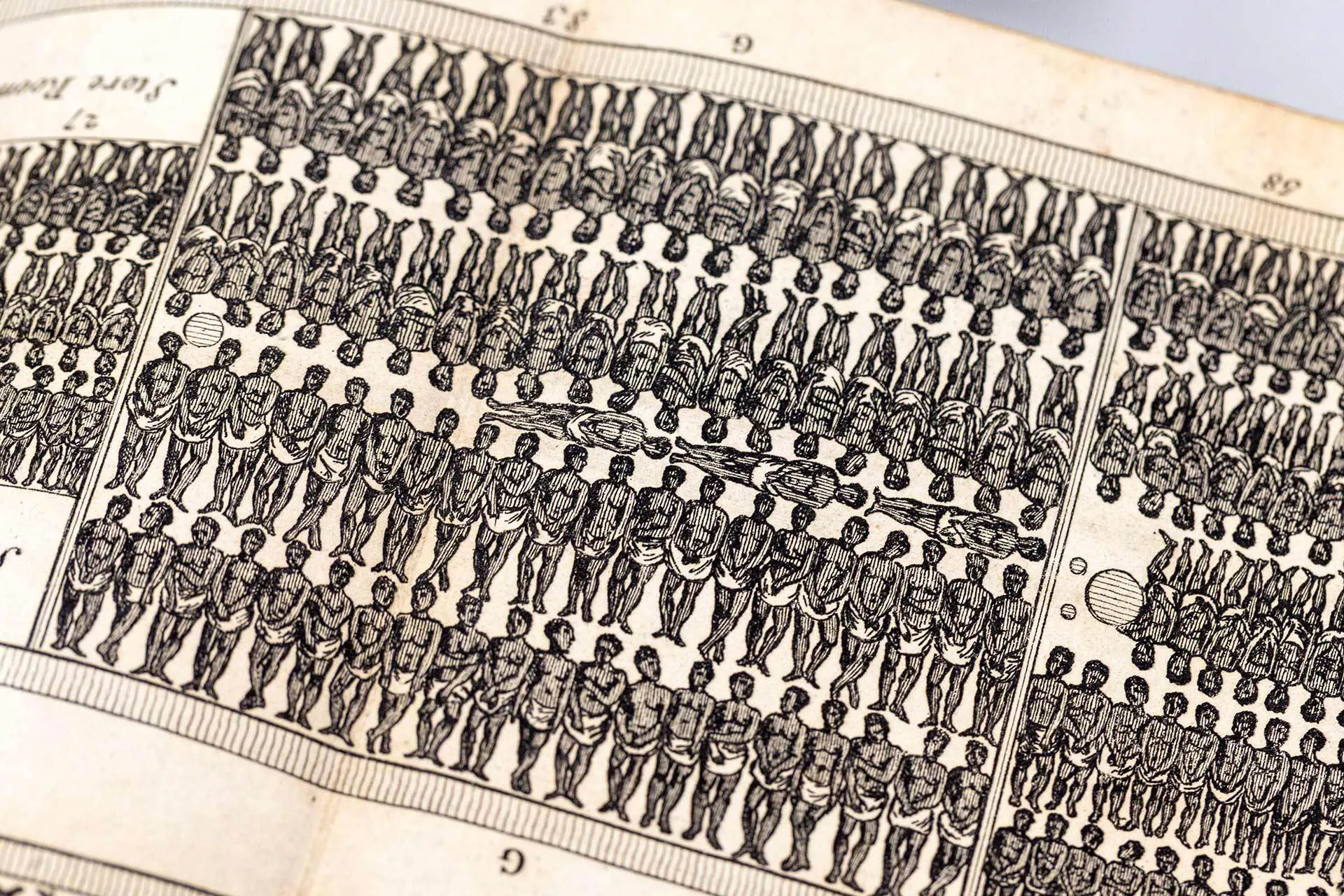

Bonus: “The History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament” by Thomas Clarkson: Though not a work by Douglass, this 1808 book contains a fold-out diagram depicting the inhumane transportation of enslaved people arriving in ships from Africa. “It becomes a lightning rod for the abolitionist movement. The imagery is so striking, it becomes a symbol for people rallying against slavery,” said Kohl, noting that it was reprinted in broadside posters and pamphlets to further the cause. “When you think about images in history that provoke real change, the impact of this illustration was massive.”

Topics

Campus & CommunityTags

HistoryUnits

University Libraries