- November 15, 2022

- By Maggie Haslam

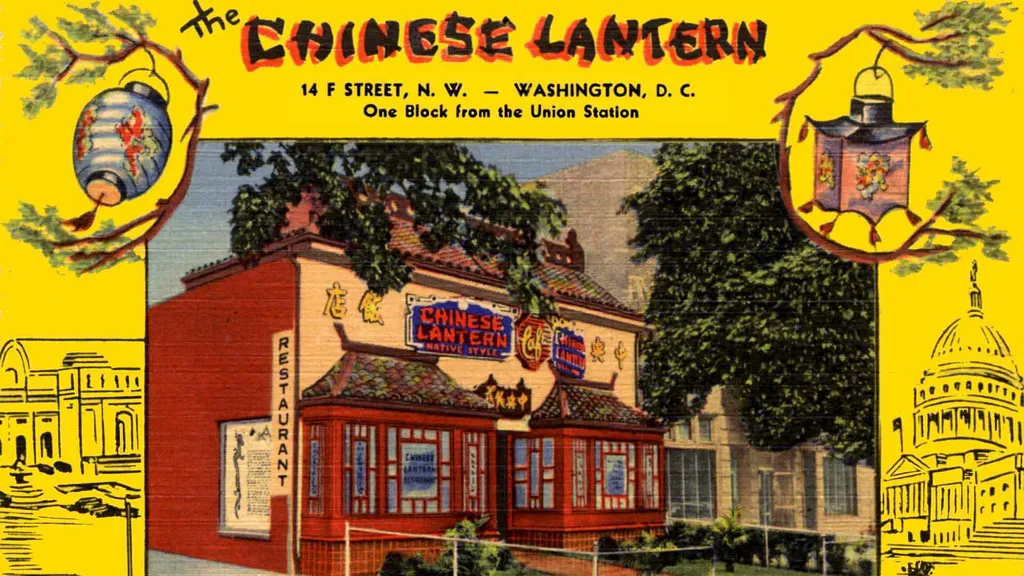

Where tourists now stroll by Vermeers, da Vincis and Rothkos in the National Gallery of Art was once a bustling and vibrant immigrant community of teashops and laundries, groceries and tailors.

Washington, D.C.’s first Chinatown was razed as part of the New Deal construction boom to make way for what’s now a famed corner of the nation’s capital, but for the past 18 months, a team of researchers has worked to ensure that other physical remnants of local Asian American culture are remembered, preserved and celebrated.

An ongoing project led in part by Assistant Professor of Historic Preservation Michelle Magalong will produce Washington, D.C.’s first Chinese and Korean “historic context statement,” which will trace the cultural impact and historical presence of Chinese and Korean immigrants in Washington, D.C.

Developed under the auspices of the nonprofit 1882 Foundation and in collaboration with the University of Maryland, the D.C. Preservation League, the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and the National Park Service, the document will guide city officials in planning, preservation and development efforts. It will also serve as a historic reference to elevate an Asian American immigrant experience largely left out of the D.C. narrative.

“It's a protection measure, but it also tells a story that people might not understand or know,” says Magalong. “People walk down these streets every day not knowing what happened there.”

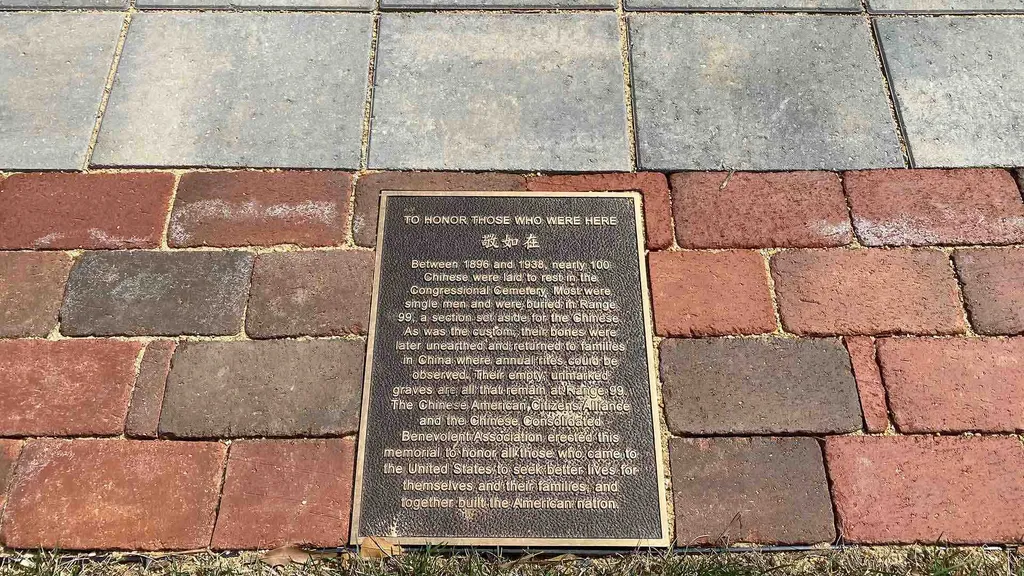

The research builds on extensive heritage work by community groups, academia and organizations like the 1882 Foundation—which seeks to broaden historical understanding of anti-Asian laws and sentiments—chronicled in articles, dissertations, exhibitions and public programs. Project researchers also collected census data, newspaper clippings and hundreds of oral histories and photographs to fill knowledge gaps and connect the dots across communities and timelines. The result is a synthesis of places, events and people who played a part in shaping the city’s fabric, culture, geography and politics.

“You see a place differently when you learn about its history,” said Sojin Kim, a curator for the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage who is co-leading the project. “You begin to get a picture for how people moved, where they were or were not allowed to be. I think one of the work’s biggest values is that it’s connecting things that might not have been connected before.”

U.S. military service, family associations, Chinese laundries and martial arts are just a few themes that have emerged, helping researchers choose actual buildings and places for evaluation and possible nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. The team has earmarked two dozen sites so far.

“I always thought of preservation as being a very physical discipline, but this project gave me the mindset to incorporate people’s history,” said graduate student Emma Lucier-Keller, who pieced together early D.C. history with the help of census and genealogy websites. “This is about making a narrative that is relevant to all people.”

What hasn’t escaped anyone involved in the project is its urgency; the commercial development that has long displaced immigrant and marginalized communities and shuttered their longtime landmarks throughout the District continues today, said Magalong. Archival documents with the D.C. government offer clues to places that disappeared around modern-day Chinatown—much of which was scrapped to construct the Gallery Place Metro Station in the 1970s, followed by a sports arena and a convention center (now demolished) in the 1980s and ’90s—and now known to many of local stakeholders as “China block.”

Magalong, who has conducted dozens of family interviews, has seen the surprise of younger generations as they hear stories from their immigrant families of places long gone.

“Often, immigrants don’t recognize the greater importance of their experience or think about how they are connected to the bigger story,” she said.

While the scope of this study encompasses mainly Chinese and Korean Americans, the team is including other cultural heritages as well, such as Japanese and Filipino. They hope that the study, which project leads expect to be complete next spring, establishes a framework to capture the histories and experiences of cultures that have yet to be fully acknowledged in the American story.

“I have a deeper appreciation for that longstanding history and the fact that their struggle is what made us able to come to this country,” says Karen Yee M.H.P./M.C.P. ’22, a first-generation Chinese American who worked on the project for over a year. “I walk through Chinatown every day now on my way to work; I find that I walk slower now.”