- May 12, 2025

- By Aleena Haroon M.P.P. ’25

A University of Maryland faculty-student team has cracked a mathematical quandary that stumped scientists for more than 35 years, but it’s more than just a clever solution to a puzzle: The discovery could boost the power and energy efficiency of the chips used to run computers and power AI systems.

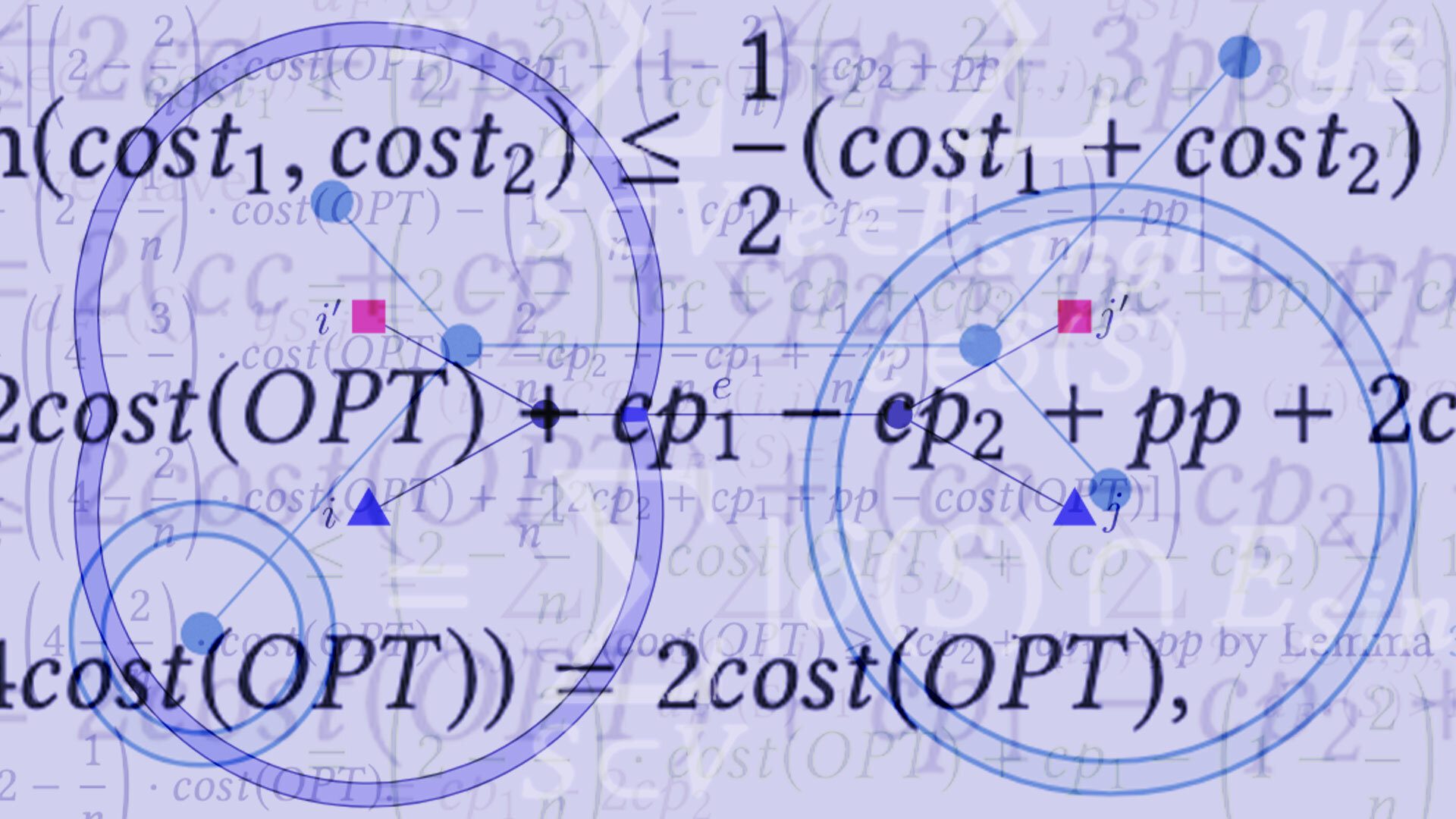

Led by Mohammad T. Hajiaghayi, the Jack and Rita G. Minker Professor of Computer Science, the group recently published a 126-page paper advancing the solution to the Steiner Forest problem—a network optimization challenge seeking a minimum-cost subgraph that connects a set of terminal pairs in each graph—with a recent Journal of the ACM paper on a similar subject serving as a first step toward this result.

So what does that mean? Imagine you want to set up several lights in your living room, but to do so, you need to figure out the best way to connect the lights using electric wire, possibly through some shared junctions. What if there was a mathematical formula to determine the minimum amount of wire you needed to buy, so you could avoid a mess of cables while also saving cash?

This is where the Steiner Forest problem comes in. In mathematics and computer science, the use of network optimization algorithms can often determine the shortest way to connect a set of points in a network. By applying a Steiner Forest solution, you can plan your lighting setup to be cost-effective and clean.

But the Steiner Forest problem has many more applications than helping with home décor. Modern computer and AI chips contain millions of tiny transistors that need to be connected. Hajiaghayi and his team’s new Steiner Forest algorithm can help tech giants like Nvidia and Google design the shortest wiring paths between these components, slashing costs and energy usage. In the era of artificial intelligence’s vast and growing hunger for computing power, this can allow these and other companies to create faster models that consume less.

Yet despite its significance, the Steiner Forest problem has resisted attempts at more efficiency for years. In 1989, an algorithm was proposed that guaranteed the solution would cost no more than twice the optimal network—named the “2-approximation.”

Since then, scientists have produced solutions that are 60 or 90 times higher than the optimal cost. “But these results were still published because the problem is considered so central—and it was thought that even such solutions could help drive future improvements,” said Hajiaghayi, who has appointments in the University of Maryland Institute for Advanced Computer Studies, the Artificial Intelligence Interdisciplinary Institute at Maryland and the University of Maryland Center for Machine Learning.

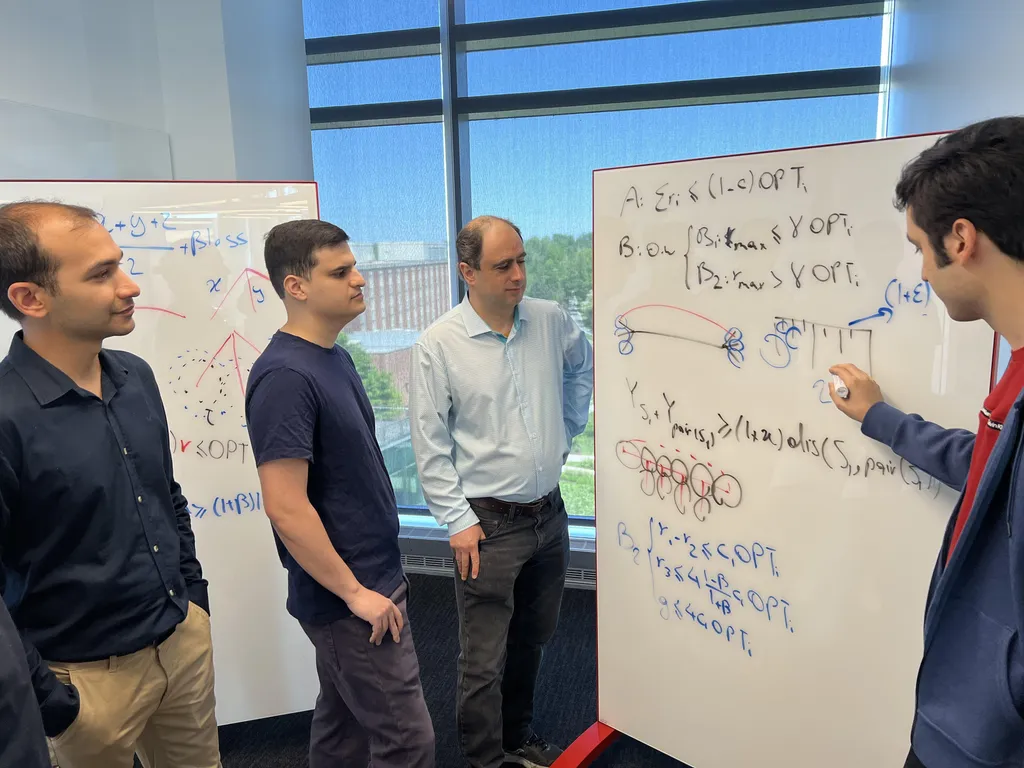

Assisting Hajiaghayi on the project were Ali Ahmadi, Iman Gholami, Mohammad Mahdavi and Peyman Jabbarzade, all doctoral students in the university’s computer science program.

The four students are International Olympiad in Informatics medalists, an honor that recognizes secondary school students representing countries worldwide in a programming competition.

Hajiaghayi and his graduate students worked on the Steiner Forest problem for three years. The team faced numerous challenges, including dead ends and “bad examples” that stalled their progress.

They wrote their final proof over four exhausting months. “Writing it was horrible,” said Hajiaghayi. “Every detail had to be triple checked.”

The results were worth it, they said. For Jabbarzade, collaboration was key: “The breakthrough came from working together with my peers—we couldn’t have done it alone.”

It was a risky undertaking, with no guarantee of their efforts coming to fruition.

“These students gave up lucrative careers to come work on this problem with me,” said Hajiaghayi. “But now their efforts have paid off.”