- July 29, 2014

- By David Kohn

In 1985, 12-year-old Scott Weaver did a self-experiment involving wind velocity, riding his skateboard in Hurricane Gloria. “I got blown down the street,” he says.

Whenever a thunderstorm rolled in, he sat in the doorway of his garage in Edison, N.J., watching as dark clouds advanced and rain pelted down. He had what he calls “weather envy,” a fervent wish to live in the Midwest, where the flat terrain is ideal for viewing weather patterns. “You can see these storms coming from 30 miles away,” he says dreamily.

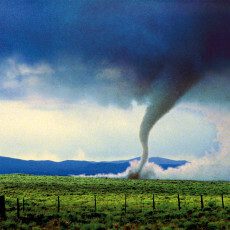

Weaver M.S. ’03, Ph.D. ’07 now spends his days studying the weather of this same region: He is a meteorologist for the Climate Prediction Center at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration offices in College Park. He focuses much of his work on tornadoes, the most dramatic of Midwestern weather. Every year, an average of more than 1,200 tornadoes hit the U.S. Most do relatively little harm, but some can be extremely destructive: The 2011 storm that hit Joplin, Mo., killed 158 people and caused nearly $3 billion in damage.

Weaver has been working on seasonal forecasts for tornadoes, just as scientists do for hurricanes. Because tornadoes last for only a few minutes and are comparatively tiny—a mile or so wide, hundreds of times smaller than a hurricane—they are extremely difficult to predict. “We can’t get more precise than that right now,” he says. “I don’t know if we’ll ever be able to do that.” Instead Weaver is trying to better understand the larger meteorological forces that determine broad tornado risk over several months and hundreds of thousands of miles.

One key, he thinks, is a ribbon of air a mile above the Midwest known as the Great Plains Low Level Jet, which in the summer carries warm air from the Gulf of Mexico all the way to North Dakota. This massive stream slams into another air column, the Upper Level Jet, which carries air across the country from west to east. The collision creates wind shear, a swirling airborne cross current that in volatile, stormy conditions can create funnel clouds and tornadoes. (Funnel clouds are tornadoes that don’t touch the ground.) The moist, warm air destabilizes the atmosphere, creating volatile conditions that can lead to swirling destruction.

Weaver’s work, which involves mathematical modeling using meteorological data over several decades, indicates that global warming is increasing the force and power of the Great Plains Lower Level Jet. This in turn appears to ramp up the level of wind shear in the Midwest, increasing the overall risk for tornadoes.

Weaver’s work, which involves mathematical modeling using meteorological data over several decades, indicates that global warming is increasing the force and power of the Great Plains Lower Level Jet. This in turn appears to ramp up the level of wind shear in the Midwest, increasing the overall risk for tornadoes.

His research is receiving recognition: In April, he was awarded a Presidential Early Career Award in a White House ceremony. “His work on lower-level jets is really promising,” says Utah State University climate scientist Simon Wang, who also studies the interaction of short-term weather and long-term climate change. “We are just realizing how little we know about tornadoes and other extreme events.”

With his sturdy physique and buzz cut, Weaver looks less like an egghead scientist than a suburban family guy, which he also is: He lives in Boyds, Md., with his wife, a clinical psychologist, and their 3-year-old daughter. He describes himself as a “blue-collar scientist” who chips away at complex meteorological questions. (He has recently taken on another task, working with graduate students in the UMD Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science. Next year he will begin teaching there as an adjunct professor.)

In addition to the tornado question, Weaver is also chipping away at another Midwestern meteorological mystery. Over the past 60 years, average summer temperatures throughout the U.S. have risen by about 1 degree Fahrenheit, a significant jump in climatic terms—except in the Midwest, where they have stayed the same or even dropped a bit. This seeming exception to global warming, known as the Central U.S. Warming Hole, has intrigued scientists for many years. Many explanations have been proposed, including the idea that irrigation from Midwestern farms has caused the cooling.

Weaver has developed a different theory, one that also involves moisture. His models show that as the increasingly powerful Great Plains Jet brings water-laden air from the Gulf, the Midwest’s climate has cooled a bit. He emphasizes that his models don’t explain why it’s cold one day or warm the next. But he believes that over longer time periods, science can explain how the climate system does what it does.

“It’s like counting cards,” he says. “You won’t be right every time, but you definitely improve your chances. It’s all probability.”