- August 16, 2016

- By Liam Farrell

Frank and Ethel Turner paid $25 a week for 10 years to buy a sliver of America.

They turned over most of their meager earnings—$109 a month from Social Security plus rent from four tenants—for the three-story house at 412 Colvin St. in East Baltimore.

But when a city inspector tacked a notice to the door on Dec. 14, 1967, that the crumbling house was no longer safe to inhabit, the Turners discovered they didn’t own it at all.

According to a Baltimore Sun article published the day of their eviction, the couple had purchased their home with a “land-installment” contract, meaning through a property owner rather than a bank or mortgage company. The payments, ostensibly for the cost of the home, could instead be gobbled up by whatever fees the owner invented. Frank, 79, and Ethel, 67, paid more than $12,000 for rotting floors, grim advice from Legal Aid lawyers and dueling lawsuits with the property owners.

It was an inevitable end, written in 30-year-old red ink.

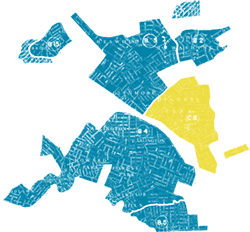

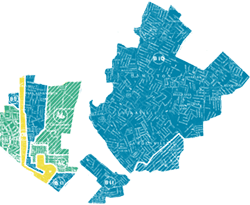

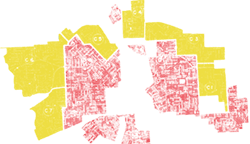

IN 1937, local real estate brokers and an economist helped federal officials evaluate each neighborhood in Baltimore to determine eligibility for home loans. On a sliding scale of worth, the Colvin Street area—along with most of the city’s core—was colored red, indicating hazardous for investment. The report noted negatives such as a “heavy concentration of foreigners” and “infiltration of Negro.”

These maps and reports were the foundation of “redlining,” which confined African Americans nationwide to specific neighborhoods outside the post-World War II housing boom. Without traditional avenues for home loans, black people were drawn into land-installment contracts and other pernicious methods that laid the groundwork for decades of poverty.

A new project by the University of Maryland’s College of Information Studies is bringing this material out of the historical shadows by creating a digital atlas of hundreds of Depression-era maps and reports that span thousands of neighborhoods. The Mapping Inequality initiative, says Richard Marciano, director of the Digital Curation and Innovation Center, will provide a new foundation in understanding how the racist policies of the past contribute to the inner-city problems of today.

“It’s a continuation of this historical hurt,” he says.

WHEN MARCIANO, an expert in digital archives and databases, moved to San Diego in the 1990s, he was curious about his neighborhood’s past. What people told him—that the area once had white occupancy requirements—pulled him into the dark side of American real estate. He collected original deeds for his Mission Hills subdivision and was amazed that racial restrictions from the early 1900s mirrored present-day trends. Eventually, he found that local bigotry had been institutionalized by the federal government through the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC).

Signed into law in 1933 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, HOLC was designed to boost the struggling real estate industry during the Great Depression. U.S. residential property construction had fallen by 95 percent, with half of all mortgages in default and more than 1,000 foreclosures a day.

Through HOLC and later programs in the Federal Housing Authority and Veterans Administration, the federal government helped refinance tens of thousands of homes and introduced the modern mortgage standard of smaller down payments and decades-long financing for homes meeting minimum building requirements. To guide its decisions, the government partnered with real estate officials around the country and drew maps to grade areas as green, blue, yellow or red.

HOLC and its descendant agencies were undeniably successful in expanding homeownership. By 1972, 63 percent of Americans lived in homes they owned, up from 44 percent in 1934. Embracing the romantic ideal of the countryside, the nation underwent a monumental shift to the suburbs, as industry collapsed in inner cities, developers snatched up cheap and plentiful land, and the federal government sank its resources into highway construction and loans for boxy houses planted in rows on the fringes of cities.

Baltimore peaked as the sixth-largest U.S. city in 1950, with about 950,000 people; in 2010, the city’s population had plummeted to less than 621,000. In those 60 years, Baltimore County’s ballooned from 270,000 to 805,000.

The HOLC maps dictated what parts of the country were—and weren’t— worth investing in. They put a premium on neighborhoods of single-family homes in all-white hands, with new construction and no evidence of African Americans. The directions for HOLC assessors considered “lower grade populations or different racial groups” as toxic as slaughterhouses.

THE THREE-STORY HOUSE at 1834 McCulloh St. appears unremarkable among other aging rowhomes in West Baltimore. But Antero Pietila, author of the 2010 book “Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City,” sees more than just a building.

“That,” he says, “is the turning point.”

In June 1910, black lawyer W. Ashbie Hawkins bought that home, crossing the city’s unofficial racial boundaries and setting off panic. Just six months later, Baltimore—at best, part of a grudging Union state during the Civil War—passed the nation’s first housing segregation law.

McCulloh Street, and its equivalents across the country, were only the beginning. As job opportunities grew in the North from world wars and Jim Crow discrimination stubbornly remained in the South, millions of black people left Florida fruit groves, Alabama cotton fields and Louisiana swamps for Washington, D.C.’s marble hallways, Chicago’s exploding industry and Los Angeles’ gleaming prosperity.

McCulloh Street, and its equivalents across the country, were only the beginning. As job opportunities grew in the North from world wars and Jim Crow discrimination stubbornly remained in the South, millions of black people left Florida fruit groves, Alabama cotton fields and Louisiana swamps for Washington, D.C.’s marble hallways, Chicago’s exploding industry and Los Angeles’ gleaming prosperity.

Yet through segregation, whether legal or off the books, poor black migrants were limited in their housing choices and restricted to run-down and redlined areas. In 1944, the Baltimore housing authority reported that the city needed to replace, renovate or build nearly 33,000 units to accommodate the black population.

But HOLC’s policies, which drove traditional banks and lenders away from African Americans, skewed the housing market. Speculators known as “blockbusters” brokered the sale of homes in white neighborhoods to black buyers—or just fomented the fear of it occurring—to buy properties cheaply.

“These were the original colored quarters,” journalist Isabel Wilkerson wrote in her 2011 history of the Great Migration, “The Warmth of Other Suns,” “the abandoned and identifiable no-man’s-lands that came into being when the least-paid people were forced to pay the highest rents for the most dilapidated housing owned by absentee landlords trying to wring the most money out of a place nobody cared about.”

Some parts of the country, like Detroit and Cicero, Ill., exploded into violence. Baltimore, with ample federal financing for white housing in the suburbs, simply emptied.

“There was no (white) resistance,” Pietila says. “There was just withdrawal.”

“There was no (white) resistance,” Pietila says. “There was just withdrawal.”

Although segregation ordinances like Baltimore’s were ruled unconstitutional in 1917, private racial covenants weren’t outlawed until 1948, and the federal government didn’t stop insuring developments with those restrictions for another two years.

So in September 1954, after losing her job, Hazel Collins and her elderly mother had to leave their house at 1028 East 20th St. in Baltimore. Collins, an African American, had purchased the home on a land-installment contract and poured her entire $3,000 in savings—plus the proceeds from pawning her furniture, television and kitchen stove—into a house that was never her own.

She was shackled to the home even after she left. Collins still owed money on the gas furnace, so she dutifully trekked to a loan office on Harford Road each Saturday to help pay for someone else’s heat.

According to a Baltimore Sun article, the home was worth nearly $12,000 in 1952. When last assessed in 2014—after decades of explosive growth in real estate prices—it was valued at $5,000.

HELENA HICKS PH.D. ’83 was born at 306 Presstman St. in 1934, the descendant of a long line of free blacks who came to this country as shipbuilders from France. Her father, William Sorrell, was a foreman at the National Biscuit Company and wanted to buy the family’s rented three-story house, with its marble steps, parlor and iron stove.

For William, “it was a Sorrell tradition that you own the roof over your head and the land under your feet,” Hicks says. Despite being part of the vibrant center of middle-class black life in Baltimore, the block was labeled by HOLC as riven by “obsolescence.”

“They wanted us out, period,” Hicks says. “They were not going to sell it to black people.”

In 1949, the family moved to Somerset Homes, a public housing project in East Baltimore, before eventually buying a home near Druid Hill Park, mere blocks from another redlined section. HOLC had warned that the neighborhood—colored yellow for its “declining” stature—was in danger of “negro encroachment,” and Hicks’ family watched as white neighbors fled. When she bought her own home in Baltimore’s Grove Park in 1963, it happened again.

Hicks still mourns the loss of her birthplace. Her family history of financial success and land ownership was not enough to outswim the redlining undertow.

“You destroy people’s sense of who they are when you take away something significant,” she says from the living room of the one-story brick home she has owned for more than 50 years. “It makes you angry because you know it didn’t have to be.”

Today, the house on Presstman Street is gone, and the site is a gateway to the wastelands of West Baltimore, the nexus of protests and turmoil in April 2015, where houses can crumble in high winds. To the southwest are Sandtown-Winchester and Harlem Park, with poverty and unemployment rates double Baltimore’s average, lead paint violations triple the average, and nearly a quarter of buildings standing vacant. Life expectancy there is only six months longer than in Ethiopia.

The 1968 Fair Housing Act outlawed any form of housing discrimination, including redlining, but in many ways came too late. With inner-city riots in the 1960s and economic stagnation in the 1970s, poverty begat more poverty. In his 2013 book “Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality,” sociologist Patrick Sharkey estimated that more than 70 percent of blacks “who live in today’s poorest, most racially segregated neighborhoods are from the same families that lived in the ghettoes of the 1970s.”

A March 2015 study by Demos found the median black household has just 6 percent of the wealth of a white one. Nearly one-third of that gap is attributable to disparity in homeownership and real estate investment returns: 73 percent of white households own their homes, compared to just 45 percent of blacks.

“It’s a sad story,” Hicks says. “It really is a sad story.”

MARCIANO IS PUTTING the HOLC database (a collaborative effort with Nathan Connolly of Johns Hopkins, Rob Nelson of the University of Richmond, LaDale Winling of Virginia Tech, and a team of UMD students) online so anyone can see “the definitive national map of neighborhood discrimination.” With documents digitized and overlaid with Google maps, researchers will see the legacy of redlining in their cities.

For example, Marciano found that public housing complexes in Asheville, N.C., are in the same areas that were redlined in the 1930s. His tool will make it easy for anyone to make such discoveries, and facilitate new projects that look at the interplay with everything from school test data to supermarket locations.

“The notion that redlining is dead,” Marciano says, “is ridiculous.”

Tags

Research