- May 09, 2023

- By Maggie Haslam

Forget “Jaws.” If you want a beach-themed scare this summer, look no further than the real-life horror show unfolding on the East Coast: a monstrous mass of seaweed the size of North America drifting toward the Florida coastline just as millions of Coppertone-slathered Americans plan their own descent on the Sunshine State.

But according to retired University of Maryland Associate Professor Patrick Kangas, the eye-grabbing headlines coming out of Florida are old news—by 533 years. First documented by Christopher Columbus (really!) in 1490, sargassum (which means “floating herbs” in Portuguese) has been a fixture on beaches around the Caribbean, Mexico and part of the U.S. for centuries, originating from a vast seaweed belt that occupies the middle of the Southern Atlantic.

What has changed is the quantity. Over the past decade, the U.S. and Mexico have seen a surge in sargassum washing up on beaches in knotty masses up to several feet deep, where it rots and emits an eye-watering sulfuric smell. This season’s crop—which is both early and prolific—has Florida hotels and resorts working overtime on costly, labor-intensive removal efforts.

“While this has been happening forever, we seem to have crossed some threshold,” said Kangas, from the Department of Environmental Science and Technology. “And this big, 5,000-mile patch is going to continue to feed the beaches. It’s a serious problem from a tourism standpoint.”

Should we be afraid (or even very afraid?) of sargassum sinking our seaside summer plans, or should we fearlessly unfurl our beach umbrellas? Kangas and University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES) Professor Victoria Coles untangle what we you should know about the abundant algae:

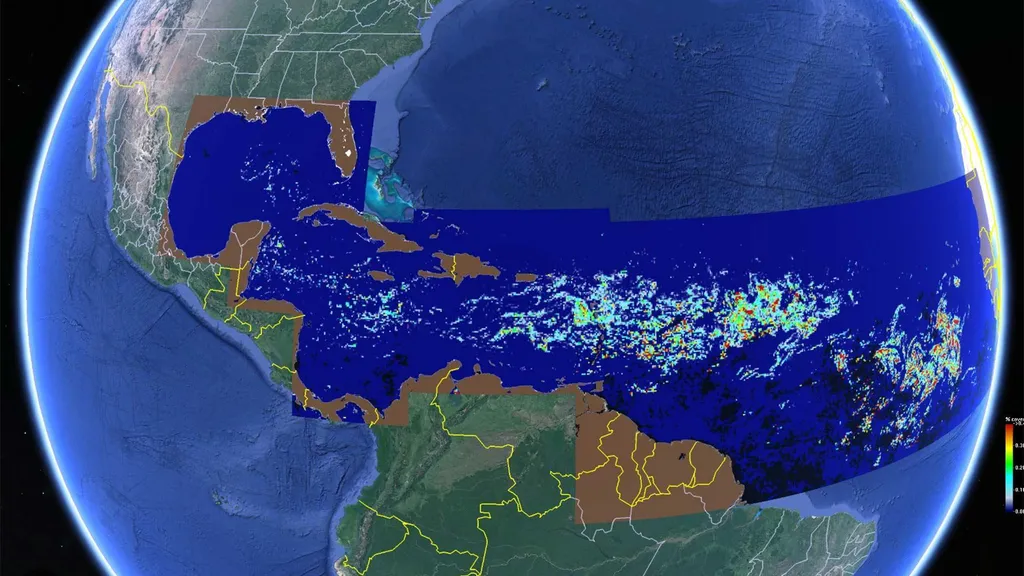

The sargassum patch is 5,000 miles in size—sort of. Despite some news reports, sargassum isn’t one giant blob on a collision course for Florida; rather a shapeshifting, thick “belt” of smaller beds—ranging from softball-size to miles-long masses—strung together. “If you were out there, you’d see that it’s patchy,” said Coles, who has studied interactions between physical and biogeochemical ocean processes for nearly 25 years at UMCES’ Horn Point Laboratory. “It’s not like you can walk on it for miles.”

It’s an ecological marvel in supporting oceanic life. Identified by its long branch structure, abundant, frilly leaves and oval berries, sargassum has evolved and thrived over centuries as a self-sustaining ecological community; it churns in a closed, spiral system called a gyre (similar to the garbage patches of the Pacific) and is kept afloat by special air bladders. It’s the only seaweed in the world that completes its entire life cycle floating on the surface and untethered to the bottom. While it may be a plague to beachgoers, it’s an oasis of food and habitat for an abundance of sea creatures, from fish and turtles to invertebrates and sea birds. “It’s gorgeous really, and a critical habitat for endemic species that only live in sargassum,” said Cole. “Humans just don’t like that it wrecks our vacations.”

No one knows why it’s growing—or breaking up—at a faster rate. Theories vary about why scientists began seeing an increase in sargassum in 2011. While some point to higher levels of nutrients in the water flowing from Africa, the Caribbean and South America, Maryland researchers favor another theory: Rising ocean temperatures and changes in trade winds and circulation patterns are pushing the blob into new areas it hasn’t previously appeared. “I think the timing this year has a lot to do with the seasonal patterns in the tropical Atlantic, which in turn impact ocean currents and how the sargassum moves and breaks apart,” said Coles, who along with Maureen Brooks M.S. ’03, Ph.D. ’19 has conducted both modeling and observational work on sargassum migration.

It could be an economy-booster and a secret weapon against climate change. Algae has historically been used for a variety of purposes; once decomposed, it is an incredible fertilizer, particularly for beach ecosystems; used as livestock feed, some algae have shown to produce less methane. The influx of sargassum, said Kangas, has also spurred discussions about how to keep it from reaching the beach in the first place, either harvesting it with trawlers for biomass—a potential new economy—or sinking it deep in the ocean where it can’t decompose and release greenhouse gases—a modest method of carbon sequestration.

It won’t harm you, but other algae might. Sargassum is not toxic to people—more a tangled mess. Other ocean-borne algae, like red tide, can cause sometimes-fatal illnesses. Fauna of all kinds, as well as trash people have dumped in the ocean, said Kangas, are increasingly showing up on both U.S. coasts. “People love to go to the beach. But we have to realize that our world is changing, and we’ll need to adapt.”