- October 18, 2021

- By Josh Land And Annie Krakower

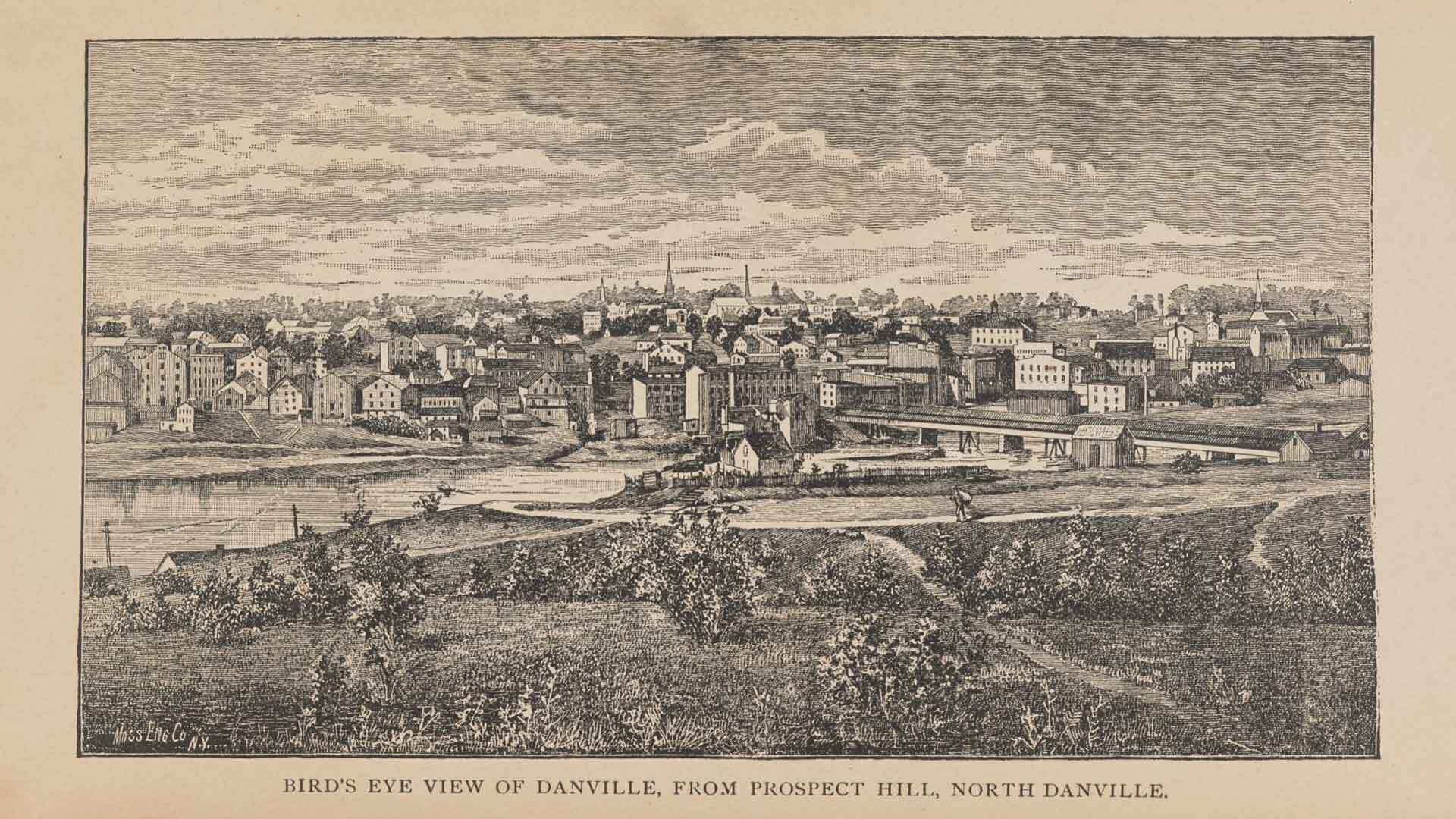

In the days leading up to the 1883 state election in Danville, Va., an armed white mob took to the streets, killing six Black men and threatening others who left their homes to cast their vote.

After the first night of the violence, when four were murdered, a Richmond Dispatch article declared, “These negroes had evidently come to regard themselves as in some sort the rightful rulers of the town. They have been taught a lesson.” In the local Danville Times, the main headline didn’t condemn the massacre, but rather celebrated the white Democrats’ election win: “GLORIOUS VICTORY!”

The racial hate fueled by the coverage is just one example that students at the University of Maryland and partner schools explored as part of a collaborative Howard Center for Investigative Journalism project launching today online. The investigation, “Printing Hate,” delved into dozens of white supremacist-run newspapers from the end of Reconstruction to 1965, revealing how racist headlines and stories spurred racial tensions, lynchings and other violence. Newspapers were America’s most powerful news medium for the majority of that period.

The Howard Center will publish more than 30 stories on the subject on Mondays and Thursdays throughout the fall, with the articles appearing on Capital News Service’s Howard Center website, the National Association of Black Journalists’ news site and Word in Black, a collaboration of the nation’s leading Black news publishers.

“This is a timely reckoning,” said Howard Center Director Kathy Best. “Who better to hold newspapers to account for their racist coverage in the past than the journalists of tomorrow?”

In addition to Terps from the Philip Merrill College of Journalism, the Howard Center recruited students from historically Black colleges and universities—including Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, Morgan State University and North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University—and the University of Arkansas to further diversify the reporting corps and include the perspectives of students living in the South, where many of the incidents covered in “Printing Hate” occurred.

The team, inspired by Associate Professor of journalism and Washington Post writer DeNeen L. Brown’s reporting on the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, spent the spring, summer and fall digging into archives and interviewing descendants, historians and other experts to document the power of white-owned newspapers to harm the Black community—and the findings could make for uncomfortable reading.

“The student journalists have been courageous in their research and reporting in pursuit of the truth. Working on this project ... was at times painful,” Brown said. “I hope the readers would be as courageous.”

To supplement the writing, the students analyzed data, shot photos, recorded audio, created graphics, designed a website and built a news application that will allow people to explore historical lynching coverage by approximately 100 newspapers that still exist in some form today.

“They were looking for really egregious examples of coverage that used language that portrayed victims of lynchings or of massacres as less than human,” Best said. “Words like ‘brute’ and ‘fiend’—and those were the nicer words.”

The group also analyzed the role of Black-owned newspapers at the time, such as The Chicago Defender or The Afro-American in Baltimore. Such papers would send their own reporters to Southern cities to see what really happened, Best said, often providing a counternarrative.

Throughout the project, the students were guided by four visiting professionals—retired Washington Post editors Milton Coleman and Deborah Heard, former Los Angeles Times and St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter Ron Harris, and Washington poet and lawyer CeLillianne Green—as well as faculty and staff from UMD and Arkansas.

“One of the truisms in the world is those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” Best said. “I hope that these stories will create an opportunity for conversation about how what happened in the past may be influencing what’s happening today.”

Topics

Research