- October 01, 2018

- By Liam Farrell And Chris Carroll

Once the shooting had finally stopped and she was bloodied but safe in a hospital, all Rachael Pacella ’13 wanted was a pen and paper. She was confused and in pain, but she was still a journalist—she had to write all of this down.

The Capital reporter’s day on June 28 had started in typical overscheduled fashion: She covered Induction Day ceremonies for new midshipmen arriving at the U.S. Naval Academy, then rushed to a press conference outside of Annapolis for a story about recent deaths on local waterways.

By 2:30 p.m., Pacella was back at her desk writing and about to email photos from the press conference when a shotgun blast shattered the office’s glass front door.

The gunman—allegedly a reader with a grudge against the newspaper and two journalists who hadn’t worked there in years—then stepped inside and killed five Capital Gazette employees: John McNamara ’83, a longtime Terps sports reporter; Gerald Fischman ’79, the editorial writer; Rob Hiaasen, an editor and adjunct professor at UMD; Wendi Winters, a features writer; and Rebecca Smith, a sales assistant. Pacella was one of six employees in the newsroom that afternoon who survived.

The Capital Gazette murders—possibly the single deadliest incident for journalists in American history—have prompted difficult questions about the value of local news, squeezed for years by financial problems, and a national narrative that has often cast journalists as villains.

“On the next day, we probably had eight different journalists come through to interview me and other people here … and they told me how they used to feel safe going on stories, doing a standup on the street corner,” says Lucy Dalglish, dean of the UMD Philip Merrill College of Journalism. “But now, on just ordinary, run-of-the-mill stories, citizens are yelling at them, throwing things at them, breaking up their live shots, and in other ways basically disparaging them, and it’s very scary.”

Yet there has also been strength in just continuing the mission. Capital reporter Chase Cook quickly tweeted after the shooting that “We are putting out a damn paper tomorrow”—and they did.

Meanwhile, Pacella, who was treated for a concussion and cuts she’d suffered trying to flee the gunfire, eventually got a pen and paper and scribbled down everything she remembered and saw in front of her: the name of her doctor, the shape of the blood drying on her arm, how the newsroom had smelled like gunpowder, the make and model of the camera used to photograph her injuries.

And Pacella kept on writing, in notebooks and on a new blog documenting her recovery. Her trade became a comfort and motivation in the weeks after her life was changed forever, through vigils and funerals, quiet trips to museums and hikes in the woods.

“I want to capture and remember every piece of it,” she says. “I don’t think it will affect the kind of stories I write. If anything, it motivates you to move forward in a better way.”

At a vigil near the Capital Gazette office the day after the shooting, one of the paper’s most senior reporters, E.B. “Pat” Furgurson III, implored the crowd to recognize the humanity behind the bylines.

“We are not the enemy,” he said. “We are you.”

In the immediate outpouring of grief and support from around the country—including a network of former Capital employees volunteering their help, back-ordered “Press On Annapolis” T-shirts and a memorial fund raising more than a half-million dollars—it appeared that people agreed with Furgurson.

But for a long time, the media and American public have drifted farther and farther apart. People jeer “lock them up” at penned reporters covering political rallies and President Donald Trump disparages journalists as “enemies of the people” almost daily with charges of peddling “fake news.” Just a day before the Annapolis mass shooting, right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos said that he looked forward to vigilantes “gunning down journalists.” He later said he was joking.

The disdain cuts through U.S. society: According to a 2017 Knight Foundation-Gallup study, Americans believe 39 percent of the news reported by newspapers, TV and radio is “misinformation”—intentional fabrications, or stories that can’t be verified but are reported as fact.

Adding to the gloom are the internet-driven declines in circulation and advertising revenue that have led to the gutting of newsrooms nationwide, along with continuing consolidations and closures. Across the country, from 2005–17, the number of reporters and correspondents plunged 42 percent.

This dynamic has been particularly destructive at smaller newspapers like The Capital, as its shrinking staff tries to meet the demands of filling pages and the 24-hour news cycle online. Owned by Philip Merrill, namesake of UMD’s journalism school, from 1968 until 2007, it’s since changed owners several times, switched from afternoon to morning delivery, and sold its printing press. The building where the attack took place is a shared office complex two miles from the newspaper’s former sprawling home.

Gavin Buckley, the mayor of Annapolis, said in the wake of the shooting that The Capital is the sort of publication where you go to find “reports on our kids’ sports games.”

“This paper is not a left-wing paper, it’s not a right-wing paper, it’s just a great local paper that we all love,” he said. “To be that offended is just unfathomable.”

Local newspapers help to hold communities together, says Dalglish, a national voice on media issues. They are where people learn why taxes are going up and who is getting an award at their child’s school.

“If we lose this,” she says, “I think communities are going to come unglued.”

Safety, however, has now risen to the top of the list of problems. Merrill College plans to undertake a new effort to teach journalists around the country how to handle disgruntled readers and viewers.

“How do you recognize the difference between someone who’s angry and rational,” Dalglish says, “versus angry and dangerous?”

The accused shooter—Jarrod W. Ramos, a Laurel, Md., resident who had unsuccessfully sued the newspaper for defamation—was clearly the second.

After he started firing at her co-workers, Pacella initially hid under her desk, then ran toward the back door. She tripped and slammed her face into the door frame before discovering that it wouldn’t open; the shooter had barricaded it from the outside. Bleeding profusely, she crouched between two nearby filing cabinets. She was convinced she was going to die, until she didn’t.

In those endless seconds, Pacella says, her mind spun around the question of why someone would target The Capital and kept landing on the answer that the country’s anti-journalist sentiment had finally boiled over.

“Any reasonable person will at least ask the question,” she says. “I don’t think we have an answer.”

Fewer than 24 hours after Pacella said that, Trump tweeted about his summit in Helsinki with Russian President Vladimir Putin, calling it “a great success, except with the real enemy of the people, the Fake News Media.”

After staggering through the initial period of shock and mourning, Merrill College and the university are considering how to honor and permanently memorialize the lost Terps: McNamara, Fischman and Hiaasen.

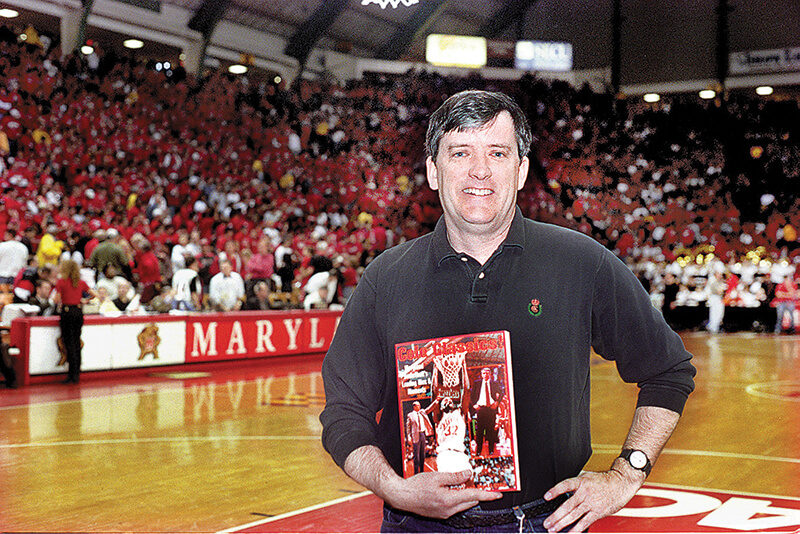

McNamara, whose funeral was held at Memorial Chapel, met his wife, Andrea Chamblee ’83, while they were students at UMD and had covered Terps football and basketball since his days as a Diamondback staffer. The respect he commanded far outweighed the modest circulation of the newspaper he wrote for.

“The first thing I noticed about John was how much he loved the game of basketball,” says former basketball coach Gary Williams ’68. “He was one of those people you could feel close to and still have a business relationship with.”

His encyclopedic mastery of Terps basketball culminated in his 2001 book “Cole Classics! Maryland Basketball’s Leading Men and Moments,” written with Dave Elfin. He followed up in 2009 with “The University of Maryland Football Vault: The History of the Terrapins.”

Staff cuts and reorganizations at Capital Gazette Newspapers eventually had McNamara shift to covering two local communities. Local news wasn’t his first love, but he approached it as seriously as he did sports, often reporting late into the night at government meetings and cultivating relationships with his best sources. In his free time, he was finishing a new book about the history of basketball in D.C.-area high schools.

Longtime friend Doug Dull ’81, a former associate athletic director at UMD, remembers how McNamara came calling on him in intensive care in early 2017, when he was fighting a sepsis infection and slipping in and out of consciousness.

“My sister-in-law told me the story that John nonchalantly walked in and said he needed to bring me up to date on what’s going on in the sports world,” Dull says. “He talked about the Terps, talked about the Capitals, talked about a few other teams. What struck her was how normally he treated it.”

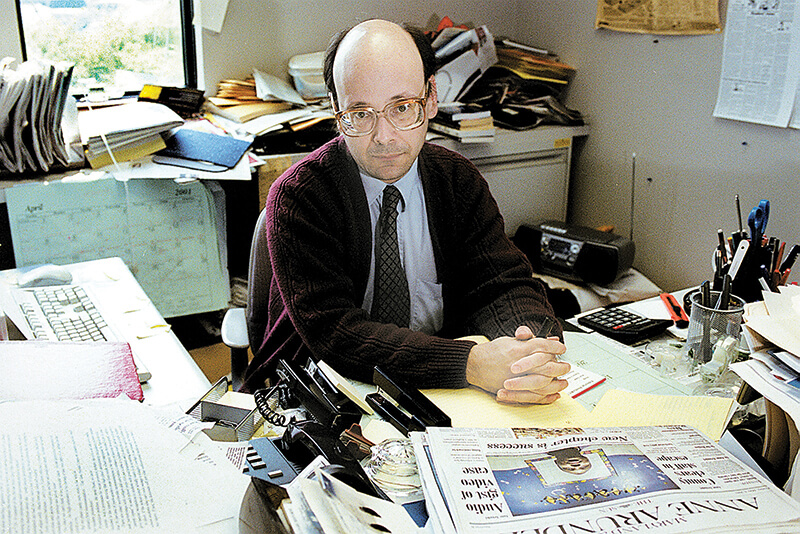

Fischman ’79, who also worked for The Diamondback, was an award-winning editorial writer who began working at The Capital in 1992. Known for his cardigans, late hours and introverted personality, he would leave pointed, clear-eyed drafts on reporters’ desks each morning, accompanied by Post-It notes politely asking to check them for accuracy.

Professor Emerita Maurine H. Beasley, who taught Fischman, says he made a strong impression on her as mature and well read. She wasn’t surprised he became an editorial writer.

“He had a great understanding of current events and was the kind of person who could see both sides of an issue,” she says.

Hiaasen, who taught news writing and reporting last spring at Merrill College and was scheduled to do so again this fall, started working at The Capital in 2010 after 15 years as a feature writer at The Baltimore Sun. Friends and co-workers recalled his gentle, supportive style as an editor, epitomized by encouraging notes and voicemails he’d leave them praising a nicely written piece, or gently inquiring about the status of an article.

“I don’t think I ever saw him without a smile on his face,” says Abell Professor Sandy Banisky, who worked with Hiaasen at The Sun, where she previously was deputy managing editor.

Senior Lecturer Chris Harvey ’80 spoke with Hiaasen frequently as he navigated his first semester as an adjunct lecturer. She says he was a natural, brimming with enthusiasm.

“He loved coming in here,” she says. “He had a gift for helping people … and bringing them up to the next level.”

Eager to help in any small way, faculty have been filling in as editors at The Capital’s temporary Annapolis newsroom. Officials will name a classroom in Knight Hall, home of the journalism school, in honor of the five Capital Gazette employees who were killed. Maryland Athletics intends to install permanent seat placards bearing McNamara’s name on press row at Xfinity Center and Maryland Stadium, along with memorial plaques in the media rooms.

A new community-funded scholarship for Merrill students had raised $133,000 at press time, and Hiaasen’s family established another journalism scholarship at Maryland.

Weeks after the shootings, four crosses and a Star of David still stood in front of the building with The Capital’s abandoned newsroom. American flags and fresh bouquets of flowers had been placed around them. A police car was stationed in front.

At a coffee shop in historic downtown Annapolis, the city had fallen back into a more regular rhythm. People ate breakfast wraps, sipped coffee and pecked at laptops. A lobbyist held court at one table, discussing some grand strategy. A family of tourists wandered in.

Pacella, whose fingers fight and pick at each other as she talks and pauses to think, interned at The Capital in 2013 and spent the next four years angling for a full-time job there. She got her chance in spring 2017 after a few years at The Daily Times in Salisbury and community newspapers in Baltimore County and, after spending her childhood near Ocean City, is glad to be close to the water again.

She compares the decision to become—and stay—a reporter to buying a boat: It’s not the best financial decision, and guarantees hardships along the way, but you don’t have much choice if you can’t live any other way.

“It just gives you a license to have this weird curiosity. I would miss all of that in my life,” she says. “I can’t be happy without it, so I’m going to stick with it.”

In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, she salved her trauma by playing card and board games with friends and watching the talk show parody “Comedy Bang! Bang!” But there was also what she termed “terror roulette,” where a car horn might not bother her at all, but the sound of a trunk slamming or something being dropped in a neighboring apartment could send her into paroxysms of fear, collapsing to the ground into a clump of tears and screams.

“Those issues aren’t gone,” she says, but adds: “They’ve gotten better.”

As of mid-July, Pacella had no specific timeline for going back to work. Once she does, she’s hoping to expand into photography and videography, and maybe get back to covering environmental issues.

“I’m looking forward to finding more cool people to write about,” she says. “Don’t know who, but there will always be somebody.”

Liam Farrell was the state government reporter at The Capital from 2007–11.

Photos courtesy of The Capital/Baltimore Sun Media Group