- January 12, 2016

- By Chris Carroll

For most of us, snow is simple stuff, and guessing about school cancellations or how long it’ll take to shovel the driveway is about as complicated as it gets.

But for Barton Forman (right), snow measurements open the door on a world of complexity where even the special shapes of individual snowflakes—multiplied trillions of times—can factor unpredictably into the crucial question he’s trying to answer.

With the help of NASA satellites and UMD supercomputers, the assistant civil and environmental engineering professor is developing methods to quantify the earth’s total supply of snow—a giant frozen reservoir that provides freshwater to about one-seventh of the human race.

Like many aspects of the natural world these days, snow is threatened.

“It’s the primary drinking water supply for more than a billion people—mostly in the northern hemisphere, including the U.S.,” Forman says. “But as the world is getting warmer, snow is disappearing. It’s shifting poleward, and it’s also moving up the mountain, effectively looking for colder ground.”

He says that while El Nino-driven floods and mudslides have hit parts of California this winter, the state has been parched for the past several years because of the lack of snow. Winter after winter of subpar mountain snowpack led to devastating drought in heavily populated but dry areas, and forced farmers in the world’s most productive agricultural region to deplete groundwater.

Snow is just as crucial in parts of the world where—unlike in California’s Sierra Nevada range—there’s no reliable on-the-ground method to measure how much frozen water is stored at high altitudes. Simply looking at snow coverage from orbit can’t take thickness or density into account—variables affected by factors ranging from snowflake shape to how much melting and refreezing has occurred.

“We simply don’t know how much snow is out there,” he says. “It’s really dynamic. It changes in space and time.”

Supported by a NASA New Investigator Award, Forman’s snow study uses two complimentary satellite-based techniques.

The first relies on measurements of microwave radiation emitted by the earth. Snow scatters the radiation, allowing investigators to infer how much water it contains. Others substances complicate matters.

“The satellite measures all emitted microwaves, and they can originate from the ocean, from sea ice, vegetation, soil moisture,” he says. “Figuring out what part of that signal is truly related to snow is a complex process.”

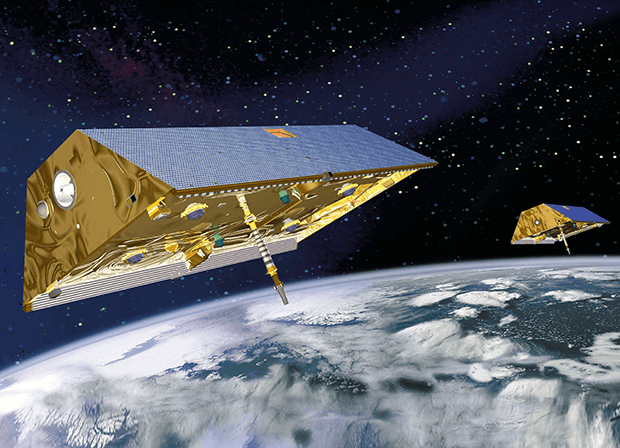

Forman also uses gravity anomalies to gauge snow cover. NASA’s GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) orbiters sense minute variations in the earth’s gravitational field over wide areas, allowing researchers to effectively observe snow building up and melting.

“That mass is moving,” he says. “Imagine you have a mountain, and then it gets covered in snow, which is a lot of mass. The gravitational field will change.”

There’s more to it than just taking measurements. Forman is using UMD’s Deepthought2 high performance computing cluster to crunch massive amounts of data as he works toward an overarching computer model of global snow.

His method involves machine learning, a field in which computers are programmed to learn and make predictions, and neural networks, where groups of computer models inspired by brain functions work together, says a NASA collaborator.

“Basically, you teach the computer to infer non-linear relationships given training data” from satellite snow observations, says Rolf Reichl, a research physical scientist in global modeling and assimilation at the NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center. “Once you’ve trained the machine, you give it new data it hasn’t seen before and it will estimate the snowpack.”

When Forman has reached his goal and can tell you how much snow is in the world by typing in a command or two, he won’t have stopped global warming or saved the depleting snow.

But accurate forecasts will be a major advance as climate scientists and water resource planners try to ensure the tap doesn’t run dry for a large portion of humanity.

“We want to understand and preserve this important resource,” he says. “A fundamental question we need to answer is, exactly how much of it is there?”

Tags

Research