- September 18, 2020

- By Maggie Haslam

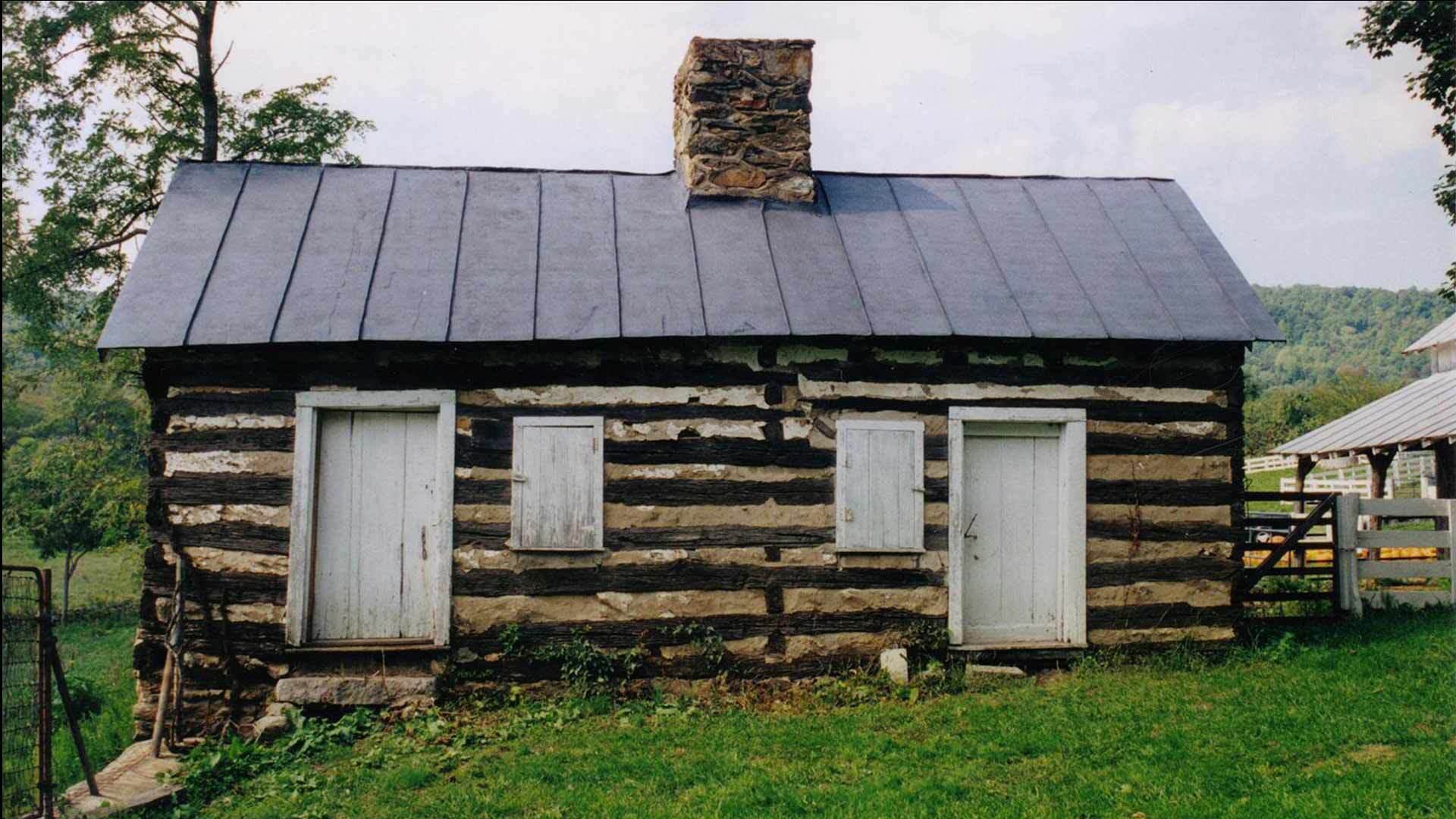

In the shadows of the stately mansions and sprawling farmsteads of Virginia are hundreds of small, ramshackle, weather-beaten buildings: the former slave dwellings of pre-Civil War America.

Dennis Pogue is making the case to save them.

For the past 20 years, Pogue, an adjunct associate professor of historic preservation at the University of Maryland, and colleague Professor Doug Sanford, from the University of Mary Washington, have assessed over 100 former slave quarters in the commonwealth and gathered information on hundreds more. A growing database of their work, thought to be one of the first concerted efforts to document and preserve these structures in the South, is now available online through UMD’s Historic Preservation Program.

“Our goal is to gather information on these buildings before they are lost, but it’s also an active pursuit of preservation,” said Pogue. “We hoped that by paying attention to these buildings, we’d get other people to pay attention to them too.”

“Our goal is to gather information on these buildings before they are lost, but it’s also an active pursuit of preservation,” said Pogue. “We hoped that by paying attention to these buildings, we’d get other people to pay attention to them too.”

Pogue’s work is an extension of a 25-year career at Mount Vernon, the home of George Washington, where he worked as an archeologist and, later, as a museum administrator. While Pogue was instrumental in the restoration of Washington’s mansion, the grist mill, distillery and other structures, his first project was the site of a slave house, an excavation that yielded what is now one of the largest collections of artifacts associated with 1700s-era slavery. Pogue’s work jumpstarted a comprehensive program around the lives of Washington’s enslaved people, including the re-creation of slave quarters.

“It was truly an archeologist’s dream,” he recalled of excavating the site. “We were able to recover old ceramics, glass, tobacco pipes, food remains. That experience was a big motivator in increasing the interpretation of slavery at Mount Vernon. With something that tangible, you can really tell interesting stories.”

It also sparked an interest in tracing the lives of enslaved people beyond Washington’s gates. It was soon evident that there was no systematic documentation of their dwellings.

On weekends and in during breaks from teaching, Pogue and Sanford began discovering more of them, often obscure, neglected and forgotten on the edge of properties. At one point, Pogue estimates there were tens of thousands of such structures, and those that survived are often close to the main house. The proximity has led to situations of extensive alteration by the property owner, often into a guest or pool house, a garden shed or, in one case, a poker parlor.

“We leave judgment at the door, because these people are allowing us onto their property,” said Sanford. “Oftentimes, they don’t know what to do with them, and we really have to make a case for preservation; that it’s an important building that should be preserved and not turned into a clubhouse for their grandkids.”

That argument hasn’t always come easy. Repairing and preserving these structures can be expensive. Many are on working farms, where the owners have little money to dedicate to preservation.

Pogue also explained that confronting the physical evidence of the darkest part of American history has conjured a spectrum of emotions. After Mt. Vernon erected spaces that were directly evocative of slavery, Pogue recalls some visitors voicing discomfort or guilt. But for the most part, Pogue said, the people with dwellings on their property have shown interest in finding a way to preserve them once they understand the historic value.

“These buildings are divisive,” he explains. “They hold difficult, painful stories. And right now, we’re contending with a lot of issues that revisit these same themes. The White House and the Capitol building are also slave buildings—they were built by slaves. But it’s in these places that the story becomes more visible because it’s where these folks’ lives actually occurred. So that makes them all the more important.”

Pogue and Sanford have collaborated with organizations including Encyclopedia Virginia, a project by Virginia Humanities, to research and identify the people who lived in these dwellings and bring their stories to light, and to develop virtual tours of numerous slave houses. The UMD database offers details of each structure, a collection of pictures and immersive Google street view tours of the interior and exterior of each structure.

“The places that Dennis and Doug document aren’t available to the general public because of their location or condition, so being able to virtually walk through and experience these places makes them impossible to ignore,” explains Peter Hedlund, director of the Encyclopedia Virginia project. “There’s a misconception that slave houses are relegated to these big sprawling plantations in Virginia, but you’ll find them behind brownstones in downtown Richmond or Alexandria. Slavery was a pervasive institution, it was everywhere. Through their work, Dennis and Doug are preserving a narrative that might otherwise be forgotten.”

Pogue and Sanford have worked with a half-dozen owners to repair and preserve structures and are hoping to raise seed money to help other property owners in similar efforts.

“I’m a strong believer in places,” said Pogue. “They have an impact that you can’t get from reading history in a book and these buildings are a critical part of the American story.”