- January 17, 2017

- By Chris Carroll

The crown jewel of Matthew Kirschenbaum’s collection, or maybe just the most hulking piece of it, occupies a corner in the basement of Hornbake Library. It’s a few hundred pounds of beige Cold War-era machinery, with cryptic buttons and knobs and a vaguely menacing air, like something for dialing in ballistic missile target coordinates.

The crown jewel of Matthew Kirschenbaum’s collection, or maybe just the most hulking piece of it, occupies a corner in the basement of Hornbake Library. It’s a few hundred pounds of beige Cold War-era machinery, with cryptic buttons and knobs and a vaguely menacing air, like something for dialing in ballistic missile target coordinates.

The first dedicated device ever marketed for a then-revolutionary activity called “word processing,” IBM’s Magnetic Tape/Selectric Typewriter, or MT/ST, wasn’t designed for mass destruction. Instead, its arrival in 1964—meeting with the kind of fanfare reserved today for new iPhones—would transform the landscape for writers around the world.

In Kirschenbaum’s recent book, “Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing,” the associate professor of English and director of UMD’s graduate certificate in digital studies uncovers how the MT/ST and its successors captured—and even changed—the imagination of authors, upended modern offices, tweaked stereotypical gender roles and digitally altered the fundamentals of writing.

“Writing by hand or sitting at a typewriter, we’re always in the present moment, going character by character, line by line,” he says. “Word processing allowed writers to grasp a manuscript as a whole, a gestalt. Everything was instantly available via search functions. Whole passages could be moved at will, and chapters or sections reordered. The textual field became fluid and malleable.”

These new powers depended on the machines—from Osbornes to Brothers to Apples—many of which Kirschenbaum has up and running in the Hornbake Library office of the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities. “It’s not about nostalgia,” he says, but so he and colleagues can access and preserve manuscripts or old interactive fiction written on forgotten operating systems and dead technologies. What not so long ago seemed futuristic was in danger of being lost to history, so Kirschenbaum set out to document it.

Pioneers Beyond Pens

Who wrote the first book on a word processor? The question helped fuel Kirschenbaum’s research, and the answer depends on what you consider a word processor and how you define “wrote.” At a price of $10,000 in 1960s money, early machines were designed for offices, not individual users.

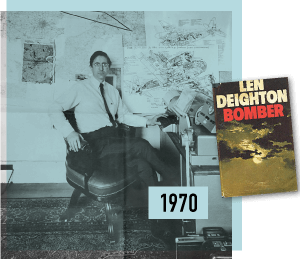

One of the few who could afford his own was popular British novelist Len Deighton, who used the MT/ST for his 1970 book, “Bomber.” But Deighton still wrote on a typewriter, handing off pages to his assistant to retype into the unwieldy machine’s magnetic tape storage. She then added Deighton’s revisions without retyping whole sections, accelerating the process.

The first novel written on a word processor in the modern sense—with the author herself composing and revising entirely on a computer screen—might have been Gay Courter’s 1981 historical bestseller, “The Midwife.” She used a 1977 IBM System 6 that she and her husband had bought for their documentary film company, finding snippets of time amid work and family responsibilities to write fiction. Her writing method wouldn’t have been possible without the efficiency of the machine, she told Kirschenbaum. When she turned in her manuscript, “the agent was fascinated with the cleanliness of the copy, the justified type… Part of the in-house buzz was because of the word-processed MS.”

The first novel written on a word processor in the modern sense—with the author herself composing and revising entirely on a computer screen—might have been Gay Courter’s 1981 historical bestseller, “The Midwife.” She used a 1977 IBM System 6 that she and her husband had bought for their documentary film company, finding snippets of time amid work and family responsibilities to write fiction. Her writing method wouldn’t have been possible without the efficiency of the machine, she told Kirschenbaum. When she turned in her manuscript, “the agent was fascinated with the cleanliness of the copy, the justified type… Part of the in-house buzz was because of the word-processed MS.”

Deleting Drudgery

Now that it’s old hat, it’s easy to forget how much tedium word processors freed us from in the late 20th century. Office workers rejoiced, as did popular fiction writers who discovered that the new technology facilitated the high level of productivity they needed to earn a living. While many “serious” authors of literary fiction initially turned up their noses (Gore Vidal declared the machines were “erasing literature”), those who embraced word processors left behind smeared correction fluid, dead typewriter ribbons, jumbles of pages and endless retyping of revisions. “Boy, has this thing made it easier to write science fiction,” author Jerry Pournelle wrote in a computing magazine in 1979. “It was hugely freeing,” cyberpunk pioneer William Gibson told Kirschenbaum. “Typographical errors were now of no import, and text became literally plastic with cut-and-paste.”

Now that it’s old hat, it’s easy to forget how much tedium word processors freed us from in the late 20th century. Office workers rejoiced, as did popular fiction writers who discovered that the new technology facilitated the high level of productivity they needed to earn a living. While many “serious” authors of literary fiction initially turned up their noses (Gore Vidal declared the machines were “erasing literature”), those who embraced word processors left behind smeared correction fluid, dead typewriter ribbons, jumbles of pages and endless retyping of revisions. “Boy, has this thing made it easier to write science fiction,” author Jerry Pournelle wrote in a computing magazine in 1979. “It was hugely freeing,” cyberpunk pioneer William Gibson told Kirschenbaum. “Typographical errors were now of no import, and text became literally plastic with cut-and-paste.”

The Writer's Brain

Word processing did more than change the physical processes of writing—it gave writers new ways to think about their works in progress, even taking on some of the mental load they’d had to carry themselves in the day of typewriters. Novelist Stanley Elkin said the Lexitron VT 1303 that he dubbed the “bubble machine” relieved him of having to remember exactly what he’d devised 200 pages earlier. As a result, “the word processor has facilitated not just the mechanics of writing but has actually facilitated plot… (I)t occurs to you, gee, wasn’t there some kind of reference to that earlier on? So you put the machine in search mode, and you find what the reference was earlier, and you can begin to use these things as tools, or nails, in putting the plot together.” After resisting for years, Salman Rushdie finally began using word processing software in the 1990s and immediately understood why others had found it so useful: “Just at the level of writing, this is the best piece of writing I’ve ever done… I’ve been able to revise much more.”

Word processing did more than change the physical processes of writing—it gave writers new ways to think about their works in progress, even taking on some of the mental load they’d had to carry themselves in the day of typewriters. Novelist Stanley Elkin said the Lexitron VT 1303 that he dubbed the “bubble machine” relieved him of having to remember exactly what he’d devised 200 pages earlier. As a result, “the word processor has facilitated not just the mechanics of writing but has actually facilitated plot… (I)t occurs to you, gee, wasn’t there some kind of reference to that earlier on? So you put the machine in search mode, and you find what the reference was earlier, and you can begin to use these things as tools, or nails, in putting the plot together.” After resisting for years, Salman Rushdie finally began using word processing software in the 1990s and immediately understood why others had found it so useful: “Just at the level of writing, this is the best piece of writing I’ve ever done… I’ve been able to revise much more.”

Redefining Roles

The term “word processor,” like “typewriter” before it, originally referred not to a machine or a computer program, but to a person—typically a female office worker trained to operate the machinery, Kirschenbaum says. Because gender has always loomed large in modern workplaces, it’s a key element in the history of word processing as well.

The New York Times observed at the advent of the MT/ST, “The International Business Machines Corporation introduced yesterday a typewriter that it believes will eliminate a lot of the drudgery of a secretary’s job. It will also eliminate a lot of secretaries.” But a feminist-toned ad for an IBM competitor in the debut issue of Gloria Steinem’s Ms. magazine was grimly celebratory about “The Death of the Dead-end Secretary: It’s been long overdue.” Word processing, the ad promised, would allow women to move out of typing pools into positions of greater authority.

The New York Times observed at the advent of the MT/ST, “The International Business Machines Corporation introduced yesterday a typewriter that it believes will eliminate a lot of the drudgery of a secretary’s job. It will also eliminate a lot of secretaries.” But a feminist-toned ad for an IBM competitor in the debut issue of Gloria Steinem’s Ms. magazine was grimly celebratory about “The Death of the Dead-end Secretary: It’s been long overdue.” Word processing, the ad promised, would allow women to move out of typing pools into positions of greater authority.

Whether word processing actually helped as more women moved into management is an open question, but it did end the association of typing with “women’s work.” As Kirschenbaum says, “It was soon so easy, even guys could do it.”

Process Complete

Word processing was so effective at easing many of the demands of the writing process that it firmly embedded itself in homes and businesses throughout the world over the course of a few decades. But paradoxically—unlike the early days of the IBM MT/ST—the term is hardly used anymore. Instead we type, touch, swipe and even talk to our devices, while “text” has become a verb, Kirschenbaum says.

Word processing was so effective at easing many of the demands of the writing process that it firmly embedded itself in homes and businesses throughout the world over the course of a few decades. But paradoxically—unlike the early days of the IBM MT/ST—the term is hardly used anymore. Instead we type, touch, swipe and even talk to our devices, while “text” has become a verb, Kirschenbaum says.

“Word processing is something we once did, in the same way we once used dial-up modems and studiously hyphenated the triple alliterative of the World-Wide Web,” he writes. “Nowadays we mostly just write, here, there and everywhere, across ever increasing multitudes of platforms, services and surfaces.”

Word processing’s triumph was that it allowed writers, more than ever before, to focus not on the process or on tools, but on the text. TERP

Photos courtesy of Kirschenbaum