- August 30, 2018

- By Chris Carroll

While tick-borne diseases increasingly take a toll on people, a unique UMD-led project will examine how ticks themselves respond to infections.

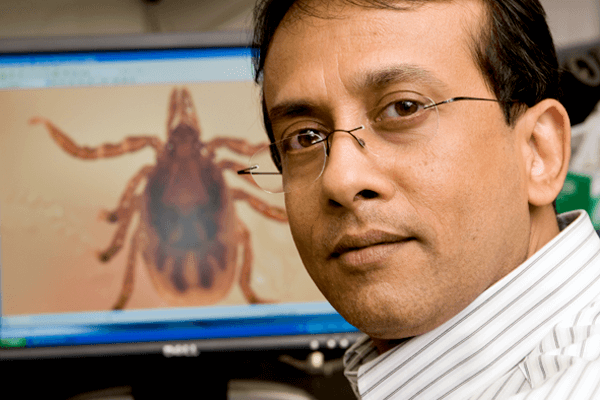

Funded by a $7.7 million, five-year grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the project led by veterinary medicine Professor Utpal Pal will focus on the immune response of black-legged ticks to the bacteria that cause Lyme disease and anaplasmosis.

The study’s multi-institutional team includes researchers from the University of Maryland, Baltimore, the University of Minnesota Twin Cities and Yale University.

“This is the first large program to look at how this particular arthropod vector—the black-legged tick—controls and suppresses the pathogen before it transmits it,” Pal says.

According to U.S. Centers for Disease Control report from May, rates of tick- and insect-borne infections nearly quadrupled from 2004 to 2016, with Lyme disease the primary driver of the increase. And although many Lyme cases aren’t reported, the CDC estimates around there are 300,000 a year.

The broad aim of the new grant is to increase knowledge of tick immune function and help develop strategies to fight tick-borne illnesses, Pal says. It could also spur additional research that translates into specific new therapies for people infected with two bacterial pathogens—Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophilum—which infected ticks can pass along when they latch on for a blood meal.

The project is based partly on previous research in which Pal’s team disabled a key part of the tick immune system and found that pathogen loads skyrocketed by a factor of 10 or more. It showed that ticks’ immune systems could suppress invading microbes like the one that causes Lyme disease. Although the bacteria don’t seem inherently harmful to ticks, the bloodsuckers probably fight them to control their numbers and conserve needed nutrients, Pal says.

In another experiment, he found that ticks’ immune systems seem to be able to ramp up when necessary.

“What we discovered was that the tick takes signals from the infected host… and when a ticks feed on a blood meal from a host, it can tell, “Hey, I have an infected blood meal, not a healthy one,” and then limit pathogen levels with a microbicidal compound, he says.

One innovative aspect of the research will be a focus on how the tick microbiome—the microorganisms that inhabit the creatures—impacts the species’ immune system.

“The microbiome piece will help us tell us why there is a different tick immune response in different geographical regions,” he says. “Why does the ability to control pathogens vary in different locations?”