- April 17, 2025

- By John Tucker

Inside a University of Maryland lab, Jordan Lieb ’26 spit into a tube in hopes of learning more about herself.

After adding chemical agents to the saliva, she placed the tube into a whirring centrifuge, extracting her DNA from her cells. The tube now rests in a freezer, but in the coming days she and her classmates will make billions of copies of a DNA section, part of an effort to draw conclusions about her ancestral origins.

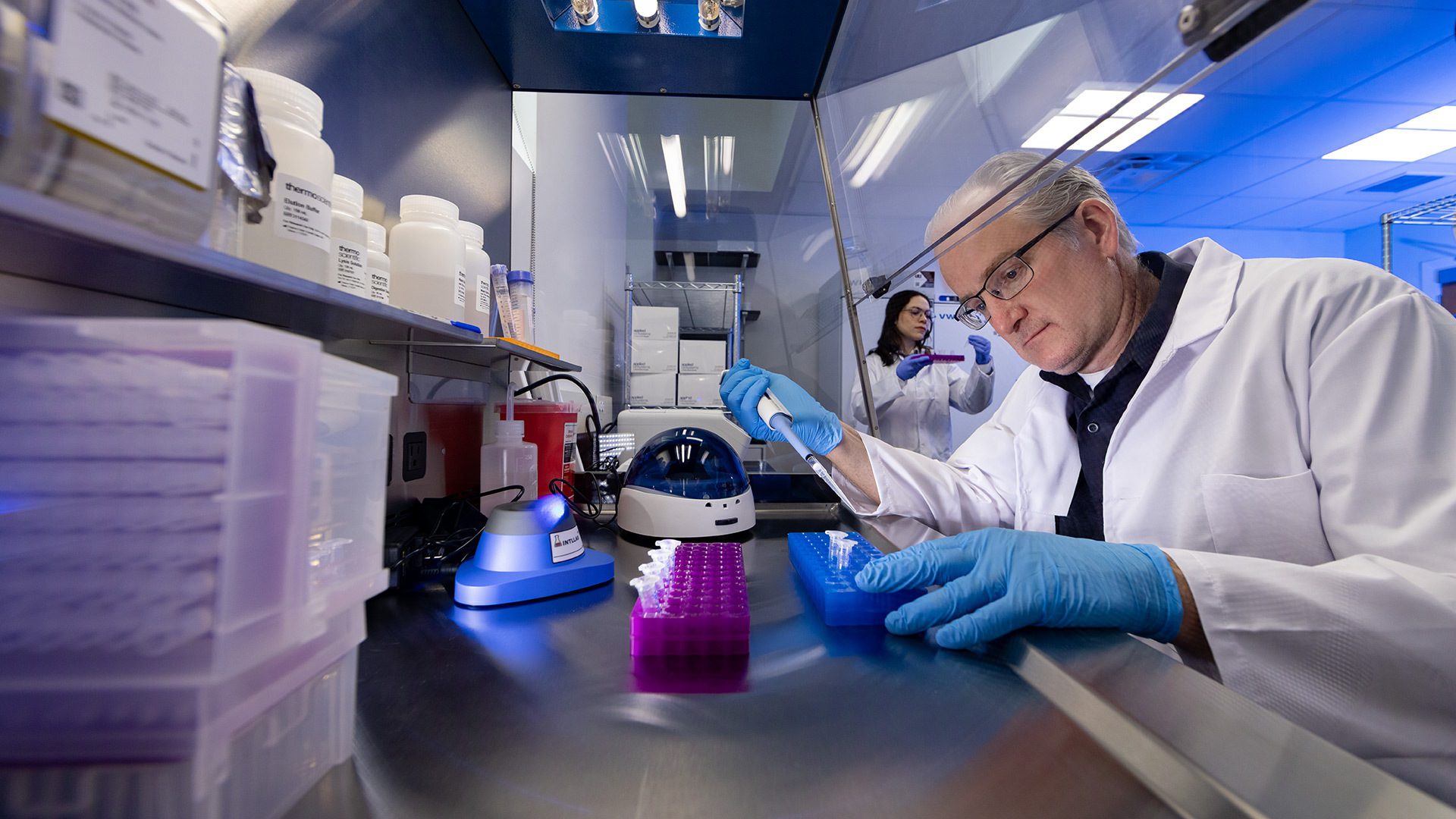

Last week marked the unveiling of the lab, the first of its kind in the state. Dedicated to the rapidly growing field of genetic anthropology, its researchers use DNA to trace the evolution and migration of human groups from ancient times to the present.

While most of us associate DNA tracing with family trees and companies like ancestry.com, anthropologists were swabbing cheeks well before the human genome was decoded in 2003. A biologist or geneticist might look at DNA to understand its structure and function; anthropologists use it to compare person A with person B, then try to trace their ancestors from hundreds and even thousands of years ago to develop a deeper understanding of human history and ethnography.

When Lieb, an anthropology major, learned of the lab last semester, “it sounded so fascinating because I knew I wanted to be more on the natural sciences side of anthropology,” she said. Lieb will use the facility to continue analyzing the mitochondrial DNA of Koreans, tracking their migration to the peninsula from East and Central Asia.

“For students, it has the feel of a citizen-science class, with interactive teaching tools,” said the facility’s creator, Assistant Professor of anthropology Miguel Vilar. With table space to accompany 12 students, “it’s really a classroom inside of a lab. That’s always been the vision.”

The facility boasts sparkling equipment, unpackaged just weeks ago: a fluorometer, which uses quantum technology to determine whether DNA samples are sufficiently concentrated; a thermocycler, which relies on thermal energy to makes billions of copies of single DNA strands, forming a mass large enough to study; and an electrophoresis machine, which uses electric charges to isolate genetic biomarkers linked to anthropological traits like, say, malaria resistance.

Fernanda Breckenfeld Ferrarini, a first-year master’s-doctoral student from Brazil, said the lab influenced her decision to enroll, because she’ll have a chance to apply her biotechnology background to human culture in what she called an “academic hub” where diverse projects are related by a unifying idea: “This is the study of all of us somehow,” she said. “Even if I’m looking at populations other than mine, it’s all DNA related to the human species, it’s all genes that I also have.”

Vilar, a global leader in genetic anthropology, remains active with his fieldwork. In the Bahamas, for example, his team is currently tracing the path of enslaved Ahanta people from Ghana, apparent ancestors of current residents, forced to work the islands’ sugarcane farms. Earlier in his career, he compared maternal and paternal DNA from 326 donors in Puerto Rico, leading to grim findings that Spanish men killed off the Indigenous men and often impregnated the surviving women.

During frequent research trips to Guam, locals jokingly greet Vilar as “my long-lost brother from across the world!” He hails from Puerto Rico, another island whose history includes centuries of Spanish and U.S. colonization, though their populations are genetically distinct.

Later this year, Vilar will open a second lab to study “ancient DNA,” which is extracted not from saliva, but fossil remains. While some anthropologists study human bones dating to a time when Neanderthals shared the planet with early modern humans, Vilar’s students will begin with 15th century sheep and cattle bones and teeth, unearthed from Iceland by UMD departmental colleagues. The tracing of livestock DNA will shed light on what 600-year-old populations ate, and Vilar’s team plans to eventually move on to ancient human DNA.

The ancient DNA lab will adopt strict measures to prevent contamination from DNA shed from students’ skin, hair or breath. Reverse-pressured air-filtration systems will be installed, along with ultraviolet lighting that will kill ambient DNA left by visitors. Students and other lab workers will don hazmat-like suits covering them from head to toe.

Before joining UMD, Vilar directed National Geographic’s pioneering Genographic Project, collecting and cataloguing more than 1 million DNA samples before companies like 23andMe gained steam. During the late 2010s, he helped grow the field into “next-gen” sequencing, where the number of traceable genetic distinctions in a human genome jumped from hundreds of thousands to tens of millions.

But some of Vilar’s biggest contributions to the field are happening outside of the lab, where he works to counter a lack of cultural and geographic diversity among genetic anthropologists, despite the focus on multiethnic identities and colonial history. Meanwhile, most researchers are from elite schools and organizations in the U.S. and Western Europe.

“As a Latin American who grew up in the shadow of the U.S., I thought that this amazing field shouldn’t be limited to the U.S. or a small group of people; it should be shared by the world,” said Vilar. “These nations have people who know and want to tell their own stories but lack the resources to create labs.”

As the field transitioned from modern to ancient DNA tracing, Vilar sought out museum curators and archaeologists from Latin America, Africa and Asia, helping them secure grants to study their fossils. Thanks in part to those efforts, labs have since cropped up in Mexico, India and China.

Michael Pateman, a Bahamian curator and archaeologist with British and African roots, is among Vilar’s mentees. After Vilar helped recruit him into a collaboration with Harvard University’s DNA lab, they launched a Bahamian lab, studying forced migration to the archipelago from Africa, Hispaniola and Cuba.

“Miguel has helped me with a big part of my career,” said Pateman, who was recently appointed as a Bahamian government ambassador.

At UMD, Vilar is excited about infusing the field with young talent, as well. Undergraduates deserve research opportunities alongside postgrads, he said.

Anthropology major and lab assistant Sarozini Shrestha ’28 is grateful for the inclusion.

“A lot of students struggle their first few years because of their perceived inexperience,” she said. “I’m lucky that Dr. Vilar wants to work with us.”

All through April, Maryland Today will celebrate how the University of Maryland is reimagining learning and teaching. Find more stories at today.umd.edu/topic/we-reimagine-learning.

Topics

Research