- February 17, 2020

- By Samantha Watters

For decades, researchers have sifted through the soil under free and enslaved African Americans’ homes and the kitchens, farms and fields where they worked to recover pottery, tools and trinkets that might illuminate their experiences. But new research led by a lecturer in UMD’s Department of Environmental Science and Technology takes a unique approach: examining the makeup of the soil itself.

Candice Duncan teamed up with Howard University to analyze grave soil samples collected decades ago from the New York African Burial Ground, the largest African burial ground in the country. Their pioneering work, featured in Nature Scientific Reports, used hard soil chemistry, a discipline not commonly combined with anthropology. It detected high levels of arsenic, copper and zinc in the soil, suggesting the site was being used as a dumping ground by local kilns and pottery factories, while the presence of artifacts could indicate that freed African slaves worked in those trades.

“We know a lot of the history of how Africans came here to the U.S. and the injustices in that process, but when they got here and after they were freed, it’s nice to know how they survived,” Duncan said. “What did they eat? How did they live? What trades were they doing? The collection at Howard could give us pieces to that puzzle, and maybe one day we will get a complete picture, which is currently a gap in African American heritage.’”

“We know a lot of the history of how Africans came here to the U.S. and the injustices in that process, but when they got here and after they were freed, it’s nice to know how they survived,” Duncan said. “What did they eat? How did they live? What trades were they doing? The collection at Howard could give us pieces to that puzzle, and maybe one day we will get a complete picture, which is currently a gap in African American heritage.’”

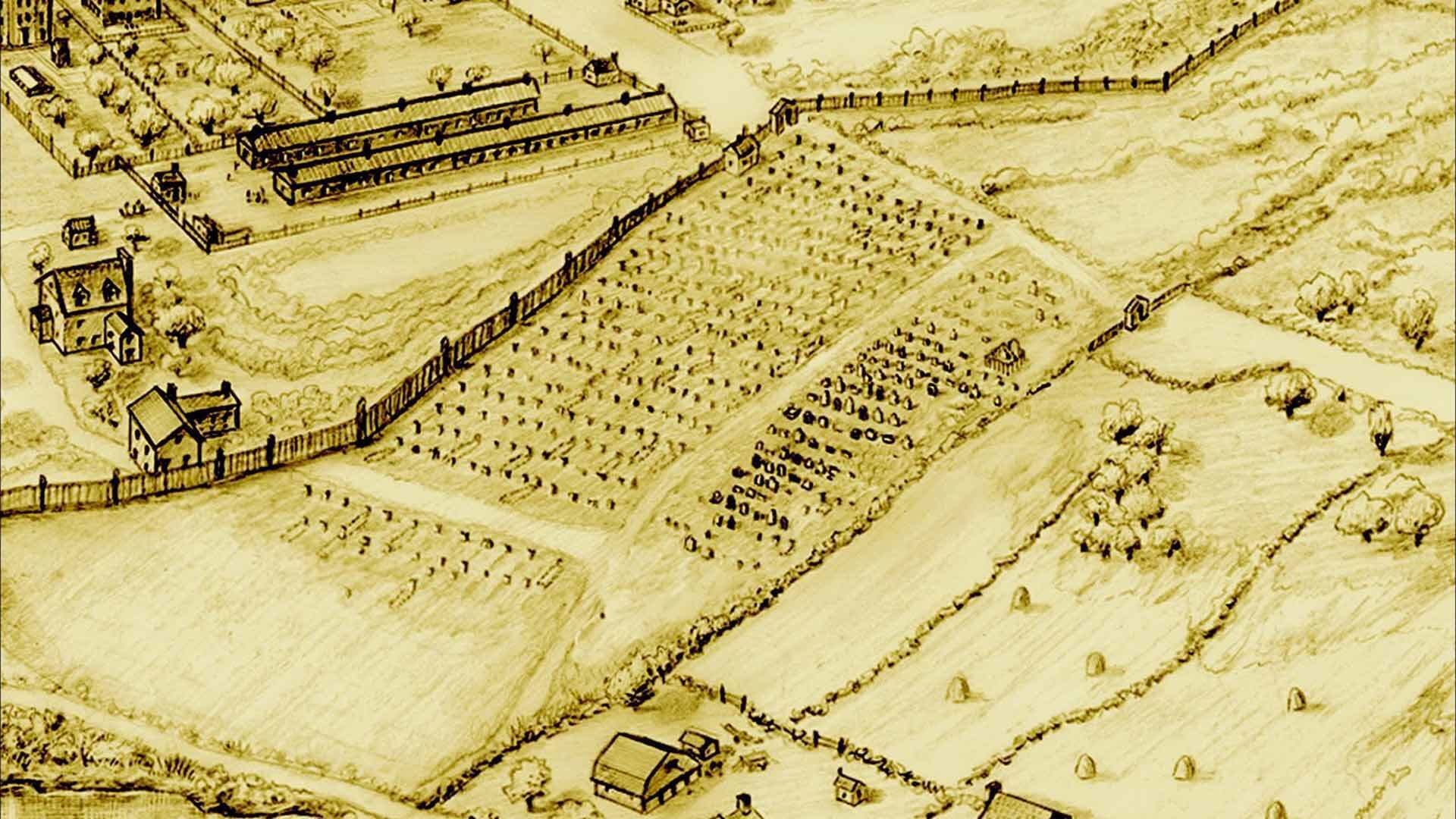

The six-acre burial ground on what is now Broadway in Lower Manhattan was used as far back as the 1630s, and contains more than 15,000 intact skeletal remains, according to the National Park Service, which now oversees the site. It was rediscovered in 1991 during excavation for a federal office tower, and researchers began to take samples from the site to study the skeletal remains. The remains were later reinterred at the site, and Howard University now houses the full collection of soils and artifacts uncovered there.

Carter Clinton, assistant curator at Howard’s W. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory and a doctoral candidate in biological anthropology, leads the research on the grave soil samples. He and Duncan conducted the soil analyses in the UMD lab of Ray Weil, professor and renowned soil scientist, using portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry to detect the trace metals in the soil, including high levels of strontium.

“The interesting thing is when you see these elevated levels of strontium in human remains, it’s an indicator of a vegetative diet,” common among poor and enslaved African Americans, said Clinton. He is also looking at bacterial DNA and microbial compounds in the soil, the geospatial mapping of the soil and bioethical components of how all of these data come together to tell a complete story.

Using biological and dental analysis, researchers at Howard have already gone a long way in filling in the gaps in the biological history of African Americans, uncovering the age of remains, life expectancy, and making inferences about where these inhabitants came from.

Using biological and dental analysis, researchers at Howard have already gone a long way in filling in the gaps in the biological history of African Americans, uncovering the age of remains, life expectancy, and making inferences about where these inhabitants came from.

“Reconstructing these data gives us real insight into what life was like back then,” said Fatimah Jackson, UMD professor emerita who now directs the W. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory and leads this project and Clinton’s doctoral committee.

The team hopes to do more in-depth chemical analysis on the samples to learn more about the people buried at this site, confirm preliminary findings and connect this with chemical analysis of bone and artifact samples.

“I look at the whole collection of samples as an information chip in time, and we are decoding to get a story from it,” Duncan said. “Long term, I see it giving us a lot of information about enslaved, now free, Africans being able to have a say in their true history.”