- February 12, 2014

- By Liam Farrell

In the early spring of 1946, a University of Maryland professor and a Polish exile traveled to a manor in the fairy-tale forests of lower Bavaria to see what dark secrets were hidden in its walls.

Over two days at Schloss Zandt, a 14th-century house about 125 miles northwest of Munich, Harold J. Clem and Maj. Karol Estreicher searched for pieces needed to rebuild a culture nearly extinguished by the Nazis in World War II.

They discovered about 10,000 books in the manor, each with markings from the Institut für Deutsche Ostarbeit, or Institute for German Eastern Studies. The organization, founded in 1940 in German-occupied Poland, had taken over offices in a university where many professors were sent to their deaths in a concentration camp. The institute was researching a racial and cultural hierarchy in Europe—in the words of Clem’s March 27, 1946, report—“for the purpose of rooting out Polish art and culture.”

“But, at the same time,” he wrote, “almost every book contains the marking of some department of Cracow University, and which the Germans had not removed.”

The trove at Schloss Zandt, which also included Polish carpets, paintings, laboratory equipment and chemicals, was just part of the Nazis’ campaign to remake Europe in preparation for a new thousand-year rule. These artifacts were tracked down following the war’s upheaval and bloodshed by hundreds of men and women in the Allies’ Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) section, and their work is being honored in the new George Clooney movie “The Monuments Men.”

As described by Robert M. Edsel in his book of the same title, the effort to assess damaged buildings and artifacts, recover pieces hidden from advancing armies and reclaim the more than five million cultural objects seized by the Germans—including paintings by da Vinci and Rembrandt and sculptures by Michelangelo and Donatello—was initially overseen by only a dozen people in the months following D-Day.

Eventually, about 350 men and women from 13 nations would serve in the effort to reclaim the heritage of the battered continent. And one of them, Harold J. Clem, was a Terp.

Culture at Gunpoint

About 13 years before Clem went to Schloss Zandt, Adolf Hitler celebrated his 44th birthday by attending a play at the State Theatre in Berlin. The play, Schlageter, celebrated German resistance to French occupation following World War I, and featured arguments about the primacy of race and country over the individual pursuits of the arts and intellect.

“When I hear ‘culture,’” one character says, “I release the safety catch of my Browning!”

This piece of dialogue, as described by Richard J. Evans in “The Coming of the Third Reich,” came to summarize the Nazi attitude toward art.

As Evans notes, the country’s struggles following its defeat in World War I were accompanied by cabaret shows, Bauhaus bohemians, jazz and sensationalist tabloids that became symbols of a degenerate, decaying social order far removed from the triumphs of Wagner and ascribed to the influences of Jews and Bolshevism.

The Nazi arts program took two paths: One was the systematic removal—or worse—of dissident and Jewish artists from their positions, the creation of Nazi propaganda and overt destruction of books and art through burnings.

The other path involved appropriation. Hitler, famously rejected from a Vienna art school, had designs on remaking European culture and turning his hometown of Linz, Austria, into the new artistic center of the world with a Führermuseum housing its most important works of art.

Culture was endangered, then, not only by war’s bullets, bombs and profiteers, but also by ideology.

“The mad grandeur of the whole thing, which envisaged nothing less than a complete redistribution and reorganization of Europe’s people and their patrimonies, is impressive,” wrote Lynn H. Nicholas in “The Rape of Europa.” “ … Everything would be magnificently organized, efficient, and clean, classified and arranged in the gleaming new cities, to the Glory of Germanism.”

The prospect of losing some of the most valuable artifacts of human history prompted American and other Allied leaders to start the MFAA.

The Monuments Men who saw Europe during combat were short on resources, and sometimes, as in the case of decimated cities like Saint-Lô in France, too late. But they had successes, including the discoveries of Rothschild jewels at Neuschwanstein Castle, and Michelangelo’s “Madonna and Child,” Jan van Eyck’s “Ghent Altarpiece” and Vermeer’s “The Astronomer” in the salt mines of Altaussee, Austria.

A Life in Documents

Whether by choice or because he was just one part of a mammoth, generational effort, the story of Harold J. Clem must be told without his voice. His remarkable journey from Maryland classrooms through war-torn Germany is pieced together through government records, archives and obituaries.

He died in December 1996 at age 87, and according to the obituaries in The Baltimore Sun and Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, Clem was survived by wife Ruth Pauline Davis Clem and son Harold D. Clem, who Terp was unable to contact.

The obituaries paint a picture of a rising academic. Clem taught English and history at Mount Airy High School, joined the Hood College faculty in 1936, and became an assistant professor of history at Maryland in 1943.

Clem is found in two faculty-staff directories in the University Archives, for the years 1943–44 and 1944–45. Schedules of classes show he taught “Survey of Western Civilization,” “Europe of the 19thCentury, 1870–1914” and “Revolutionary and Napoleonic Europe.”

While information on his time at UMD is sparse, papers in the National Archives create a collage of Clem’s Monuments Men service.

He joined the MFAA branch as a civilian archivist on Sept. 9, 1945, and was sent to the Eastern Military District near Munich for a temporary assignment. On Nov. 15, Clem reported on his initial attempts to secure the Bavarian War Archives and Munich Kreisarchives, or circulars, describing them as scattered “among castles, churches, monasteries, parsonages, and private dwellings.” He said 33 truckloads, or 70 tons, of Bavarian archival material were salvaged from a prisoner-of-war camp, and eight truckloads of Munich material (“scattered among 25 churches and monasteries”) were brought to the Oberammergau Collecting Point—two former research buildings of the Messerschmitt aircraft manufacturer, near the modern-day Austrian border.

Whatever work Clem managed to do there, however, was lost. Illustrating how reconstruction efforts were not immune from the fog of war, he and an officer wrote a Jan. 17, 1946, letter detailing how the archives’ documents had been transferred to a stable by prisoners of war, with files pushed down chutes into trucks or scattered and trampled in the snow.

“They have entirely lost the scientific classification and arrangement which had been achieved through the efforts of trained archivists and their assistants during the past three months, and are no longer properly protected,” Clem wrote.

Within the next month, his job had been taken to the field. He found Russian and possible Dutch books at Staffelstein and Schloss Banz; he questioned a German family in jail and returned to Munich with nearly 400 Roman coins (he notes the family was subsequently released); he inspected a library at Schloss Tan and found a baroness who claimed she had no idea where her books had come from.

Clem earned praise from his peers. Oliver W. Holmes, a program adviser, sent a July 1946 letter to Maj. Lester K. Born of the MFAA saying Clem was “enthusiastic but level-headed and dependable, and surely has his feet on the ground.”

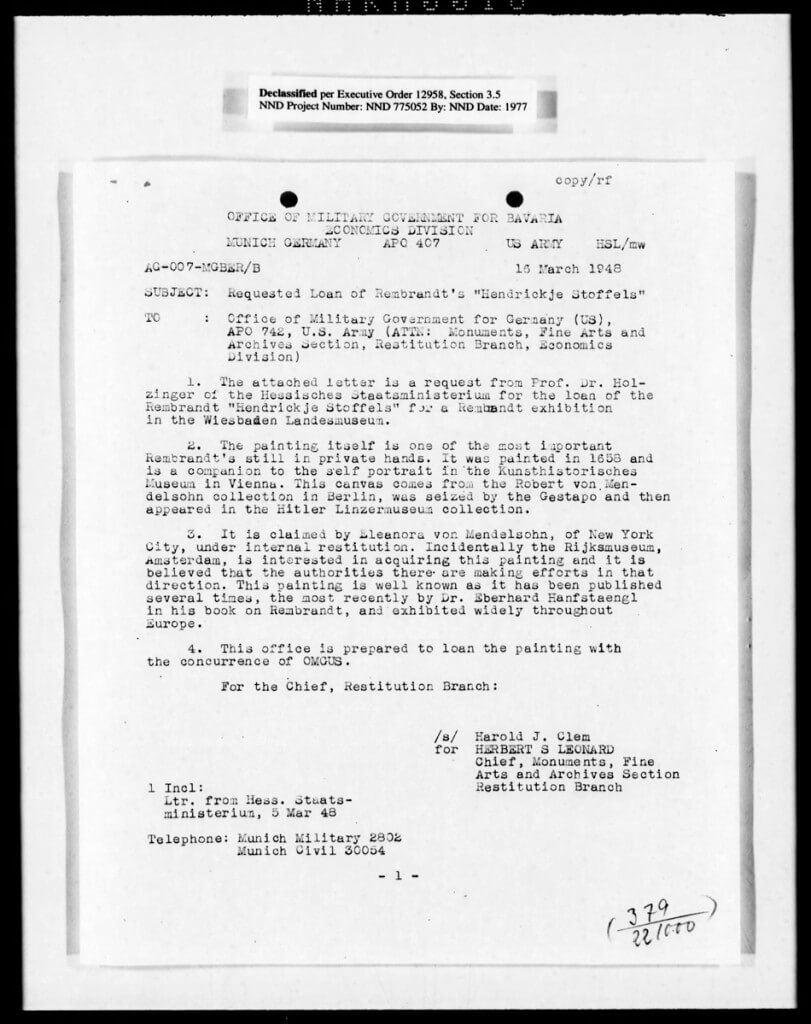

Sometimes, his work involved interrogating his own countrymen. In March 1948, Clem inspected the Officers’ Club in Lenggries Kaserne and found 12 chairs that belonged to the Bavarian royal palace. A certain Lt. Col. Kelleher told him “he found the chairs in the Officers’ Club when the 18th Infantry took over … and had no further knowledge of the origin of the chairs.”

Clem arranged for a representative of the Munich Fine Arts Collecting Point to pick them up.

Finding the Past

Those who work to save history, however, can disappear inside it.

Clem ended his work with the Monuments Men in 1948, then worked as a political advisor to the U.S. Commission for the State of Bavaria from 1949–52. He taught political science to senior military officers at the National Defense University until his retirement in 1975. He wrote textbooks that can still be purchased online.

The Monuments Men Foundation has no information about Clem except his name, and has spent the past seven years attempting to complete biographies and obtain photographs for each member of the group.

Biographical information is not the only thing missing. The Foundation also has a list of artwork that remains unfound, including works by Botticelli, Monet, Degas and El Greco. A tip line (1-866-WWII-ART) is still operational.

Nearly 69 years removed from the end of World War II, the inexorable march of the present has hidden some of the more quotidian corners of the conflict and the reconstruction that followed. Schloss Zandt, the site of some of Clem’s larger finds, was purchased by the Bavarian Red Cross in 1949 and has operated ever since as a nursing home. Today, it boasts a chapel, a cafeteria, a large orchard with a pond, and a library—one with a much different purpose. TERP