- February 05, 2021

- By Don Markus

Darryl Hill had already spent two years playing college football when he was approached by an up-and-coming Maryland assistant coach who heard the Navy plebe was looking to transfer. Lee Corso wouldn’t take ‘No’ for an answer.

It was the spring of 1962 and Corso had been told by Terps coach Tom Nugent to find him a candidate talented and tough enough to become the first Black player at a predominantly white school in the South.

Though he grew up idolizing Jackie Robinson, Hill told Corso he wasn’t interested in being a trailblazer.

“I said, ‘Look coach, I’m not trying to be Jackie Robinson, I just want to play football,’” Hill recalled this summer. “He said, ‘You must be scared. You’re afraid, huh?’ That was the button that he pushed that got my attention. He got me with that one.”

“I said, ‘Look coach, I’m not trying to be Jackie Robinson, I just want to play football,’” Hill recalled this summer. “He said, ‘You must be scared. You’re afraid, huh?’ That was the button that he pushed that got my attention. He got me with that one.”

Nearly six decades later, the now popular ESPN analyst clearly remembers the approach he took trying to lure Hill to College Park. At the time, Hill was planning on taking visits to Penn State, Syracuse and Notre Dame.

“I knew that I could challenge him. If I could challenge him, I could get him to do it,” Corso said in an interview.

Corso knew that Hill had also been the first Black football player at Gonzaga High in Washington, where he had won an academic scholarship despite being two years younger than his classmates and where he led the team to a city title as a senior. Corso knew that Hill was about to become Navy’s first Black varsity athlete as well had he remained at the academy.

Just as Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey had researched Robinson’s background thoroughly before signing the UCLA football star to break major league baseball’s color line in 1947, Corso did the same with Hill. He learned that Hill’s father owned an independent trucking company and Hill’s mother was a schoolteacher in D.C.

“Darryl Hill was the perfect candidate to be the first Black player [at Maryland],” Corso said. “First of all, he was intelligent, you could see that because he had gotten into the academy. And he wasn’t afraid of a challenge. That was very important. As great a football player as he was, he had the right temperament. He wouldn’t let things bother him too much.”

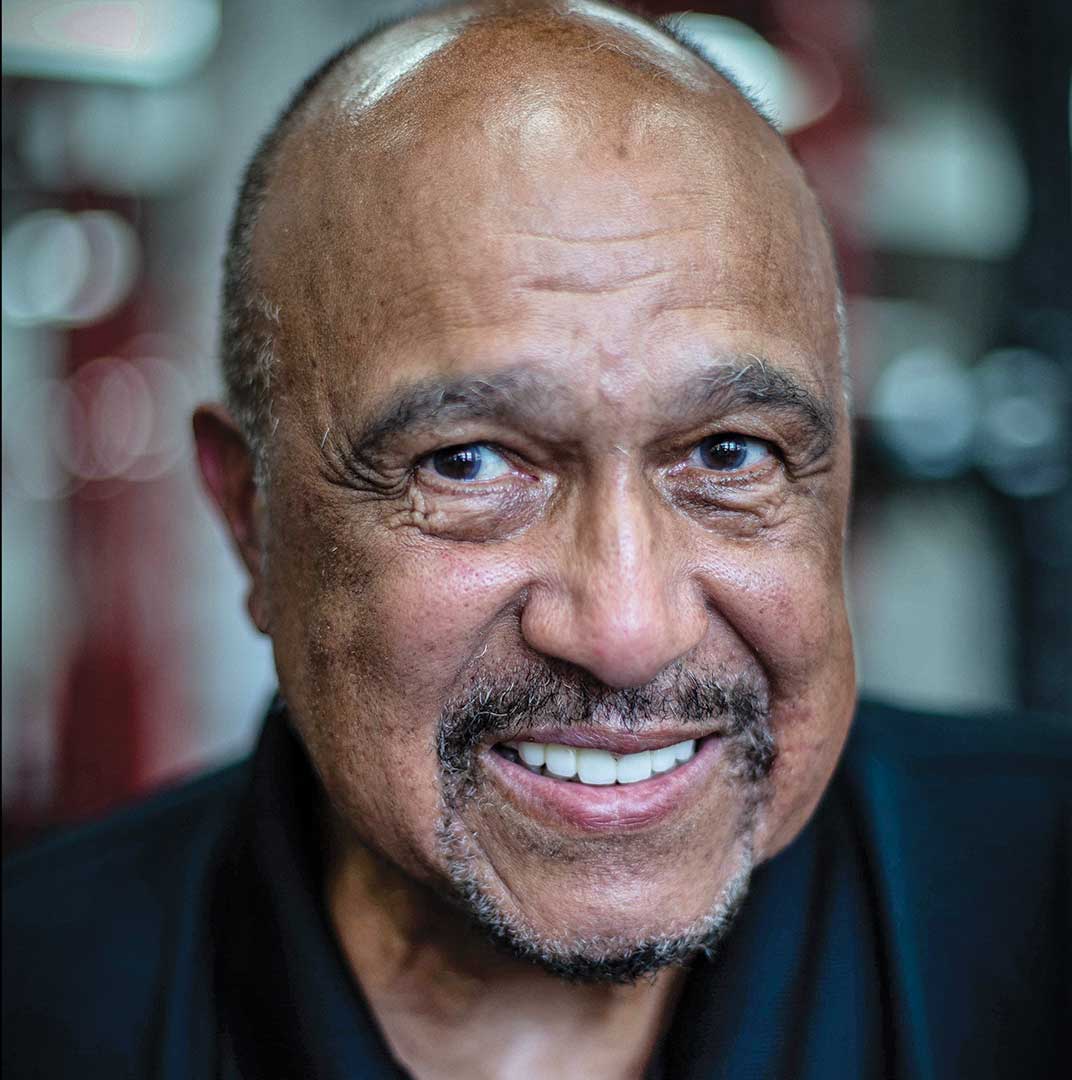

When Hill agreed to come to Maryland, it began what is now approaching a 60-year connection between Hill and the university, including seven years (2003–10) spent back at his alma mater working in the athletic department as the Director of Major Gifts, where he helped negotiate the very first naming rights agreement for the football stadium.

“To me he was one of the unsung heroes of his time because people outside of this area don’t understand that he was the first player to break the color barrier here at Maryland, the ACC and the South,” second-year Maryland coach Mike Locksley said recently.

“His story is right along the lines of what guys like Jackie Robinson did, what Tony Dungy did in winning a Super Bowl. Anytime you’re the first, there comes a lot of hard times and a lot of uncomfortable situations.”

It certainly wasn’t easy for Hill at Maryland, which had integrated the campus a decade before against the wishes of then school president Harry C. Byrd, who was better known as Curley from his days playing for and later coaching the Terrapins.

“There was an element at Maryland, especially from the Eastern Shore, that was pretty darn conservative,” said Hill, who nearing 77 owns a business in Cambridge, Md. “There was a fraternity on campus based out of Georgia, they flew the Confederate flag.”

Though he had been a groundbreaker at both Gonzaga High and Navy—and had spent his freshman year of college at Xavier University before earning an appointment to the academy—Hill said that his experience at Maryland was much different.

“Neither of those schools (Gonzaga High and Navy) said, ‘You can’t if you’re black,” Hill said. “Nobody had stepped up to it yet. At Maryland it had been ‘You can’t for a long time.'”

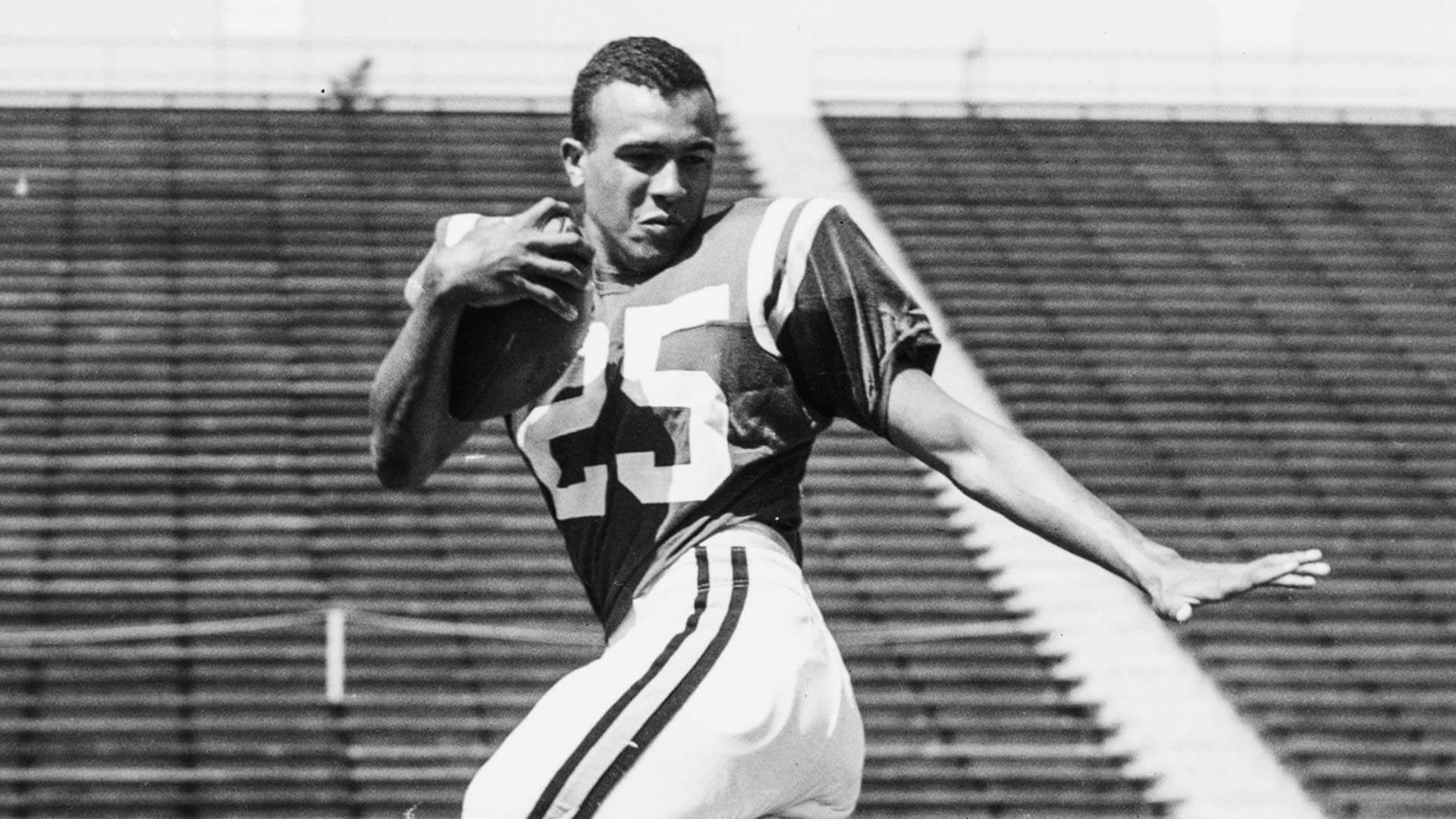

After sitting out the 1962 season because of NCAA transfer rules, Hill broke Maryland’s single-game record for receptions with 10 against Clemson, set an ACC season-record for touchdown catches with seven and threatened the school’s single-season record for receptions, finishing four shy of tying the 47 passes Tom Brown had caught the previous fall.

Hill even kicked seven PATs in eight attempts.

Though a broken foot sidelined Hill for much of his senior year, and injuries to the team’s two top quarterbacks limited his effectiveness as a wide receiver when Nugent was forced to use more of a running offense, the impact Hill made resonates to this day, not only at Maryland but throughout the landscape of college football.

It took another three years before Maryland recruited more Black athletes, with Billy Jones becoming the first to join the basketball team.

Four years after Hill came to Maryland, Cole Field House was the site of the 1966 NCAA men’s championship game when Texas Western, with an all-Black starting lineup, shocked lily-white Kentucky and changed college hoops forever. Corso said that Hill had a similar impact with college football, as other ACC schools and programs throughout the South started recruiting Black players.

“It was very, very important,” Corso said. “The thing about it is, he was as good off the field as on the field. He was a good representative. He always presented himself in a first-class fashion. And that was very important, because he was always in the spotlight with guys trying to find things wrong with him, almost as important as it was to be a football player. It was perfect.”

‘The Onlys’

‘The Onlys’

If there was anyone aside from Corso who helped Hill make the transition to College Park, it was teammate Jerry Fishman.

Fishman, a 230-pound fullback and linebacker, was a tough Jewish kid from Connecticut who found an immediate connection to Hill. The two were familiar with each other, having played twice the previous year in matchups of the Navy and Maryland freshmen.

In the first meeting, won by the Terps 27-23, Hill had scored in a 98-yard kickoff return and a 61-yard punt return while also catching a touchdown pass from a future Heisman Trophy winner and NFL legend.

Having seen what Hill had done in the first game against Navy, Fishman was ready when the Midshipmen opened the rematch with “the old Statue of Liberty play” with Navy’s quarterback Roger Staubach faking a pass and Hill taking the handoff.

This time, Fishman snuffed out the play.

“He was waiting for me, and he laid me out and helped me up and said, ‘You know what? I’m going to be your biggest nightmare this afternoon,’” Hill recalled.

When Hill showed up in College Park the following summer, Fishman was waiting again, this time with open arms.

“He said, ‘By the way, as a Jew, they don’t like me in the South any better than they like you, so we’re in the same bag,’” Hill said.

With Fishman being the lone Jewish player on the team, they dubbed themselves “The Onlys” and roomed together on the road.

“I knew what he was facing,” said Fishman, a retired attorney who now lives in Boca Raton, Fla. “He didn’t have an easy time when he came to Maryland. He had to sit out a year because he transferred and he caught hell (in practice). We were an all-white team, it was an all-white league. When he came up, there wasn’t even a Black player on the Washington Redskins.”

Fishman played a similar role with Hill — as an unofficial bodyguard — that one of Navy’s captains, 280-pound tackle Richard Fitzgerald, had in Annapolis. Fitzgerald helped Hill get through his year at the academy relatively unscathed. Fishman provided the same kind of protection at Maryland.

One day at practice, Hill was hit late out of bounds by one of his teammates, a player from Delaware who was known as a racist.

“Fishman came charging over and knocked the crap out of him,” Hill recalled with a hearty laugh. “He said, ‘Do it again, you’ve got to deal with me.’ Of all the guys I’ve played with, including the NFL, he’s arguably the toughest football player I ever encountered.”

Corso said that Fishman “behind the scenes, was the secret to Darryl’s success. I don’t know if Darryl Hill would have made it at Maryland without Jerry Fishman.”

Fishman said that the first year was particularly tough because the team’s road games were at South Carolina — where students stormed the field at halftime and again after the game trying to intimidate Hill with racial slurs and the threat of violence — as well as at Clemson and Wake Forest. The Terps played Duke in the Tobacco Bowl in Richmond, Va., the capital of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

“His first year of eligibility, he hit it the wrong possible way, all the deep South schools were away,” Fishman said. “Every game it just got worse, everyone was following you. And the worst place was Wake Forest. They had confederate flags on the lamp posts and we would tear them down and throw ‘em in the trash.”

When Demon Deacon fans started spewing racial slurs at Hill before kickoff, the team’s star and captain Brian Piccolo came over and warmly put an arm around Hill’s shoulder. In doing so, Piccolo showed the same courage and compassion as Pee Wee Reese famously displayed with Robinson.

During one road game, Hill was left woozy after one late hit.

Those attending to Hill on the field didn’t want to put an oxygen mask on his face.

“They said, ‘We’re not putting that mask on that N-word’s face,” said Fishman, who quickly came to his friend’s aid.

The trip to Death Valley

The trip to Death Valley

Perhaps the most memorable—and historically significant — experience at Maryland for Hill played out at Clemson during his junior year.

It came late in the 1963 season when the Terps traveled to play the Tigers on homecoming. Unbeknownst to both her husband and her son, Palestine Hill made plans to travel by train to South Carolina to watch her son play.

His father, Kermit, had a thriving trucking business and Saturday was typically his busiest day.

“My father had said to her, ‘Do not go to Clemson by yourself,’ and then she showed up. I was shocked,” Hill recalled.

His mother had secured a ticket despite knowing that African-Americans were not allowed to enter Memorial Stadium, relegated to an area of dirt adjacent to the stadium that some called “Ant Hill” and others had called by a racial epithet.

When a team manager told Hill that his mother had been refused entrance and was being given a difficult time from those at the gate, he told Corso he was leaving the locker room to help his mother. Kickoff was only minutes away.

“I took off my uniform and then I went out front,” he said. “She was standing there with a couple and the gentleman introduced himself, ‘I’m Dr. Robert Edwards, I’m the chancellor of Clemson University.'

“He said, ‘I’m going to take your mother with my wife and I to our booth and she can come to my house after the game and we’ll see about getting her back to D.C.’ He said, ‘You go out and play the game, and his wife, Louise, said, ‘You go out and show ‘em.’"

In a 21-6 loss to the Tigers, Hill displayed not only his pass-catching ability with 10 receptions, but also his toughness after taking several hard hits. Unlike some other teams he had faced, Hill said he didn’t have to endure any cheap shots from the Tigers.

“These kids from Clemson, they were whacking me, but they were not cheating,” Hill recalled. “They weren’t late-hitting or hitting after the whistle or gouging. They hit hard and I kept getting back up. By the third quarter, I saw the dudes in the pileup were giving me a quiet thumbs up.”

Though the Terps didn’t win, Hill’s performance was payback of sorts against legendary Clemson coach Frank Howard, who had reportedly threatened to pull the Tigers and other schools out of the ACC when Maryland signed the league’s first Black player.

Hill was not the only member of his family to make a positive impression at Clemson that day.

Palestine Hill, a Howard graduate who also earned her doctorate at Catholic before starting a long career teaching a variety of foreign languages, including Latin, in the D.C. school system, had moved the Clemson chancellor to action.

It came months after Harvey Gantt — a future mayor of Charlotte, N.C. and an unsuccessful U.S. Senate candidate famous for not getting the support of Michael Jordan in his bid to unseat Jesse Helms - became Clemson’s first African-American student.

Within days after watching the game with Hill’s mother, Edwards, himself a Clemson graduate, ordered all the “WHITES ONLY” signs to be removed from the water fountains and bathrooms on campus.

“He didn’t flinch,” Hill said. ‘He told my mother, ‘I’m just going to have the signs taken down.’ He just did it.”

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of Hill’s arrival in the ACC in 1962, both Maryland and Clemson invited him to be part of ceremonies a few weeks apart during the 2012 season. Hill said he had mixed emotions going back to Death Valley and felt uncomfortable when he walked out on the field.

Hill said he closed his eyes, as the pent-up emotions from a half-century nearly boiled over.

Then he heard a deafening roar and asked the person next to him what was going on.

“They’re giving you a standing ovation,” Hill was told.

Tags

Football