- August 18, 2020

- By Samantha Watters

A University of Maryland expert in tick-borne illnesses is leading research funded by a $3.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to create a Lyme disease vaccine based on an accepted and proven platform that might seem counterintuitive—the rabies virus.

Utpal Pal, a professor of veterinary medicine, will combine four proteins his lab previously identified as useful candidates for vaccines with the normally fearsome virus in hopes of delivering long-lasting, safe immunity from Lyme disease.

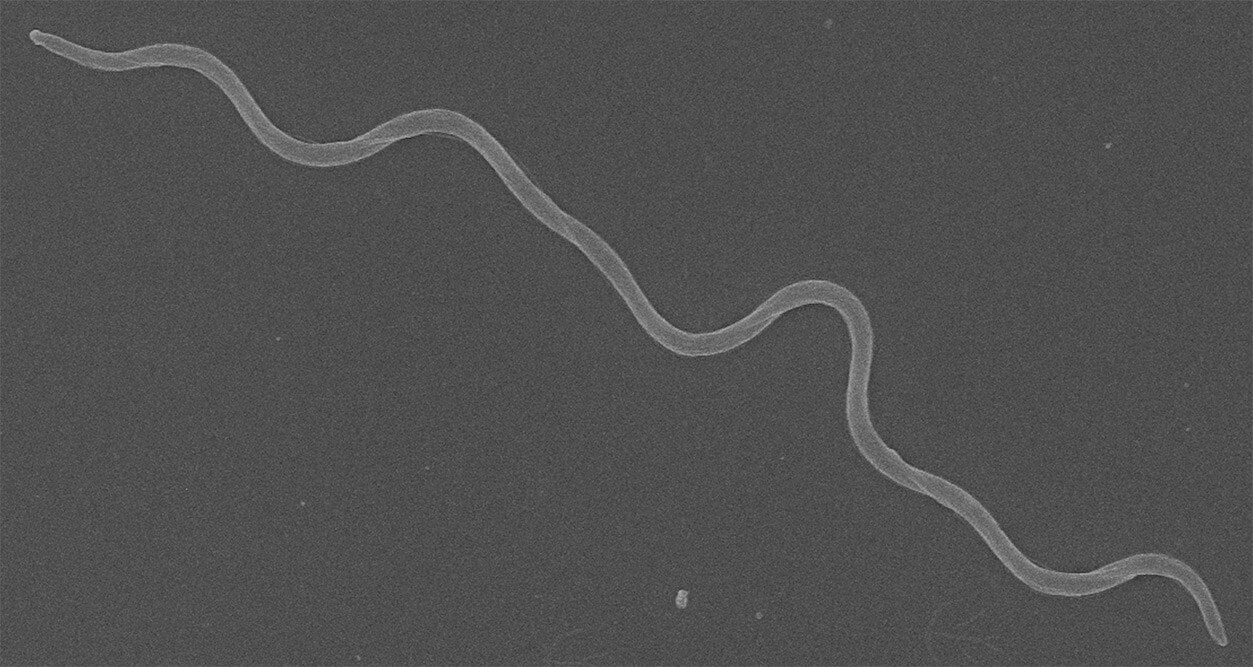

No vaccine for the disease has been available on the market for nearly 20 years, despite upwards of 300,000 new cases annually in the U.S. alone, as well as a growing burden of chronic or post-treatment Lyme disease. Infection by Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria transmitted by tick bites that is responsible for Lyme disease, can be treated with antibiotics, but it is often misdiagnosed, and a substantial fraction of antibiotic-treated Lyme patients develop neurological symptoms called post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome.

“There is no cure for that, no drug, and no treatment,” Pal said. “The only way to prevent this is to prevent Lyme, and a vaccine is a good answer for that.”

“There is no cure for that, no drug, and no treatment,” Pal said. “The only way to prevent this is to prevent Lyme, and a vaccine is a good answer for that.”

The approach being explored by Pal and partners at the Thomas Jefferson University’s Jefferson Vaccine Center—known for its work with the rabies virus as a platform for vaccines—has proven effective for other viral vaccinations.

They’ll be testing the four proteins with three major types of rabies vaccine platforms that are potentially effective for Lyme disease: The first uses an “attenuated” virus, in which the virus remains whole and viable, but is incapable of producing full-blown infection. More popular for safety and efficacy reasons, as well as the platform for the actual rabies vaccine, is a platform using a whole, but inactivated (or dead) virus. A third uses a protein or a piece of a virus to produce a “virus-like particle,” or VLP.

“In this case, you create a sort of shell of a virus that looks like the virus and has viral proteins on the outside but no actual virus on the inside, so the body is tricked into developing defenses against the virus itself,” Pal said.

Pal is also looking at stopping Borrelia infection from two angles, targeting both the pathogen’s proteins and the tick proteins that help keep the bacteria alive and ensure it can be transferred to humans. In essence, it’s like trying to dismantle the train—Borrelia—as well as the tracks—the delivery mechanism from ticks to humans—all at once, which has never been done before, said Pal.

Once Pal and his team identify the best combination of vaccine platform and protein antigens, they will test this option in mice to examine the underlying protection mechanisms of the vaccine and determine its overall effectiveness—and perhaps find other uses as well.

“If we can produce something effective for Lyme disease, we can help with this problem and also understand how we can apply it to other tick-borne diseases,” he said.

Topics

Research