- July 08, 2019

- By Annie Krakower

Years ago, Richard Bell sat on the tarmac at Dulles International Airport, dismayed that his delayed flight grounded his chance to see a then-new musical in New York about the “10-dollar founding father,” Alexander Hamilton.

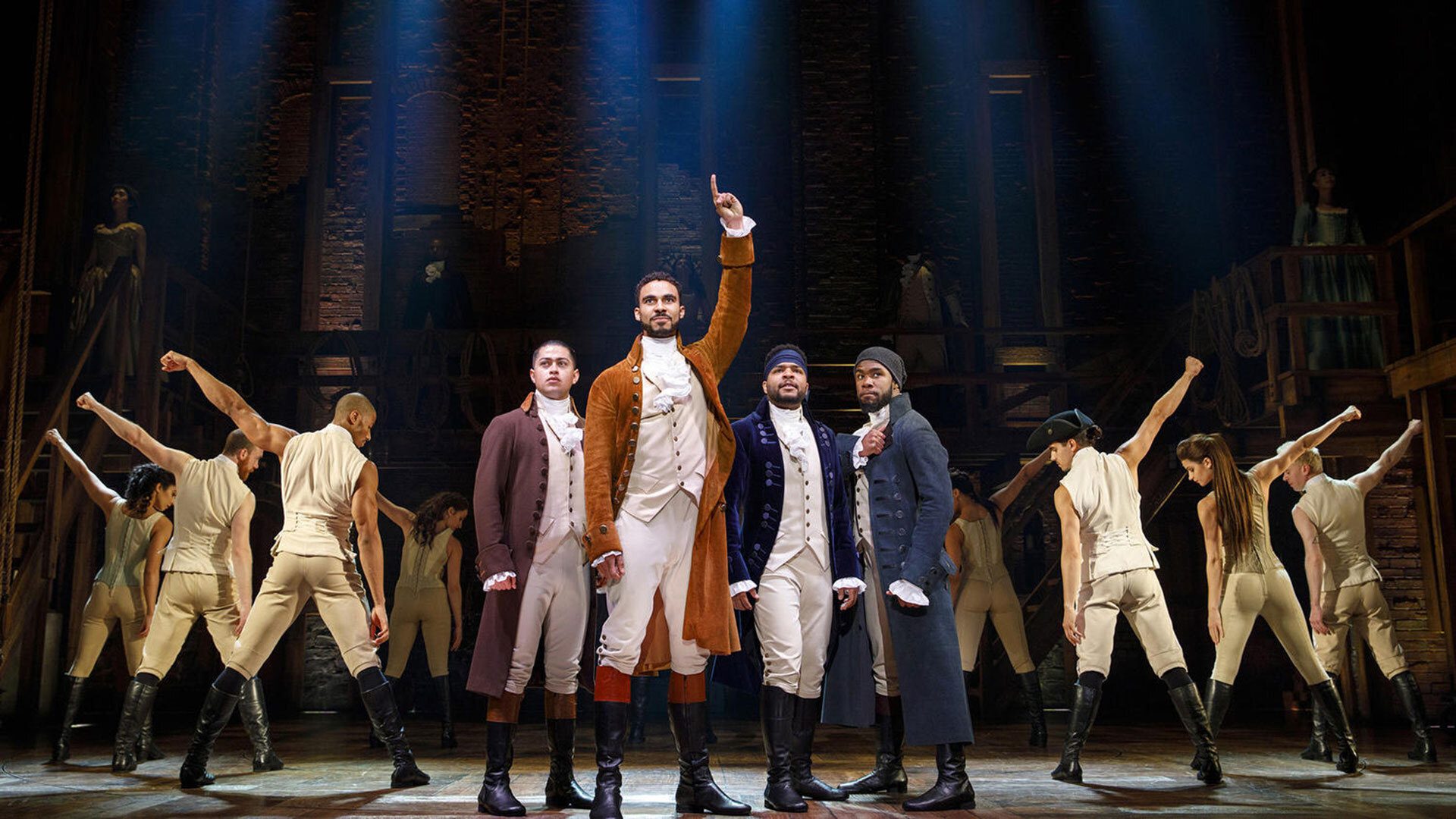

Many fans can relate to missing out on “Hamilton: An American Musical,” though Lin-Manuel Miranda’s smash hit has expanded to venues beyond Broadway—including at Baltimore’s Hippodrome Theatre until July 21.

Bell, an associate professor of history, later saw “Hamilton” in Cleveland, Chicago, Louisville and even his native London, and now he teaches about the periods the show covers in his classes at UMD. While he’s a fan, he’s also analyzed the musical through a scholar’s lens, giving lectures at museums and to historical societies around the nation. He spoke with Maryland Today about what he admires about the show and answers the question: Does it measure up to revolutionary reality?

How did you first get into “Hamilton”?

I'm a longtime fan of musical theater. I've seen “Cats” seven times—I don’t recommend that to anyone now, but it was a mainstay of my teenage years. “Hamilton” is a great piece of musical theater. It’s got characters you care about, it’s relentlessly propulsive and dramatic, and some of the songs are just luminous.

And then, of course, I’m a historian. I study the American past, particularly the period between the American Revolution and the Civil War. So to see some of the events, people, themes, questions and ideas that I teach up on stage being sung about, being sometimes rapped about, was extraordinarily interesting.

Historically, what does the musical get right?

Quite a lot, actually. It captures all sorts of complicated truths about the American past, like the importance of the French alliance during the war, George Washington’s struggle to find good lieutenants and the bitter nastiness of partisan politics after George Washington retires.

It tells us why sensible, intelligent men dueled with each other and how presidential elections worked before the passage of the 12th Amendment, which put an end to the practice of the runner-up becoming vice president. If you didn’t know anything about any of this stuff before you saw this show, you could do worse than use “Hamilton” as your textbook.

What does it get wrong, and does that matter?

To be fair, if your job is to turn an 800-page biography of the first secretary of the treasury into three hours of all-singing, all-dancing Broadway fun, it’s perfectly understandable if you occasionally condense characters, collapse time and move a few things around.

But the larger answer is that when it comes to larger themes, like the depiction of the American Revolution, 18th century women, the role of immigrants and questions related to slavery and race, this show falls a little bit short. I’m a British person with a British accent, so you should take what I say with a grain of salt, but all historians who study the American Revolution have critiqued the show for its fairly simplistic depiction of the American Revolution as a struggle between patriot heroes and their not-so-heroic opponents.

It’s easy to say that we shouldn’t take Broadway theater too seriously. Certainly no one goes to see “SpongeBob SquarePants: The Musical” expecting SpongeBob, Squidward and the boys to get marine biology just perfectly right. But with “Hamilton’s” extraordinary success and because of the explicit attempts Miranda has made to imbue it with historical credibility, we must take it seriously. We must ask ourselves, “Is this good public history?” The answer to that question matters, of course, because by now an awful lot of people have seen this show.

What’s the impact of having the key roles played by performers of color?

Because the stage is full of non-white actors, audiences don't seem to notice that there are no black characters up on stage. I think the show would be richer if some of the scenes contained enslaved characters and free black characters. We know they were hugely important to the story of the American Revolution.

Miranda sees this very differently. He has said that the casting of non-white actors in the roles of white founding fathers, many of whom were slaveholders, is intentional, political and progressive, a way to highlight the hypocrisy. I’m not sure who’s right.

What does the show’s rap style add to the story?

The use of rap and hip-hop to tell the story of the American Revolution is the smartest and best decision Miranda made, because these are the musical styles associated with the streets, with defiance and ambition, with a put-upon people ready to rise up.

Why do you think “Hamilton” has become so popular—and is it worth the hype?

Politically, it’s worked hard to offer something to everyone. When the patriot characters talk about what they’re fighting for, it’s intentionally pretty vague. They’re fighting for freedom, but freedom from what, freedom to do what? It’s left hazy enough that audiences can project whatever agenda they wish onto the patriot characters and come away happy.

To be clear, I love this show, and if it’s starting conversations about what really happened and about the larger themes and questions produced by the American Revolution, that’s a wonderful thing. Hamilton has provided scholars like me with the ultimate teachable moment.

Writer Annie Dankelson has seen “Hamilton” in New York three times—two of which were the result of winning a $10 ticket lottery.

Topics

Arts & CultureTags

History