- March 17, 2015

- By Chris Carroll

Hong Kong, New York City and Ferguson, Mo., are just three of the places where crowds took to the streets in the past year to demand freedom, decry police violence and push for environmental protections.

While the messages of the protests are clear, it’s a little less obvious what drew the masses to show up in the first place—the influence of their friends, the websites they read, the unions they belong to? What was the role of social media? And crucially, how does protest participation carry over into broader activism?

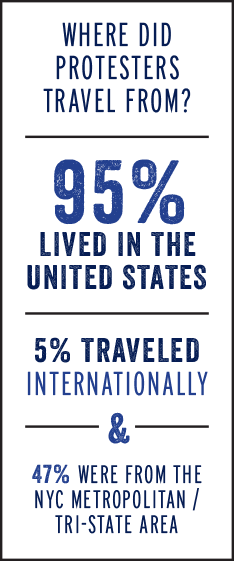

Those unanswered questions motivated Dana R. Fisher, professor of sociology, as she and a small army of assistants fanned out into the crowd—estimated as large as 450,000—at the People’s Climate March last September in New York City.

By the end of the day, Fisher and her research team had convinced 468 randomly selected protesters to fill out a survey delving into how and why they’d come to the largest-ever climate demonstration.

Fisher’s study was the subject of a recent short film, “The Collectors: Political Action,” part of a series about data gatherers by ESPN Films and FiveThirtyEight.com. The film brought wider attention to Fisher’s study of protests, an effort she says she’s pursued as a “labor of love” since 2000.

Fisher’s preliminary research results are in, and somewhat unsurprisingly, she says, climate march participants overwhelmingly identified themselves as liberals with university degrees. They also tended to be women.

Fisher’s preliminary research results are in, and somewhat unsurprisingly, she says, climate march participants overwhelmingly identified themselves as liberals with university degrees. They also tended to be women.

More interesting, she says, are the results that show how people learned about the Sept. 21 march.

“About half the respondents learned about the protest from someone they knew… but at the same time there were a lot of people who came out who had no previous protest experience and who found out about it through non-relational channels” such as advertising posters, Fisher says.

Social media played a significant role in mobilizing over 20 percent of protesters, but researchers need better methods to understand webs of online relationships, she says.

“If I learned about this through Twitter, for instance, is it because I followed my sister, or because I followed (environmentalist and march organizer) Bill McKibben?” she says.

It’s not simply an abstract, academic distinction.

“Organizers tend to think people are going to come out and participate in a party in the street with friends or people they know, or people they’re affiliated with through an organization or business,” Fisher says. “If instead you get a bunch of people who don’t know each other but follow each other on Twitter, that will significantly change the quality of interaction at a protest.”

Jamie Schutz, who directed the short film, said his biggest surprise of the day was the number of people who’d arrived solo, drawn by the Internet and social media. He realized after seeing Fisher at work that most of media reports he’s ever seen about protests only scratched the surface.

“They’re stories about generalities, and you don’t get an understanding of who is there and really why they’re at the protest,” he said. “Dana goes much deeper.”

Fisher’s digging on the subject has resulted in broad-ranging contributions to the study of activism and social movements, says Michael T. Heaney, an assistant professor of organizational studies and political science at the University of Michigan who has collaborated with Fisher on research.

Fisher’s digging on the subject has resulted in broad-ranging contributions to the study of activism and social movements, says Michael T. Heaney, an assistant professor of organizational studies and political science at the University of Michigan who has collaborated with Fisher on research.

“In particular, her work helps to demonstrate the critical role that organizations play both in facilitating and, at times, undermining grassroots mobilization,” Heaney says.

Leaders of social movements tend to think of protests as gateways for people to become more involved in a variety of activities to promote change, Fisher said. But if they don’t find ways to make sure people connect at the events, their movements could suffer.

The biggest realization Fisher says she’s had in 15 years of protest research is that marches and demonstrations are only a beginning. Social change requires a suite of political tactics to work.

“You can’t just go into the streets for one Sunday and expect for the world to change,” she said. “If you look at the civil rights movement in the United States… it wasn’t just marching on Washington. It was boycotts and voter registration drives and a whole bunch of complementary efforts to effect change.”

Tags

Research