- February 24, 2022

- By Shannon Clark M.Jour. ’22

The sweetness and light of fermented honey blend with crisp flavors of Frederick County-grown apples or richly sweet grapes, evoking notes of cinnamon or honeysuckle … well, that sounds intriguing. But what is it, you might be asking?

In a country where wine frequently means well-structured (i.e. pricey) French vintages or fruity blasts from California or Australia, it’s a fair question. The answer: a different kind of wine entirely, known as mead. After a heyday hundreds (or thousands) of years ago and being relegated more recently to renaissance fairs, it’s now “on the rise,” according to Vogue.

It’s never really fallen from favor, however, in Eastern Europe, where the Loew family began crafting it more than 150 years ago, a tradition it continues today at Loew Vineyards in Mt. Airy, Md.

Rachel Loew-Lipman ‘15, winemaker and vineyard manager, is working to uphold the Loew legacy and share her family’s story through every glass of mead (or grape-based vintage) that’s poured.

“I want to reconnect people to a beautiful but lost history,” said Loew-Lipman, who graduated with degrees in plant science, horticulture and crop production and in communication.

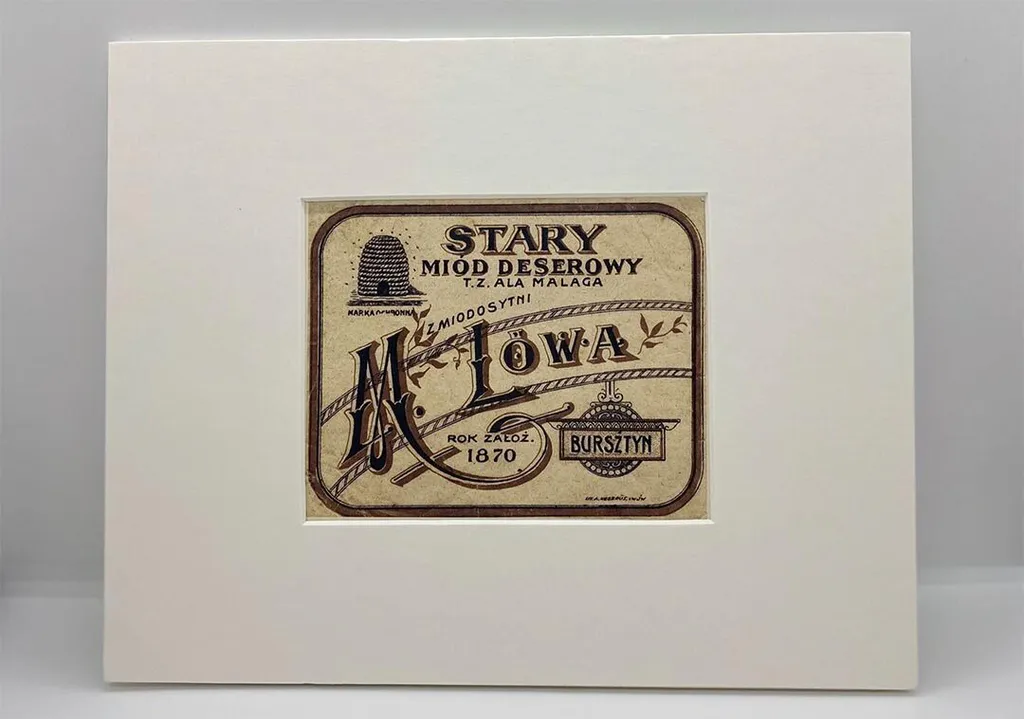

The history that she's been piecing together from family memorabilia, handed-down stories and old press clippings begins with a family patriarch. In 1870, Meilech Loew started what the family believes was the first meadery to ship its products internationally, founded in what’s now western Ukraine, then a part of divided Poland ruled by Austria-Hungary. His son Eisig established a well-known meadery in Lviv, Ukraine (then known as Lwów by its primarily Polish-speaking residents).

The Loews’ mead-making continued as the tides of war and changing national boundaries swept repeatedly over the region—until World War II, when the business collapsed amid the Holocaust. Most of the city’s large Jewish population of some 200,000 residents, which included the Loew family, was murdered. Meilech’s grandson Wolfgang survived as a member of an underground group, and then endured a series of concentration camps before leaving Europe for the United States. Once here, he changed his name to William, went to night school to earn a degree in electrical engineering, and started a family.

Years later, ready to retire from a job as a regulatory expert at the FDA, Loew took the plunge and re-established his family’s ancestral business, founding what’s now one of Maryland’s oldest wineries. In 1986, with the help of his wife, Lois, and Philip Wagner, known at the time as the “father” of the American grape industry, he produced Loew Vineyards’ first batches of wine.

Almost 40 years later, the tradition burns strong in Loew-Lipman.

“I spent a lot of time on the vineyard. I’ve always loved it and I worked part-time for my grandfather while I was in college,” she said.

As the only full-time employee, Loew-Lipman is using the knowledge she gained as a plant science and communication major at the University of Maryland to manage the daily operations of the vineyard. Each day looks a bit different. In the harvest, Loew- Lipman can be found at the vineyard from sunup to sundown, tending vines or harvesting grapes for the wine.

She oversees the creation of signature beverages, starting with the heating of honey and water; once it cools, she pitches yeast into the mix, and apple juice (creating a mead known as cyser) or grape juice (resulting in one called pyment) are added. The ingredients ferment in a cool place until they’re ready—a minimum of four weeks, and then are barrel-aged for nearly a year.

Loew-Lipman hasn't confined her work–or learning–to her own family’s vineyard. With the help of Chris Walsh, a professor in plant science and landscape architecture, she spent a summer in France working at a local vineyard and learning how to better her craft by incorporating new perspectives from perhaps the world’s most-respected winemaking country.

“I encouraged Rachel to get outside of working with just her family and to travel,” said Walsh. “She spent the summer in France working in a winery, and after her study abroad ended, she stayed another five weeks to work alongside her mentor. Her passion always stood out to me.”

During the winter, when there’s little winemaking to be done, there’s still marketing, and Loew-Lipman has been focusing on the vineyard’s Wine Club, which sends subscribers three different wines each quarter, along with other perks. As mead rises in popularity and people focus on the comforts of hearth and home during the pandemic, sales have been taking off.

“The growth we have seen in our business in just a year is incredible, and I want to continue to share my family’s story as we grow,” she said.

The story and the wines blend like the flavors of mead; one of them, “Thirteen, Honey & Grape” is a nod to founder Bill Loew (still involved with the business in his mid-90s) and his experiences surviving the Holocaust and later reviving the mead-making tradition. While held in a concentration camp, he was tattooed with six numbers that added up to 13—now the family’s lucky number.