- August 12, 2016

- By Chris Carroll

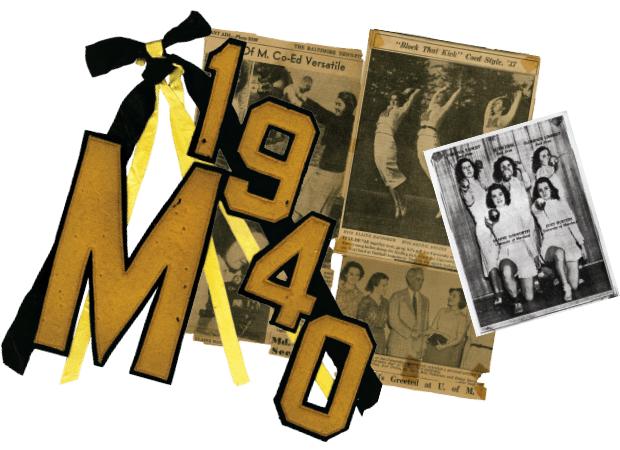

She was a cheerleader, an athlete, a sorority vice president with a handsome boyfriend and a lofty GPA. Elaine Danforth ’40 was also bored.

She was a cheerleader, an athlete, a sorority vice president with a handsome boyfriend and a lofty GPA. Elaine Danforth ’40 was also bored.

Then, in her senior year, she saw an ad in The Diamondback seeking volunteers for the U.S. government’s new Civilian Pilot Training Program. “That was the first thing I had seen that really interested me,” she recalled in an interview decades later.

Underage and certain her mother would never approve, she got her father’s permission for flying lessons at College Park Airport. The pilot’s license she received after months of training opened the door to greater adventure in 1944 when the now-married Elaine Harmon entered the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), the first group of American women to fly military missions.

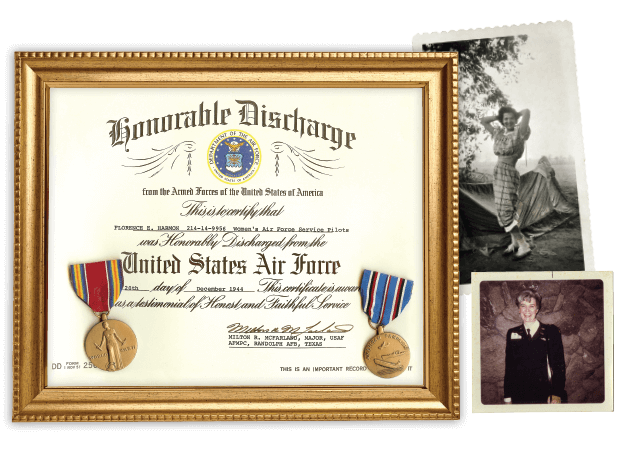

The organization was unceremoniously disbanded later that year and the jobs taken over by men before the women could be sworn into the military, as originally planned. Nevertheless, she and others fought for and won recognition from Congress of the WASPs as war veterans in 1977.

Harmon, 95, died last April planning her final act as a WASP—inurnment of her ashes at Arlington National Cemetery, where the remains of fewer than 20 of her old colleagues have been placed.

Today, however, Harmon’s ashes remain tucked away in her daughter’s closet in Silver Spring, Md. Thanks to a new reading of the 1977 law by the Army, the gates of the nation’s most hallowed cemetery were closed to WASPs a month before she died.

“I’m glad my mother never learned about this,” Terry Harmon says. “She had fought so hard for the WASPs over the years. It’s a matter of honoring and preserving their legacy, not so much having her own place there.”

In denying her a place, the Army resurrected questions about who deserves a resting place at Arlington and what it meant to serve decades ago when strict gender roles severely limited women’s options. (By contrast, the Pentagon last year opened all military occupations to women.) Army officials have pointed out that the 624-acre cemetery overlooking the Potomac River is short on space, but WASP supporters question how the urns of a few more WASPs could be a burden.

Harmon’s family has pushed to overturn the decision, backed by widespread media coverage and a petition on change.org that had gathered 175,000 signatures by mid-April.The pressure appears to have worked. Bills to overturn the decision introduced by a bipartisan groups of women legislators in the House of Representatives and the Senate unanimously passed both houses this spring, and President Barrack Obama is expected to soon sign the legislation into law.

“If they were good enough to fly for our country, risk their lives and earn the Congressional Gold Medal,” said U.S. Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.), a sponsor of the bill, “they should be good enough to be laid to rest at Arlington Cemetery.”

Whether they’d actually be good enough was an open question when the Women Airforce Service Pilots organization was born in 1942 to help fill a demand for pilots as the war intensified across Europe and the Pacific.

Army Air Forces brass decided the thousands of female aviators in the United States could ferry planes stateside from factories to ports, help with pilot training and even tow the airborne targets for anti-aircraft gunners in training. The women who joined were told they would eventually be commissioned as military officers.

“They saw it as an experiment—can women do this?” says Kate Landdeck, an associate professor of history at Texas Woman’s University who has studied the WASPs throughout her career and knew Harmon well. “And when they realized, ‘Oh, they can,’ then it was, ‘Well, let’s see what else they can do.’”

It quickly became clear that WASPs were more than a novelty. They could be relied on to deliver planes cross country faster than many men “because they didn’t have their little black books with them,” Harmon laughingly told an interviewer with the Women Veterans History Project in 2006.

When some male pilots balked at flying the new B-29 bomber after frequent engine fires, Paul Tibbets, an officer overseeing its development (and eventual pilot of the Enola Gay, which dropped the first atomic bomb) turned the plane over to the WASPs.

“While they were being trained, they had a fire in the engine, and they handled it, no problem,” Harmon said. “So the men eventually decided, you know, if women can do it, we can, too.”

Nearly 1,100 eventually earned their wings, collectively flying 77 kinds of airplanes 60 million miles during World War II, Landdeck says. They frequently did the same jobs as male military pilots but were paid nearly 20 percent less and got none of the insurance or benefits granted to their male counterparts. They saw no combat, but 38 WASPs died while flying. Their families, not the military, bore the cost of bringing their bodies home for burial.

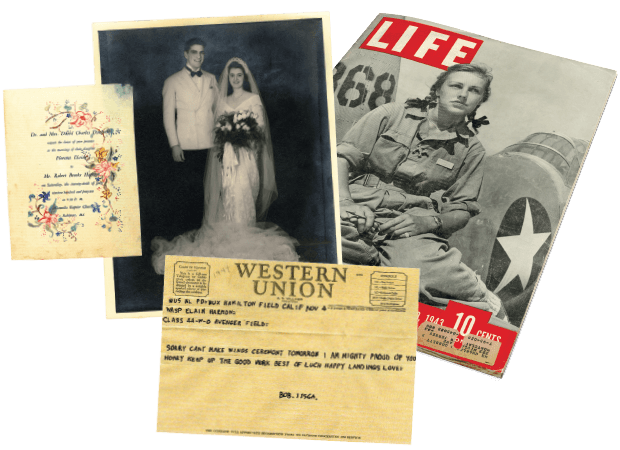

Elaine Harmon learned of the WASPs in a 1943 Life magazine article, and ached to sign up. She’d graduated from UMD with a degree in microbiology, one of the few degree fields she said were open to women beyond teaching and nursing. But the lab jobs she’d held were dull.

“I never really knew what I wanted to do,” she said in a 2006 interview with the Women Veterans Historical Project, joking, “I’m still trying to figure out what I would like to have as a career.”

At first, the 35 hours of flying time from her lessons while enrolled at UMD were too few to qualify for WASP training, but Army officials later eased stringent entrance requirements.

Her husband, Robert Harmon, was repairing military aircraft in the Pacific at the time. His father had been a prominent World War I pilot, and a brother was a bomber pilot, but a heart defect kept Robert out of the military. He urged his 24-year-old wife to follow her own heart and join.

Her mother was another story. Convinced the program was not only dangerous but the province of “loose women,” she opposed her pilot lessons from the start and refused to correspond with her daughter throughout the time she served.

Elaine Harmon reported for training in March 1944 at Avenger Field near Sweetwater, Texas. Half of each day was spent in ground school on subjects like meteorology and the principles of navigation. The other half was spent learning to fly military planes.

She was initially put off by the brash attitudes of many of the young women she encountered. “I’m not going to like these women,” she recalled thinking. “They’re so confident and full of themselves.”

But the training class soon bonded in the way only military units can. On a training run over Munday, a small Texas town that was home to a class member with whom she’d become close friends, she engaged in her only instance of “Top Gun”-style hotdogging. She decided to fly low and give the residents a wakeup call.

“I got to buzzing, and I thought, oh, this is great fun,” she said. “I kept buzzing and buzzing, and I looked over, and there was an instructor.”

She returned sheepishly to base, worried she’d be expelled. The only problem was, the instructor who’d spotted her antics didn’t know who was flying the plane—only that it was a member of a training group where everyone’s name began with an H. When he confronted the instructor in charge of her own group, Harmon’s squeaky-clean reputation saved her. “It could have been House, Hershey or Hughes, but it could never have been Harmon,” her instructor said. Unsure who to blame, they dropped the matter.

WASPs lived under the code of martial discipline, marching in formation, making their beds tight enough to bounce a quarter, and submitting to inspection.

“It was strictly military.” Harmon said in 2006. “We went to bed at night with taps, and we got up in the morning with reveille.”

Their civilian status caused some deviations from military norms. For instance, women who failed the training were responsible for paying their own way home, so the others passed a hat to help with train tickets. They had no regular training uniforms or laundry service, either. After a hard day in the Texas heat, caked with sweat and dust, they trudged into the shower wearing their flight suits—made for men and often comically oversized—to spray off the grime.

Harmon finished training in November 1944 and reported to Las Vegas Army Air Field, where her main job was to ferry male pilots into the air whose view of the outside world was obscured so they could practice instrument flying. Interactions with airmen were professional, with no hazing or abuse, Harmon said. Nevertheless, the work she and other WASPs often did was the kind male pilots considered beneath them.

But the WASPs, aware they were doing something quietly revolutionary, were far less jaded than the men. They relished what flying time they could get, and many hoped for long-term military careers, says another WASP, Bernice “Bee” Falk Haydu of Florida.

“Where else could I go and fly these big, wonderful airplanes?” she says.

But forces in Washington had already dashed those hopes by the time Harmon reached Las Vegas.

Army Air Forces commander Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold had long supported including women in what would soon become a separate service branch, the U.S. Air Force. But as enemy air forces crumbled, the need for pilots shrank, says Landdeck of Texas Woman’s University.

Male civilian pilot instructors were losing their draft-deferred jobs as a result, and facing the prospect of being sent into combat. They wanted WASP jobs, and they took their concerns to receptive legislators on Capitol Hill, she says.

Harmon particularly remembered misogynistic attacks from influential newspaper columnist Drew Pearson. “He wrote these articles about us where he would make statements like, ‘These are million-dollar glamour girls wasting the taxpayers’ money,’” she said in 2006. “He never bothered to investigate what we had done.”

Congress rejected Arnold’s proposal to militarize the WASP program, which was ordered to disband by Dec. 20 with none of the ceremony that typically accompanies the dissolution of a military unit. Harmon was able to catch a military flight, and then took a train home to Baltimore, where it was as if she’d never flown for the military at all.

Many years later, former WASPs around the country were surprised by news stories in 1975 announcing women would be admitted to the Air Force Academy. For the first time, journalists intoned, American women would fly military planes.

It’s like we’d never existed, Harmon realized.

She’d spent three decades raising four children in Colesville, Md., both with her husband and after he died in 1965, but she still had a military pilot’s spunk and tenacity. The reports spurred her and others to action.

“We started trying to find each other,” she said. “I got in touch with a few I knew, and they knew some others, and everybody was doing this all over the country.”

Harmon and other WASPs had long rued obeying the Army’s order not to cause a fuss when the organization was disbanded in 1944. Now they were determined to get the recognition—as well as important benefits like Veterans Administration health care—that had been denied them.

The effort was assisted by Washington lobbyist Bruce Arnold, Gen. Hap Arnold’s son, and Sen. Barry Goldwater (R-Ariz.), who’d flown with WASPs. Harmon, treasurer for the campaign, believed the tipping point might have come when a group of them showed House Speaker Tip O’Neill an album with one of the honorable discharge certificates they’d all received.

“He said, ‘That’s just like mine. These women are veterans,’” Harmon recalled.

With veteran status attained in 1977, Harmon spent her later years speaking to journalists, schoolchildren and historical researchers, making sure no one ever forgot about the WASPs again. And her taste for excitement never flagged: She went bungee jumping in her late 70s and celebrated her 87th birthday with a ride in the kind of trainer she’d flown in the 1940s.

Elaine Harmon died in April 2015 after a long battle with breast cancer. Terry Harmon had already begun planning her mother’s Arlington funeral when she learned that outgoing Army Secretary John McHugh had concluded that the law granting WASPs veteran status qualifies them for Department of Veterans Affairs-run cemeteries, but not the Army-administered Arlington.

For families and surviving WASPs, it was the latest display of systemic disrespect. Most, like Bee Haydu, always planned to be buried near home. But some, like Harmon, wanted to act on their belief that WASPs should be represented in Arlington.

“They lived under military orders, they fought, they lost their lives—they were military in everything but name,” Haydu says. “And they deserve to be honored and remembered like other veterans.”

McHugh’s move sparked a backlash online and on Capitol Hill. Rep. Martha McSally (R-Ariz.), a retired Air Force colonel who was the first American woman fighter pilot to fly in combat, took up the cause and drove the legislation that now looks certain to reverse the decision. Even the Army appears to be on board, with acting Army Secretary Patrick Murphy recently backing the legislation before Congress.

After a year’s delay, Terry Harmon is again planning a funeral.

“It was my mother’s wish to be placed in Arlington, but also her wish that we not make a big fuss over her,” her daughter says. “We had to put one of those wishes aside to make sure the legacy of the WASPs was honored. But I think she’d be incredibly proud her children and grandchildren took this up for her and for all of them.” TERP

This story has been updated to reflect the U.S. Senate’s May 10 passage of a bill to authorize WASP inurnments at Arlington.

Materials Courtesy of the Harmon Family