- May 12, 2020

- By Chris Carroll

First, a message of reassurance from University of Maryland Extension specialist and entomology Professor Emeritus Michael J. Raupp: That’s probably not a “murder hornet” buzzing around your porch and adding to your stuck-at-home stress.

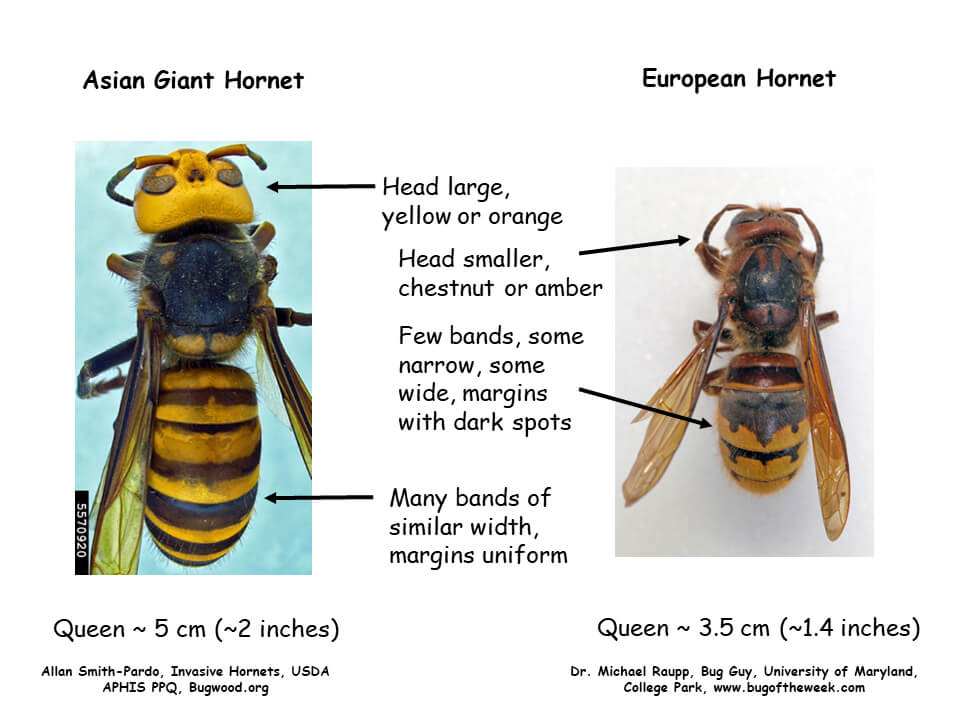

Since a New York Times story last week spawned interest—and horrified reactions—nationwide, Raupp said he's been "totally swamped with people sending me images of wasps they’ve found in their houses, but they’re all turning out to be something we call the European hornet, which is very docile. You’d probably have to grab it to get it to sting.”

Although amateur bug watchers can learn to tell the difference, it isn’t irrational to be a bit on edge about these invasive pests, recently found in isolated colonies in the Pacific Northwest. Asian giant hornets, as entomologists commonly call them, grow to nearly two inches long—big enough for a few stings to be hazardous even if you aren’t allergic. And their three-part strategy to destroy already-struggling bee colonies, which are crucial for agriculture, calls to mind an insect-world “Game of Thrones.”

Raupp, aka “The Bug Guy” in his frequent media appearances, said there is some good news: While the species seems threatening, the murder hornet hasn’t taken over the country by a long shot—we just need to take steps to ensure that remains the case.

How soon could we expect Asian giant hornets to spread from the Pacific Northwest to here?

Left on their own without human assistance, the range for these guys is a matter of kilometers per year—certainly not tens of miles or anything close to that. So given their own natural biology, even with no intervention, it could take decades to become widely distributed throughout the United States.

So we’re in the clear?

Here’s the problematic piece. The colonies discovered in the Pacific Northwest were genetically distinct, suggesting multiple introductions from overseas. So in theory, a ship could leave a port in Asia and sail across the Pacific, through the canal and up to the port of Baltimore or Norfolk, open up a container, and a single impregnated female could establish a new colony here. We’re in a global economy, with an increasingly global biota, and with human transport, species can move very rapidly. However, we know from many studies that the likelihood for an exotic species to find a means of transit from its native home to a new one, survive a journey from afar across an ocean, arrive in a new land, best predators and the environment in the new land, and survive to reproduce, establish a breeding population and become a pest is very, very small.

“Murder hornets”—that’s a drastic nickname. Is it really warranted?

It definitely sells newspapers. Is it an entomological term? Absolutely not. The term comes from a very unusual behavior they have. The hunting strategy of most hornets is to go out and find prey individually. They’ll find a caterpillar, they’ll chew it into a ball—a meatball, basically—and bring it back to the colony to feed the young. These hornets, however, have a three-phase attack and specialize on honeybees, which makes it super-duper problematic.

How so?

The first phase is just hunting individuals like other hornets. But in the autumn, they switch to a different hunting behavior and focus an attack on a single hive. As honeybees come out to defend it, the Asian hornets capture them, decapitate them and throw them on the ground in front of the hive. It’s called the “slaughter phase,” which led to the nickname. In the third phase, the “occupation phase,” they move into the hive and post guards outside to attack any animals, other hornets or beekeepers who approach. Inside, they’re pillaging and pulling larvae out of their cells to take back and feed their own babies. A study found that 30 hornets resulted in the death of about 25,000 honeybees in a matter of hours.

Are they a threat to people?

Oh yeah. Even the though the venom is only about half as toxic as a honeybee’s venom, the extraordinarily large size of these hornets results in delivery of a far, far greater volume of venom.

What are the general marching orders to contain this species?

The key element now—and this has a very strong analogy to our current situation with COVID—is boots on the ground, eyes on the field. The folks at the Washington State Department of Agriculture are doing a great job right now with their response. It involves setting up trapping devices, and a citizen science project to help people locate and identify these wasps. There’s also an effort to let beekeepers know what to look out for. If they’re found, a response team will go out and destroy these colonies

More broadly, there has to be a change. We have seen the problem over and over again—the emerald ash borer killing millions of trees, the brown marmorated stink bug despoiling crops and getting into our houses. In my opinion, what this calls for is tightening up regulations on things like how many shipping containers are inspected either before they leave the port or after they arrive to try to eliminate the entry of invasive species into our country.