- May 16, 2017

- By Liam Farrell

After conquering the city of Łódź, the Nazis decided to destroy its past and its future. German forces renamed the Polish textiles and manufacturing center “Litzmannstadt” following their September 1939 invasion, with streets and squares given honorariums for Adolf Hitler, Hermann Göring and Otto von Bismarck. As ethnic Germans were imported to remake the city’s population, Nazis herded more than 100,000 Jews into a ghetto. Between January and May 1942, tens of thousands were murdered in the poison gas vans of the Chełmno death camp.

Four months later, on a bright and hot Sept. 4, Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the Nazi-appointed head of the Jewish elders, stood before an anxious crowd and confirmed the terrifying rumors: The Nazis planned to deport anyone under 10 or over 65 years old.

Consumed by fear over what the occupiers would do if their orders weren’t followed, Rumkowski urged compliance.

“They are asking us to give up the best we possess—the children and the elderly,” he said. “Brothers and sisters: Hand them over to me! Fathers and mothers: Give me your children!”

Over the next week, nearly 16,000 people were taken to their deaths, with another 600 fatally shot. Yet at this particular hellish moment, the faith that Rumkowski and others had at the ghetto’s outset—that the valuable Łódź industry provided by Jews would ensure survival—was not entirely misplaced. Reliant on the city for everything from pillows and mattresses to military uniform repairs, the Germans exempted 2,500 relatives and children of administrators and workers from the “resettlement” to Chełmno.

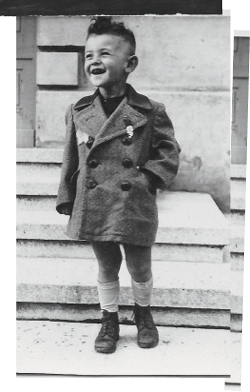

On the sixth page of the type-written “Namentliche Liste der von der Aussiedlung befreiten Personen nach laufender Nummern”—roughly, “List of Names of the Persons Exempt from the Resettlement According to Serial Number”—with an incorrect birth year and missing letter in his first name, was No. 178, Włodzimierz Kruglanski, the 3-year-old son of a shoe production manager.

Today, Arie W. Kruglanski is a 78-year-old psychology professor at the University of Maryland. Pulled out of the 20th century’s darkest abyss by his family’s hard work, ingenuity and luck, Kruglanski has spent his career studying how people make decisions—and why a portion become extremists bent on using violence.

As scholars and experts around the world debate whether Western society is reaching a tipping point analogous to the 1930s, with ascendant populism, nationalism, militarism and a worrying undercurrent of hate crimes and ethnic strife, Kruglanski is working to figure out how the unsaveable can become the saved.

If there is an entrance to extremism, he reasons, surely there must also be an exit.

No universal, singular combination of race, religion, family or income bracket predicts who picks up a gun or makes a bomb to further ideological goals.

Osama bin Laden, founder of al-Qaida, was the son of a billionaire businessman and educated at prestigious institutions. Dylann Roof, a white supremacist who killed nine black parishioners in a South Carolina church, dropped out of school, dabbled in drugs and couldn’t hold down a job, yet he grew up in a middle-class household and had no record of previous violence. After his family received asylum in America, Tamerlan Tsarnaev dreamed of making the U.S. Olympic boxing team before masterminding the Boston Marathon bombing.

Kruglanski’s innovation in understanding the foundation of extremism lies in jettisoning demographic diagnoses in favor of psychological signposts he calls the “three Ns”: the need, the narrative and the network. Extremism, he says, provides certain people with a sustaining sense of purpose through a quest, an enemy to fight and a community of like-minded thinkers.

“The foundation is the universal human need for significance,” he says. “Overnight, you become a hero—your kaffiyeh flying in the wind, riding in a Humvee with a big gun.”

Postdoctoral researcher Katarzyna Jaśko, Gary LaFree, director of UMD’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), and Kruglanski, a co-founder and former co-director of START, recently put this theory to the test.

In a November 2016 paper published in Political Psychology, they analyzed 1,500 ideological extremists from across the political spectrum, whose activities in the United States varied from illegal protests to bombs. They found that failure at work, romantic and social rejection, and abuse were more common among those who pursued violence. Extremists who also had nonviolent friends, or who were expelled from organizations advocating violence, were less likely to strike out.

The “big selector” in this process, Kruglanski says, is what narrative sates a person’s need for significance. What cause is he or she willing to fight and die for in the quest? Is it a fight for civil rights or for ethnic or religious supremacy? A terrible result isn’t preordained, he says, suggesting that Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi could be considered “extremists” as well, as their level of self-sacrifice was rare and beyond what most people would be prepared to do.

“It can be channeled to being a Peace Corps volunteer or a great humanist if these are the values that are ingrained in you, that are supported by your group,” he says. “Or it can be joining an extremist organization.”

LaFree says Kruglanski has been a “pioneer” in applying such psychological theories to political violence.

“The individuals involved in terrorist attacks are often different than criminals,” LaFree says. “They could have gone in another direction.”

The psychological needs of extremists, however, are unlikely to be satisfied by a regular paycheck.

“These people have to have hope of a meaningful, significance-lending existence,” Kruglanski says, “if they aren’t going to be vulnerable to these extremist ideas.”

Kruglanski led a team that studied the effectiveness of rehabilitation on the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), who fought to create an independent ethnic state in Sri Lanka, surrendered to the military and, in 2009, were arrested and jailed. The researchers found that a holistic menu of vocational, cultural and psychological education, along with extracurricular activities such as sports, led to a notable decline in the former terrorists’ support for the LTTE, Tamil independence and armed struggle, in addition to less narcissism and a reduced preference for quick decision-making.

Kruglanski led a team that studied the effectiveness of rehabilitation on the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), who fought to create an independent ethnic state in Sri Lanka, surrendered to the military and, in 2009, were arrested and jailed. The researchers found that a holistic menu of vocational, cultural and psychological education, along with extracurricular activities such as sports, led to a notable decline in the former terrorists’ support for the LTTE, Tamil independence and armed struggle, in addition to less narcissism and a reduced preference for quick decision-making.

Leaving an extremist movement is like recovering from drug addiction, Kruglanski says. One of his forthcoming book projects focuses on former neo-Nazis in Germany, and he found them extremely vulnerable as they reckoned with the absence of clear-cut meaning and support.

Channeling—rather than extinguishing—the search for meaning might be the needed method.

“The best way to keep them excited and from sliding back is to engage them in an idealistic endeavor,” he says.

Robert Örell, a friend of Kruglanski, agrees. Growing up in Stockholm, Örell struggled with poor eyesight, subsequent academic problems and conflicts with suburban gangs. By the time he was 14, white supremacy groups had helped ground him with clothes, ideas, style and attitude.

“We were so right. We were such a strong team,” he says. “Instead of focusing on being a failure, I could focus on being someone they were afraid of.”

Compulsory military service, however, gave Örell some distance from his compatriots and self-esteem from being a good soldier. Today, he directs EXIT Sweden, an organization helping neo-Nazis and other extremists leave their movements, which he described as “an apocalyptic battle for good and evil.”

“There is a great emptiness (after leaving),” Örell says. “Where do you put your engagement and interest?”

Watch Professor Ari Kruglanski talk to The New York Times about his theory of cognitive closure—people’s desire for black-and-white answers in a world full of grays.

As the Soviet army approached Łódź in January 1945, there were no more lists left to save lives.

The Nazis had dug nine large ditches in a nearby cemetery in preparation to massacre the Jewish work crews that lingered in the ghetto. But encouraged by news broadcast over contraband radios and booming Russian artillery getting ever closer, the several hundred souls still inside refused to come out.

Before the first Soviet tank entered the city on Jan. 19, Kruglanski, then 5, spent two weeks huddled with his mother, father, grandmother, uncle and aunt in a windowless room, accessed by a cupboard; his father sneaked out at night to scavenge for food.

Before the first Soviet tank entered the city on Jan. 19, Kruglanski, then 5, spent two weeks huddled with his mother, father, grandmother, uncle and aunt in a windowless room, accessed by a cupboard; his father sneaked out at night to scavenge for food.

“I knew that there was danger,” he says. “I remember that, the fear of being caught.”

The conclusion of World War II, however, didn’t end the family’s troubles. The communist regime in Poland made life difficult for Kruglanski’s father, a textile engineer who was slurred as a capitalist. In 1950, the family immigrated to the newly independent state of Israel.

After high school, Kruglanski served four years in the Israeli air force working on radar, then went to the University of Toronto to study architecture. Despite liking math and drawing, he didn’t think he had the necessary design talent and was drawn to psychology. After just two years at the University of California, Los Angeles—“I was a young man in a hurry,” he says—Kruglanski earned his Ph.D. in 1968. He has been at UMD since 1987.

After high school, Kruglanski served four years in the Israeli air force working on radar, then went to the University of Toronto to study architecture. Despite liking math and drawing, he didn’t think he had the necessary design talent and was drawn to psychology. After just two years at the University of California, Los Angeles—“I was a young man in a hurry,” he says—Kruglanski earned his Ph.D. in 1968. He has been at UMD since 1987.

His academic career, centered on motivation and judgment, has been marked by research that defied conventional wisdom. In 1975, Kruglanski theorized that the distinction between external and internal motivation was artificial, since we don’t automatically follow outside commands without some individual deliberation. (“You are not a robot,” he says.)

Kruglanski tapped a wellspring of controversy with a 2003 article that reviewed studies of left- and right-wing thinking and found that conservative opinions correlate with traits such as a fear of death, intolerance of ambiguity and sensing threats. High-profile commentators such as Ann Coulter and George Will charged that Kruglanski was positing conservatism as a mental illness, even though the research found that closed-mindedness or threat sensitivity can be beneficial, by heightening awareness and shutting out bad information. And on the other hand, liberal tendencies can lead to disorganization and indecisiveness.

“He’s really courageous. That’s very inspiring as a scientist,” says Michelle Gelfand, a UMD psychology professor, start researcher and frequent collaborator with Kruglanski. “He is really just a visionary about theory.”

His work from the late 1980s is undergoing a mass media revival today. Kruglanski coined the term “cognitive closure” back then to describe the human need for definitive answers. It manifests itself in everyday choices like what to eat and what to wear but can also spur more radical and detrimental behavior. Kruglanski developed a scale to measure it, asking subjects to rate agreement on everything from “I hate to change my plans at the last minute” to “I feel that there is no such thing as an honest mistake.”

Kruglanski has been quoted on cognitive closure in The Atlantic, “PBS NewsHour” and The New York Times in recent months. As someone who believes psychologists have an obligation to offer expertise on current events, he’s found plenty to talk about.

In February, Kruglanski traveled to Dubai to give a presentation at the World Government Summit, an annual conference that attracts leaders from academia, Silicon Valley and institutions like the World Bank. He was struck by how others’ speeches broadly fell into two camps: one, that we are on the cusp of a technological paradise; the other, that we are revisiting the devastating 1930s.

Nearly a decade after the Great Recession, income inequality has widened and large parts of the world lack sustainable economic opportunities. Wars in the Middle East have driven a flood of refugees into Europe, releasing xenophobia once thought to be on society’s margins.

Borne along by currents of isolationism and populism, countries such as Poland and Hungary have embraced authoritarian leadership, and far-right parties have gained popularity and influence in France and the Netherlands. The British vote to leave the European Union and the U.S. presidential election of Donald Trump razed the presumed international consensus around open markets and open borders.

“We allowed ourselves to accept the politics of inevitability, the sense that history could move in only one direction: toward liberal democracy,” historian Timothy Snyder wrote in his recent book, “On Tyranny: Lessons from the Twentieth Century.” “In doing so, we lowered our defenses, constrained our imagination and opened the way for precisely the kinds of regimes we told ourselves could never return.”

“We allowed ourselves to accept the politics of inevitability, the sense that history could move in only one direction: toward liberal democracy,” historian Timothy Snyder wrote in his recent book, “On Tyranny: Lessons from the Twentieth Century.” “In doing so, we lowered our defenses, constrained our imagination and opened the way for precisely the kinds of regimes we told ourselves could never return.”

This chain of events fits neatly into Kruglanski’s work on cognitive closure and extremism—namely, the human tendency to gravitate to black-and-white answers, even if they involve violence.

“When uncertainty becomes excessive and adverse, people feel confused and lacking guidance for action,” he says. “It is those moments that are exploited by extremist leaders that promise certainty, that promise to alleviate ambiguity and create the world that will be satisfactory and predictable and replete with good news.”

In the United States, organizations such as the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) are sounding the alarm about a resurgent radical right. The SPLC's annual report, “The Year in Hate and Extremism,” described a sharp increase last year in anti-Muslim hate groups and heightened enthusiasm among neo-Nazi publications and racist organizations that interpret the presidential election as an explicit backing of white nationalism.

The SPLC collected nearly 1,400 bias-related harassment and intimidation incidents between the election and Feb. 7, including vandalized Jewish cemeteries and torched mosques. In February and March, Indian men in Kansas and Seattle were shot in alleged hate crimes, and police said a white Army veteran from Baltimore, who stabbed and killed an African-American man in New York City, was motivated by hostility to interracial relationships.

White supremacist flyers were tacked to UMD buildings on multiple occasions since December and investigated by university police as hate bias incidents, with President Wallace Loh calling the posters “an affront to who we are and what we stand for.” Colleges in the D.C. area and across the nation found similar recruitment signs posted by white power groups such as Vanguard America and Identity Evropa.

Loneliness, isolation and a feeling of superfluousness, political theorist Hannah Arendt wrote, are the “common ground for terror.” Finding new ways to give people meaning, Kruglanski says—positive, durable and significant meaning—will be critical to avoiding catastrophe.

“How do you prepare a new generation for this accelerated globalism, this accelerated technological development, so that billions will not be left feeling undignified?” he asks.

The answer, Kruglanski says, will not be found if we isolate ourselves. After all, the walls built today to keep people out may be used tomorrow to keep people in.

TERP

Photos courtesy of Arie W. Kruglanski and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

What do you think of Terp magazine? Take our short survey at terp.umd.edu and be entered to win a Maryland sweatshirt.

Tags

Research