- May 12, 2015

- By Chris Carroll

There was usually a warning one day in advance, when Carol Murphy would feel a chill she couldn’t shake—a “bone cold,” she says—in her feet and lower legs.

Next came the sparkly visual distortions known as aura, a light show of misfiring neurons in her brain. When that stopped, the pain of the migraine descended—crushing, constant and seemingly endless, stretching out for days.

Over the years, Murphy, of Fairborn, Ohio, tried every migraine drug and therapy she could, but often they made her feel worse.

“It was 15, 16, 17 days a month I would be at half-mast, but I was raising three children,” she says. “You can’t just go to bed.”

As she got older, the pain grew stronger. Approaching age 60, the cutoff for the drug trials she was participating in, she saw an article about an experimental drug-free migraine treatment. In late 2005, researchers at Ohio State University handed her a curious device the size of a large book to take home. Known as a transcranial magnetic stimulator (TMS), the device sends magnetic pulses into the brain in hopes of stopping migraines.

“I had an aura, so I held it up to my head and pulsed it, and the aura sort of stopped,” she says. “About an hour later, the aura came back, so I pulsed it again.”

When the aura finally halted, the pain should have hit. Except it didn’t.

“It was, whoa, there’s no pain,” she says. “It was immediate. It was amazing.”

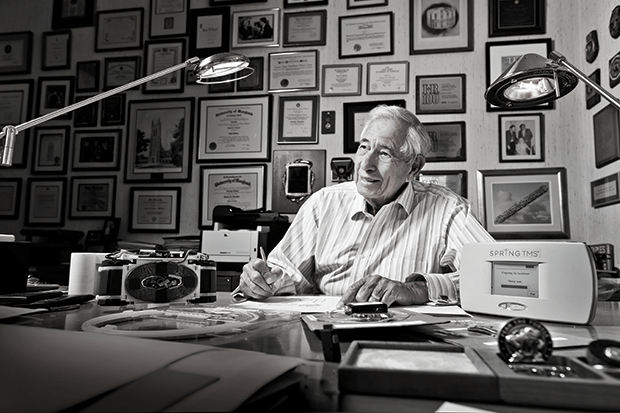

Amazing, but maybe not surprising, given the source. The headache device, which received final approval from the Food and Drug Administration last year, is the brainchild of one of the great biomedical inventors of the past century, Robert E. Fischell M.S. ’54, Sc.D. (honorary) ’96.

His drive to devise solutions to nagging problems has resulted in more than 200 patents and a bewildering array of medical developments, including rechargeable pacemakers, the first implantable insulin pump and modern coronary stents.

Now Fischell, 86, has one of the biggest, most intractable problems of all squarely in his sights: physical pain.

No, he’s not going after the kind that warns us to move our hands away from hot burners or skip that last heavy set in the weight room. Instead, he wants to end the chronic pain that the Institute of Medicine says causes suffering for more than 100 million Americans like Carol Murphy.

“We have a way to eliminate pain without drugs and with zero side effects,” he says. “The opportunity to help people is tremendous.”

FLEETING BURSTS OF ELECTROMAGNETISM known as pulses create electrical current in body tissues, blocking pain. That’s the concept behind the headache device, which he patented in 2002 along with his oldest son, David, and Canadian neurologist Dr. Adrian Upton.

UMD researchers helped develop prototypes of the device being brought to market by the Baltimore-based company eNeura. It is now delivering the device, called SpringTMS, to headache clinics around the nation in preparation for broader distribution in the next year.

How do electromagnetic pulses kill pain? Strangely enough, science can’t precisely answer that question because of our limited knowledge of the brain and nervous system. But Fischell’s theory is that the magnetic field scrambles communication between nerve cells. The result, he says, is that the signals received by the brain no longer register as pain.

Magnetic pulses have been used to treat depression, and implantable electrodes that direct electrical currents through the back for spinal pain work on a similar principle—although that requires expensive surgery and carries all of its associated risks, Fischell points out.

David Rosen, CEO of eNeura, predicts SpringTMS will revolutionize migraine treatment, but clinicians may at first be wary.

“Doctors, neurologists and headache specialists have spent virtually their entire careers treating migraines only with drugs,” Rosen says. “What we’re doing is really disruptive to the market.”

The only published efficacy study of the device showed that it works. The 267 migraine sufferers who participated had far better results using TMS than with a placebo treatment. A safety study, meanwhile, showed no harmful effects.

After the studies were released, though, the California Technology Assessment Forum dismissed the device for working no better than a common class of migraine drugs called triptans, while costing more.

But that trial was done using only a few magnetic pulses, Rosen says. Ongoing studies in Britain, where the devices are used in clinics, suggest more pulses work better. And even if SpringTMS is only as effective as triptans, it still wins, he argues.

“Which would you choose if you had your choice between two equally effective treatments, but one has no side effects and you didn’t have to ingest something?” he says.

Once the devices are introduced broadly, Rosen says, the company plans to rent them for home use, aiming to price them about the same as popular migraine drugs.

“We want people to be able to afford to use it,” he says.

AS HIS MIGRAINE DEVICE COMES TO MARKET, Fischell is pushing the technology in new directions. If pulsed electromagnetic pain relief works on the head, he wonders, why not on other parts of the body?

We’ll soon find out if he’s right. Researchers with the Fischell Department of Bioengineering, which Fischell and his family founded with a $31 million donation in 2005 (the largest gift in UMD history at the time), as well as with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, are working on a new device. It has a roughly 50 percent stronger magnetic field than the cordless SpringTMS. Because it plugs into a wall socket, it also provides a series of zaps more rapidly.

In a windowless lab in A.V. Williams Hall strewn with bits of circuit board and esoteric-looking components, Wesley Lawson, professor of electrical and computer engineering, has devised a working prototype of the device, and students are painstakingly building 12 copies.

The machines will be tested on back, shoulder, knee and foot pain, and could be effective elsewhere, Fischell says.

Once the devices are ready, a small clinical trial targeting lower back pain will begin at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, overseen by Dr. Peter Rock, chair of the anesthesiology department.

“Certainly if this works, it’s not going to be a treatment for all types of pain, but there is a significant number of people who would benefit if it does,” Rock says. “And any ability to make a dent in opioid use would be worthwhile.”

Fischell is confident of his device’s success. His ability to invent, he says, is an instinctive method of quickly grasping a problem and producing a solution—sometimes it appears in his mind’s eye as an engineering drawing. He thinks he’s done just that with his campaign against physical pain.

Fischell is planning a network of U.S. clinics where people suffering from bad backs, nerve pain from chemotherapy, achy arthritic joints and a host of other maladies can seek affordable, drug-free palliative care. Along with business partners—including UMD and the School of Medicine, each with a 3 percent cut—he’s set up a company called Zygood LLC to lay the groundwork for the clinics, which he hopes will operate nationwide and bring comfort to millions.

Fischell is planning a network of U.S. clinics where people suffering from bad backs, nerve pain from chemotherapy, achy arthritic joints and a host of other maladies can seek affordable, drug-free palliative care. Along with business partners—including UMD and the School of Medicine, each with a 3 percent cut—he’s set up a company called Zygood LLC to lay the groundwork for the clinics, which he hopes will operate nationwide and bring comfort to millions.

“I’m going to devote my life to this new pain effort,” he says.

IN 2006, NINE MONTHS AFTER CAROL MURPHY got the prototype of Fischell’s migraine device—allowing her what she considered a normal life for the first time in years—the Ohio State researchers took it back and ended that part of the study.

Her pain immediately returned. She turned again to drug treatments, even having Botox injected into her head and neck, and steroids injected into her spine.

All the while, she waited for the device to reach the market. Frustrated by the delay, she agreed to testify before Congress in 2011 on speeding up the development of medical devices. There, she met Fischell, who had one of his migraine machines in tow. She looked at it longingly.

“I want to steal that from you,” she said.

Fischell chuckled and later provided Murphy with a phone number to a doctor in Britain, where the device had already been approved. She spent thousands to fly there and receive Fischell’s device on prescription, and since 2011 has been nearly migraine-free.

Her 38-year-old daughter, Cassie, is beginning to experience worsening migraines.

“I see her following in my footsteps and it scares me,” she says. “I would love for her to be able to get this soon.” TERP

Tags

Research